- Background

- A parents’ main job: unconditional love, live the values you want to teach, stress hard work and education

- Ken came from humble beginnings but was taught the value of hard work from a young age and is proof of the American dream

- Always ravenous about learning – libraries on Saturdays when others were partying

- Out of army in 1963 which later saw a huge market crash. Counterintuitive at the time but he saw this as his opportunity to get his feet in the door at Wall St.

- Loving what you do is one of the greatest joys in life. I learned early how essential it was to love the work I was doing. Sometimes I look back and wonder, how did all this happen? Then the answer comes. Shit, I know how it happened: I was at a place where I was having the time of my life! I still remember what Hudson Whitenight said to me 60 years ago: “If you really love your work as much as I think you’re going to, you’re going to be a big success. So, I’m saying to a kid, I learned that ex post facto; you should learn it in front!

- Negotiating and a Win-Win Mindset

- Early in his career, Langone approached his boss about changing incentives. "Mr. Brown, I want to do something, and I’d like you to agree to it. I want to allocate a certain percentage of those commissions to the R&D department for the analysts who helped bring in this business. Mr. Brown, these guys downstairs are great; I don’t think you understand the quality of talent you’ve got down there. They’re a lot better than alright. Maybe it’s how we use them that’s not all right. But I can tell you right now, I can take these guys anyplace and do a lot of business. Rather than giving them a bonus from my end, I have another idea. Let’s you and I pick a total dollar amount off the top of whatever I bring in from Standard-Jersey, or any other company going forward, for analyst bonuses. Now, you’re going to only have to pay 70% of it because I’m going to pay 30%. I’ll tell you which analysts are higher on the approval list at Standard-New Jersey, and you can decide how much you want to allocate to each analyst. It’s completely fair. He didn’t like that so I said, “I’m going to take a portion of Unit 15’s 30% and give it to them directly. It’ll cost you nothing.” Why would you do that? he asked. “Because, Mr. Brown, when I pick up the phone and call the research department, I want those guys to jump through the phone. I want these guys to keep doing as great a job as they’ve been doing, and I want them to be excited about it…

- Capitalism is brutal, but it’s rarely a zero-sum game. Both sides of any transaction should get something out of the deal. Valeant, the pharmaceutical company, had a whole roster of important medications, but when it got caught charging obscene prices for them, its stock went down 90%. The market spoke, and Valeant had to listen. I can’t think of one deal I’ve ever done where I couldn’t have gotten more out of it than I did. As I’ve made clear, I like making money. I’m not some Buddhist monk who wants to eat beans the rest of his life. But it’s amazing what you can accomplish when you look beyond sheer profit to getting buy in by other people. I’d rather own 10% of a billion-dollar company than 100% of a $100m company. The numbers are exactly the same but by owning a piece of the billion dollar company, I get the benefit of everybody else pulling with me, and that’s a huge benefit

- One of the most important lessons in my life is this; leave more on the table for the other guy than he thinks he should get. And one of the most important rules in capitalism is incentive. I didn’t get rich by accident. I’ve always been very conscious of terms and conditions and trading, and I bargain back and forth. But I never wanted to reach a point on a deal where the other guy feels he was had. I’d rather have him feel he got me than I got him. I can live with that. If the other guy does better than I do, there’s a good chance he’ll want to come back to me and make a number of deals. On the other hand, he has to be straight with me

- The human element

- Ignore the human element in any situation at your own peril

- Everybody talks about the bottom line, but as I’ve seen time and again, you ignore the human element of business at your peril. Most of the seven deadly sins can and do come into play, and chemistry between people – good chemistry or bad – always has an effect, sometimes a huge effect: in boardrooms, in executive offices, in sales meetings. I’ve had quite a few chemistry lessons over the years.

- The only problem was that Home Depot’s great strength was (and still is) its culture, and our culture isn’t about statistics. In our culture, you don’t measure the intangible value of a sales associate saying to a customer, “Can I help you?” or, “You don’t really need that. Come over here and look at this. It doesn’t cost as much, but you’ll be fine with it.” A customer was told to buy an 89 cent screw rather than replacing his whole sink for $200. A couple months later, the guy’s wife wants a new kitchen, and she wants to go to some foo-foo kitchen showroom place. The husband says, “Oh no, I want to go see my friends at the Home Depot.” They spent $100,000 on the job. There’s nothing like these people in our stores. They’re special. Now, how do you get special people? Well, you start by treating them special. You let them know they matter. You let them know you appreciate their opinion. You let them know if they think there’s a better way of doing things than the way they’re doing them, they have an obligation to tell us, and we have an obligation to listen. You also let them know that anybody can build a big store space and put all kinds of inventory in it; the glue that holds Home Depot together are these values. We don’t just say them. We believe them, and we practice them consistently

- Management teams that rack up great numbers but ignore the human equation will eventually have a problem on their hands. In business, good numbers can be like sunlight: blindingly bright.

- Arrogance is the enemy. For many years, Bernie Marcus and I never, ever went into a Home Depot store – never once – unless we were pushing carts in from the parking lot. I sued to pray I would see a piece of trash on the floor so I could pick it up. Why? Those are entry-level tasks for the kid who works in that store. When he sees the top guys doing them, he can say to himself, “If it’s not too small for them, it’s not too small for me.” The minute you take away all the artificial barriers between you and your people, you’re on your way to phenomenal success. But it takes a bit of humility. To this day, if I walk into a Home Depot and see a customer who looks lost and confused, I walk up to him and say, “I have something to do with this company; can I help you?” if he has a question that’s beyond me, I’ll go grab a kid and say, “can you help this customer?”

- We’ve never paid anyone minimum wage at Home Depot. We had a simple belief: minimum wage, minimum talent. We always wanted to have good kids who wanted careers and not feel they had to compromise their pay. We paid them two or three bucks an hour more than minimum. We reviewed them every six months. And from the beginning we were growing like a weed, so we created enormous upside mobility.

- If there’s anything I would take a bow for throughout this whole process, it would be this: never giving up, and thinking creatively, instead of just reactively, when the chips were down. It’s a style I recommend highly. You get to enjoy lemonade instead of the lemons God gives you, and chicken salad instead of the much less tasty alternative

- As I began my tenure at Home Depot, my first role was just to lift morale. It was a big lift. I decided to do some of the same things we did at Home Depot: hold town meetings, walk the halls, talk to the staff. Put my arm around people’s shoulders, tell them how much we appreciated them and what we were going to do for them – and deliver. In other words, don’t promise pie in the sky unless you’ve got the recipe to make it

- No grand plans

- You noticed I originally named my little-startup Invemed because I was so fascinated by the health-care field, and how here I was, in 1976, up to my ass in the home-improvement business. And happy to be there. Contradictory? Sure! Life is full of left turns, and I’ve taken quite a few of them, following my nose, which has very often pointed me in the right direction. The truth is I can’t help myself: I am a deal junkie. If the phone rings, I’m like the proverbial fire-house dog – off to the races. Who knows who might be calling? More often than not, it’s someone who has a very interesting business proposition. Doesn’t matter what kind of business it is.

- Life Lessons

- It wasn’t just wealth itself that put me in that position; a lot of it was sheer stubborn curiosity. Whenever I served on a corporate board, I was notorious for asking more questions than any other director on that board. I didn’t give a shit if my question showed how stupid I was. A lot of people are scared to ask questions because they don’t want people to know how dumb they are. I’ve never had that problem. A lot of people are also afraid of falling down and hurting themselves along the way. Capitalism works, but you’ve got to make the effort, and you’ve got to be able to take the lumps. You have to have the kind of stamina that, when you get knocked down, allows you to pick yourself up and brush yourself off and move on just as if you’d never been knocked down. When I almost went broke in 1970, when I fell almost overnight from the highest mountain to the lowest valley, when I’d go home every day at 4:00pm and weed the garden and cry, I managed to go on afterward

- Don’t be in awe of anyone – public and private personas differ greatly

- Nothing more important than the name I leave my kids

- The big picture depends on a lot of smaller pictures.

- Never count the money while the game is still going

- Too many people measure success the wrong way. Money should be at the bottom of the list, not the top. I woke up soon enough to realize that if the only way you can define my life is by the size of my bank account, then I’ve failed. Fifteen or twenty years ago, a guy asked me how much I was worth and I answered without thinking, “my net worth is what good I do with what I have.”

- What distinguishes the winners from the losers is the ability to turn adversity around: resilience and creativity.

- The beautiful thing is that as much as we give, it keeps coming back: we’ve made back all the money we’ve given away, and more. What Elaine and I can’t make more of for ourselves is time. We spend it, but we can’t get it back

What I got out of it

- A really fun read with some great stories and lessons. Main ones: in any deal, always leave more on the table; think longer-term and build relationships; add more value than you take away; do the hard work and prepare; be candid, truthful, honest, yourself

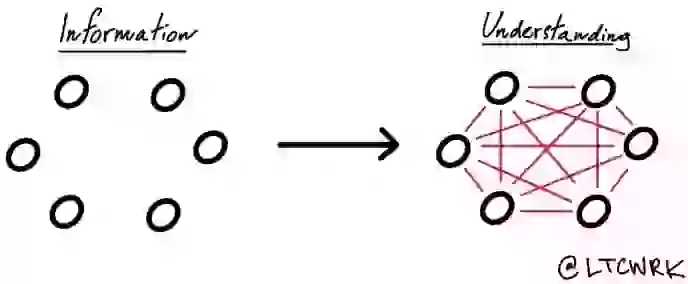

In the Latticework, we've distilled, curated, and interconnected the 750+book summaries from The Rabbit Hole. If you're looking to make the ideas from these books actionable in your day-to-day life and join a global tribe of lifelong learners, you'll love The Latticework. Join us today.