Key Takeaways

- Sorensen gained Henry Ford’s respect by translating Ford’s design concepts into wooden parts that could be seen and studied. Advancing rapidly, he was second in command of Piquette production by 1907….Sorensen’s “crowning achievement,” Ford historian Ford R. Bryan wrote in 1993, was the “design of the production layout of the mammoth Willow Run Bomber Plant.” Others have cited as Sorensen’s greatest accomplishment his role in the development of mass production….Six years before we installed it, I experimented with the moving final assembly line which is now the crowning touch of American mass production. Before the eyes of Henry Ford, I worked out on a blackboard the figures that became the basis for his $5 day and the overwhelming proof of the present economic truism that high wages beget lower-priced mass consumption.

- During the nearly forty years I worked for Henry Ford, we never had a quarrel. If we disagreed on policy, or anything else, a quiet discussion settled things. I don’t recall ever receiving a direct order, “I want this done” or “Do it this way.” He got what he wanted by hint or suggestion. He seldom made decisions—in fact, when I brought a matter up for his approval, his usual reply was, “What are we waiting for? Go ahead!”

- I believe there are three main reasons for my long tenure. One advantage I had over others was that, from my pattern-making days on, I could sense Henry Ford’s ideas and develop them. I didn’t try to change them. This was not subservience. We were pioneering; we didn’t know whether a thing was workable until we tried it. So, Mr. Ford never caught me saying that an idea he had couldn’t be done. If I had the least idea it couldn’t, I always knew that the thing would prove or disprove itself. When designers were given Mr. Ford’s ideas to execute, the usual result was incorporation of some of their ideas, too. But it was part of my patternmaking training to follow through with what was given me. I suppose that was why Mr. Ford turned to me. Another reason for my long tenure was that I minded my own business. Production—whether it was automobiles, tractors, aviation motors, or B-24 bombers—its planning, installation and supervision was a seven-days-a-week job. I had no time for the outside interests of Henry Ford which arose as he grew older. Labor matters were not in my province. I took no part in his crusades like the World War I Peace Ship to “get the boys out of the trenches by Christmas.” I was not involved in his miscast and fortunately unsuccessful candidacy for United States senator. I did not share his racial prejudices or his diet fads, except that by preference I am a teetotaler and nonsmoker. I might scour the country for automobile parts but not for antiques for Greenfield Village. He gave up trying to make a square dancer out of me. By sticking to my job of production and not mixing in outside affairs, the white light of publicity fortunately did not beat down upon me until World War II, when I had been with Mr. Ford for more than thirty-five years. I avoided headlines by preference.

- He was unorthodox in thought but puritanical in personal conduct. He had a restless mind but was capable of prolonged, concentrated work. He hated indolence but had to be confronted by a challenging problem before his interest was aroused. He was contemptuous of money-making, of money-makers and profit seekers, yet he made more money and greater profits than those he despised. He defied accepted economic principles, yet he is the foremost exemplar of American free enterprise. He abhorred ostentation and display, yet he reveled in the spotlight of publicity. He was ruthless in getting his own way, yet he had a deep sense of public responsibility. He demanded efficient production, yet made place in his plant for the physically handicapped, reformed criminals, and human misfits in the American industrial system. He couldn’t read a blueprint, yet had greater mechanical ability than those who could. He would have gone nowhere without his associates, we did the work while he took the bows, yet none of us would have gone far without him. He has been described as complex, contradictory, a dreamer, a grown-up boy, an intuitive genius, a dictator, yet essentially he was a very simple man.

- In engineering work in the drafting room, it was plain to the men to whom he gave his work that he could not make a sketch or read a blueprint. It was to his everlasting credit that, with his limited formal education, his mind worked like a modern electronic calculating machine and he had the answer to what he wanted. The trick was to fathom the device or machine part that was on his mind and make the object for him to look at. That was where I came in.

- Henry Ford was no mystic or genius. He was a responsible person with determination to do his work as he believed it should be done. This sense of responsibility was one of his strongest traits.

- This ability to sense signs of the times and to counteract forces that showed danger signals was almost uncanny. I would go to him with problems that looked insurmountable. Nothing appeared to frighten him….There is no doubt that Henry Ford had courage. Probably he will never be glorified for his Peace Ship excursion; but no one can tell me it didn’t take courage to undertake it. It took courage, too, to fight the Selden patent, to hold to his fixed idea of a cheap car, to battle dividend-hungry boards of directors, to build River Rouge plant in the face of stock-holder opposition.

- It parallels in a small way, but is only partially accountable for, his long-time habit of stirring up associates to see their reactions under stress. His lasting accomplishments were achieved when facing down opposition, such as when his directors opposed the Model T idea…Constant ferment—keep things stirred up and other people guessing—was the elder Ford’s working formula for progress.

- Henry Ford’s greatest failure was in expecting Edsel to be like him. Edsel’s greatest victory, despite all obstacles, was in being himself.

- He could not make a speech. His few attempts to talk to a group of people were pitiful.

- With the obvious exception of his single-purpose goal of a cheap car for the masses, a set policy was next to impossible with him. It was impossible because by nature he was an experimenter.

- When he wanted to size up a man quickly he loaded him with power. If the man took the least advantage of his new position he got some kind of warning, not from Henry Ford but from the least expected quarter. How he accepted the warning was what Henry Ford was watching. If he went to Ford to see if the warning was really coming from him, he would be encouraged to disregard everything. That would throw him off completely, but in a few days he was out, completely mystified over what had really happened.

- I learned not to take advantage of Mr. Ford or of his generosity. I could sense what he wanted and I did not need to be told what to do.

- Henry Ford was opinionated in matters about which he knew little or nothing. He could be small-minded, suspicious, jealous, and occasionally malicious and lacking in sincerity. He probably hastened the death of his only son.

- He came close to wrecking the great organization he had built up. These were his defects. Taken by themselves, they were grave faults, and it might well be wondered how one could retain one’s self-respect and still serve such a man. But when weighed against his good qualities, his sense of responsibility, his exemplary personal life, and his far-reaching accomplishments, these defects become microscopic. It is not for his failings but for his impact upon his time and his momentous part in liberating men from backbreaking toil that he will stand out in the future…It was destined to make motor transport universal, to attain mass production, to demonstrate the superiority of an economy of abundance over one of scarcity, and to begin the elevation of a standard of living to a height never before dreamed of.

- Ford was not an expert, and he didn’t rely upon experts, whether they were scientists, engineers, railroad men, economists, educators, business executives, or bankers. He was an individualist who arrived at conclusions—both right and wrong—by independent thought.

- One is rigid system, in which rules tend to be paramount; the other is flexible method, in which the objective comes first.

- We trained thousands of mechanics that way. When foremen or executive supervisors were needed, they were picked from men who showed ability in operating machines. This was a fundamental principle during the first three periods of Ford Motor Company. Good managers at Ford had to have some of these qualities: (i) Refreshing simplicity. (2) Brains. (3) Education. (4) Special technical ability. (5) Tact. (6) Energy and Grit. (7) Honesty. (8) Judgment. (9) Common sense. (10) Good health.

- In today’s industrial organizations a situation rather than the personality is the dominant factor. The situation controls, and the true leader is the one who responds immediately and effectively to the situation. And, since a situation is always primary, authority derives from function rather than position. The responsibility is for and not to.

- Too often the concern of corporation executives about their titles—even size and furnishings of their offices—deflects thought and energy from jobs they are supposed to do. That concern may whet ambition—but with a wrong emphasis. In the absence of a flock of titles, such things didn’t worry us at Ford.

- Selection is too narrow a word when thinking of building for leadership. Inside any company, some of the ablest men are never selected. They just get a job in the old-fashioned way and emerge on merit. A smart boss watches for them and does something about it as soon as they emerge. Some may have formal education but many do not. It is still the glory of our country that this doesn’t matter. A man is doomed not by being uneducated but by remaining so. Who can tell us what leadership is? It is a radiant quality which some men possess which makes others swing joyously into common action. What they do is wisely conceived and eminently fair. Such leadership, which is above all the characteristic of American production and the function of voluntary effort, springs from mutual understanding. The boss must know the worker and the worker must know the boss. They must respect each other.

- Ford knew when to give praise when it was due and when to make fair criticism when that was due. These are two of the strongest attributes of wise leadership, particularly when dealing with the imaginative and creative personalities so much needed in industry.

- It isn’t the incompetent who destroy an organization. The incompetent never get into a position to destroy it. It is those who have achieved something and want to rest upon their achievements who are forever clogging things up. To keep an industry thoroughly alive, it should be kept in perpetual ferment.

- When one man began to fancy himself an expert, we had to get rid of him. The minute a man thinks himself an expert he gets an expert’s state of mind, and too many things become impossible. The Ford operations and creative work were directed by men who had no previous knowledge of the subject. They did not have a chance to get on really familiar terms with the impossible.

- Proved competence in some field plus intellectual curiosity and audacity are to me essential qualities. The trick is to detect them.

- As time went on, Wills specialized less in development work and more in metallurgy and tool design.

- It was the great common sense that Mr. Ford could apply to new ideas and his ability to simplify seemingly complicated problems that made him the pioneer he was.

- To get everything simple took a lot of fussy work.

- Many of the world’s greatest mechanical discoveries were accidents in the course of other experimentation. Not so Model T, which ushered in the motor transport age and set off a chain reaction of machine production now known as automation. All of our experimentation at Ford in the early days was toward a fixed and, then, wildly fantastic goal.

- It was because of our constant tinkering that we were so right in many of the things we made.

- Today, we do not hear so much about “mass production” as we do about “automation.” Both evolve from the same principle: machine-produced interchangeable parts and orderly flow of those parts first to subassembly, then to final assembly. The chief difference is that mechanized assembly is more complete in automation; where men once tended machine tools, the job is now done electronically, with men, fewer of them, keeping watch over the electronics.

- Next, he required each bidder to submit prices based on material, labor, and other overhead, and even the amount of profit. Under such a system there was no question about costs being kept down, and the savings were tremendous. Instead of being resented, Diehl was very much respected by suppliers, for although their prices were kept in line they were assured of profit.

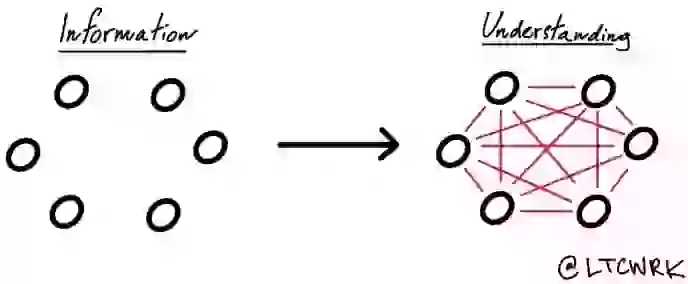

- Henry Ford had no ideas on mass production. He wanted to build a lot of autos. He was determined but, like everyone else at that time, he didn’t know how. In later years he was glorified as the originator of the mass production idea. Far from it; he just grew into it, like the rest of us. The essential tools and the final assembly line with its many integrated feeders resulted from an organization which was continually experimenting and improvising to get better production…Today historians describe the part the Ford car played in the development of that era and in transforming American life. We see that now. But we didn’t see it then; we weren’t as smart as we have been credited with being. All that we were trying to do was to develop the Ford car. The achievement came first. Then came logical expression of its principles and philosophy. Not until 1922 could Henry Ford explain it cogently: “Every piece of work in the shop moves; it may move on hooks on overhead chains going to assembly in the exact order in which the parts are required; it may travel on a moving platform, or it may go by gravity, but the point is that there is no lifting or trucking of anything other than materials.” It has been said that this system has taken skill out of work. The answer is that by putting higher skill into planning, management, and tool building it is possible for skill to be enjoyed by the many who are not skilled.

- Machines do not eliminate jobs; they only make them easier—and create new ones.

- The Ford Model T was built so that every man could run it. Ford mass production made it available to everyone. Ford wages enabled everyone to afford it. The Ford $5 day rejected the old theory that labor, like other commodities, must be bought in the cheapest market. It recognized that mass producers are also mass consumers, that they cannot consume unless they are able to buy.

- Ever since it was founded, Ford Motor Company had shared some of its prosperity with its people. Employees who had been with the company for three years or longer received 10 per cent of their annual pay, and efficiency bonus checks were handed to executives and branch managers….It was just good, sound business. As Henry Ford said at the time, it was not “charity” but “profit sharing and efficiency engineering.”

- Five years later, when the minimum wage had been increased to $6 a day, we knew that our establishment of the $5 minimum for an eight-hour day was one of the best cost-cutting moves we had ever made.

- With them, profits came first and set the price accordingly. Ford held that if the price is right the cost will take care of itself. Price first, then cost, was a paradox. It ran counter to prevailing business practice, but Ford made it work.

- During World War I, Mr. Ford was contemplating a reduction of $80 a car. Since the company was turning out 500,000 cars a year, it was argued that this would reduce the company’s income by $40,000,000. This calculation had nothing to do with the matter. What was entirely overlooked was the fact, as brought out in the $ 5-day calculations, that the $80 reduction would sell more than 500,000 cars and that the savings from the lower costs of greater production would more than absorb the price cut.

- No matter how efficient that manufacturing, coal and iron costs are prime elements in determining the cost of the completed automobile. These fluctuation costs are beyond the control of other auto companies. When Ford built the River Rouge plant he either owned or had lined up enough coal and iron deposits to handle his production. Thus, he controlled sources of his two most important materials.

- As a result, Ford Motor Company emerged from World War II to peacetime manufacture of automobiles with five great advantages over its competitors: First, as we have seen, it had its own source of raw materials. Second, it had the world’s greatest, most complete industrial manufacturing plant—the biggest machine shop on earth. Third, the Rouge plant, with assets of $1,500,000,000, was owned outright and was built out of profits and not a cent of borrowed money. Fourth, it had a work force and supervision at the foreman level trained in Ford production methods. Fifth, it had its own steel mill and therefore was unaffected by a steel shortage after the war which crippled the operations of many less fortunate companies. True, its postwar top management was new, but given those five incalculable advantages, how could it fail?

- When something new and different is sought, it is useless to copy; start fresh on a new idea. This means fresh minds at work.

- These stockholders had originally put up $33,100. Sixteen years later they sold out for more than $105,000,000. Also, in those sixteen years, their total dividends were more than $30,000,000.

- The skill in manufacturing the finished article was reflected in the planning. Casual visitors looking at parts being made would be astonished to see how simple it was to make a crankshaft. What they did not see was the time and experience involved in designing and in the organization that was responsible for it.

- These superintendents and their assistants were not of the sitdown type. I did not permit the top men to hold down a chair in an office. My formula for them was “You’ve got to get around.” In addition to watching work progress, I insisted that they keep their plants clean. I insisted upon spotlessness and kept an ever-watchful eye on conveniences and facilities that would lighten men’s work loads.

- We automobile men didn’t want to run a railroad, but we were driven to it because this appeared the best solution to a vexing problem. By 1920, Ford was producing a million cars a year—more than the railroads could swiftly deliver. The bottleneck was freight shipments…With motor transport on the increase and threatening their revenues, railways had little incentive to help auto manufacturers.

- It was apparent that, while the Russians had stolen the Fordson tractor design, they did not have any of our specifications for the material that entered into the various parts. And you can’t find that out merely by pulling the machine apart and studying the pieces…But ever since that day I never felt particular concern about the Russian competition in the Ford product field.

- Mr. Ford’s remark to me back in 1912, “Give them any color they want so long as it is black,” epitomized the reasons for Model T’s success and its ultimate decline.

- I had been telling him that with his new venture he might control or dominate the motorcar business. We had 50 percent of it in 1924. His reply to control was “Charlie, I don’t want all the business. Twenty-five percent will satisfy me.” Of course, to me that looked like coasting along, but it gave me a hint of why he was not in a hurry to start up; he could get all the business he wanted.

- It was not until I pointed out that we might set new standards in building them that I secured Henry Ford’s consent to make 4,000 Pratt & Whitney engines.

- First, break the plane’s design into essential units and make a separate production layout for each unit. Next, build as many units as are required, then deliver each unit in its proper sequence to the assembly line to make one whole unit—a finished plane.

- “Unless you see a thing, you cannot simplify it. And unless you can simplify it, it’s a good sign you can’t make it.”

- It had always been our policy at Ford for everyone to start at the bottom. Kanzler was one of the few exceptions and largely for that reason, I think, Mr. Ford avoided him.

- My best friends are my critics. You say, “Why did I not develop a real successor?” Mr. Ford, like many men of his kind, never had a successor, they just can’t acknowledge that such a thing is possible. Was his son even a possible successor? This war program which he, Henry Ford, never entered into, and which he would not take the slightest interest, got me in trouble plenty with him. Can’t you use your imagination a bit? I was the only authority in the Company that Washington recognized. I am the victim of that situation. I got out on my own all right rather than follow his son. That is all. Now, tell me, how could I develop an organization that would live on after I am, or he is, gone? My only ambition was to do exactly that. His grandsons, three of them, coming along, I felt I was living for them. In the bottom of my heart I still feel that way.

What I got out of it

- Really interesting to learn more about Henry Ford and the Ford empire, the good and the bad. The courage it took to take Ford to where it got and his great failure in not treating his only as his own person, driving him to illness and fracturing the relationship are worth noting. People are complex and multi-faceted, not all good nor all bad. Ford had some huge negative character flaws, but also some great ones. We should learn from him – both what to do and what to avoid.