Key Takeaways

- The topics to which this book is devoted have to do with the ordinary conduct of life. They pertain, in one way or another, to a question that is both ultimate and preliminary: how should a person live?

- Our response to it bears directly and pervasively upon how we conduct ourselves—or, at least, upon how we propose to do so. Perhaps even more significantly, it affects how we experience our lives. When we seek to understand the world of nature, we do so at least partly in the hope that this will enable us to live within it more comfortably. To the extent that we know our way around our environment, we feel more at home in the world. In our attempts to settle questions concerning how to live, on the other hand, what we are hoping for is the more intimate comfort of feeling at home with ourselves.

- In certain cases, moreover, what moves us is an especially notable variant of caring: namely, love. In proposing to expand the repertoire upon which the theory of practical reason relies, these are the additional concepts that I have in mind: what we care about, what is important to us, and what we love.

- Caring about something differs not only from wanting it, and from wanting it more than other things. It differs also from taking it to be intrinsically valuable.

- When a person cares about something, on the other hand, he is willingly committed to his desire.

- Regardless of how suitable or unsuitable the various things we care about may be, caring about something is essential to our being creatures of the kind that human beings are.

- Suppose now that someone is performing an action that he wants to perform; and suppose further that his motive in performing this action is a motive by which he truly wants to be motivated.

- Under these conditions, I believe, the person is enjoying as much freedom as it is reasonable for us to desire. Indeed, it seems to me that he is enjoying as much freedom as it is possible for us to conceive. This is as close to freedom of the will as finite beings, who do not create themselves, can intelligibly hope to come.

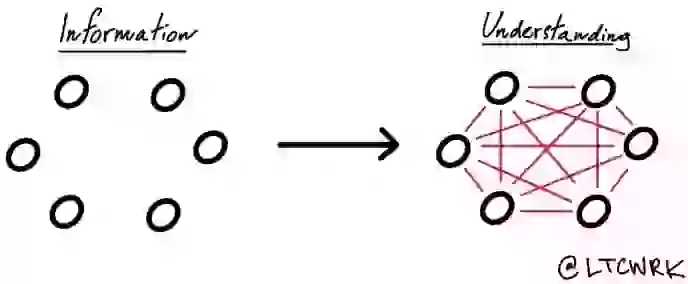

- is by caring about things that we infuse the world with importance. This provides us with stable ambitions and concerns; it marks our interests and our goals. The importance that our caring creates for us defines the framework of standards and aims in terms of which we endeavor to conduct our lives. A person who cares about something is guided, as his attitudes and his actions are shaped, by his continuing interest in it. Insofar as he does care about certain things, this determines how he thinks it important for him to conduct his life.

- But identifying the criteria to be employed in evaluating various ways of living is also tantamount to providing an answer to the question of how to live, for the answer to this question is simply that one should live in the way that best satisfies whatever criteria are to be employed for evaluating lives.

- This means that the most basic and essential question for a person to raise concerning the conduct of his life cannot be the normative question of how he should live. That question can sensibly be asked only on the basis of a prior answer to the factual question of what he actually does care about. If he cares about nothing, he cannot even begin to inquire methodically into how he should live; for his caring about nothing entails that there is nothing that can count with him as a reason in favor of living in one way rather than in another. In that case, to be sure, the fact that he is unable to determine how he should live may not cause him any distress. After all, if there really is nothing that he considers important to him, he will not consider that to be important to him either.

- Loving someone or something essentially means or consists in, among other things, taking its interests as reasons for acting to serve those interests. Love is itself, for the lover, a source of reasons. It creates the reasons by which his acts of loving concern and devotion are inspired.

- This relationship between love and the value of the beloved—namely, that love is not necessarily grounded in the value of the beloved but does necessarily make the beloved valuable to the lover—holds not only for parental love but quite generally.4 Most profoundly, perhaps, it is love that accounts for the value to us of life itself.

- When we love something, however, we go further. We care about it not as merely a means, but as an end. It is in the nature of loving that we consider its objects to be valuable in themselves and to be important to us for their own sakes.

- Finally, it is a necessary feature of love that it is not under our direct and immediate voluntary control.

- What people cannot help caring about, on the other hand, is not mandated by logic. It is not primarily a constraint upon belief. It is a volitional necessity, which consists essentially in a limitation of the will. There are certain things that people cannot do, despite possessing the relevant natural capacities or skills, because they cannot muster the will to do them. Loving is circumscribed by a necessity of that kind: what we love and what we fail to love is not up to us.

- Love is the originating source of terminal value. If we loved nothing, then nothing would possess for us any definitive and inherent worth. There would be nothing that we found ourselves in any way constrained to accept as a final end.

- Logic and love preempt the guidance of our cognitive and volitional activity.

- It may seem, then, that the way in which the necessities of reason and of love liberate us is by freeing us from ourselves. That is, in a sense, what they do. The idea is nothing new. The possibility that a person may be liberated through submitting to constraints that are beyond his immediate voluntary control is among the most ancient and persistent themes of our moral and religious traditions.

- Aristotle apparently believed that there must be a single final end at which everything we do aims. I mean to endorse only the more modest view that each of the things we do must aim at some final end.

- Without such purpose, action cannot be satisfying; it is inevitably, as Aristotle says, “empty and vain.” By providing us with final ends, which we value for their own sakes and to which our commitment is not merely voluntary, love saves us both from being inconclusively arbitrary and from squandering our lives in vacuous activity that is fundamentally pointless because, having no definitive goal, it aims at nothing that we really want. Love makes it possible, in other words, for us to engage wholeheartedly in activity that is meaningful. Insofar as self-love is tantamount just to a desire to love, it is simply a desire to be able to count on having meaning in our lives.

- Being wholehearted means having a will that is undivided. The wholehearted person is fully settled as to what he wants, and what he cares about. With regard to any conflict of dispositions or inclinations within himself, he has no doubts or reservations as to where he stands.

- This wholehearted identification means that there is no ambivalence in his attitude toward himself. There is no part of him—that is, no part with which he identifies—that resists his loving what he loves. There is no equivocation in his devotion to his beloved. Since he cares wholeheartedly about the things that are important to him, he can properly be said to be wholehearted in caring about himself.

What I got out of it

- The only way we can truly feel fully fulfilled in life is by pursuing our goals and passions to the greatest extent and with all we have. And the only way this happens is with love, not only for others but for ourselves as well.