- Even “amazing” classes are useless if the learner doesn’t do something different afterward. For me, the goal of good learning design is for learners to emerge from the learning experience with new or improved capabilities that they can take back to the real world and that help them do the things they need or want to do.

- Learning Path

- If learning is a journey, what’s the gap between where they are and where they need to be? Sometimes that gap is knowledge, but just as often the gap can be skills, motivation, habit, or environment.

- Having a skill is different from having knowledge. To determine if something is a skill gap rather than a knowledge gap, you need to ask just one question: Is it reasonable to think that someone can be proficient without practice? If the answer is no, then you know you are dealing with a skill, and your learners will need practice to develop proficiency.

- To teach skills, that practice must be part of the learning journey you design.

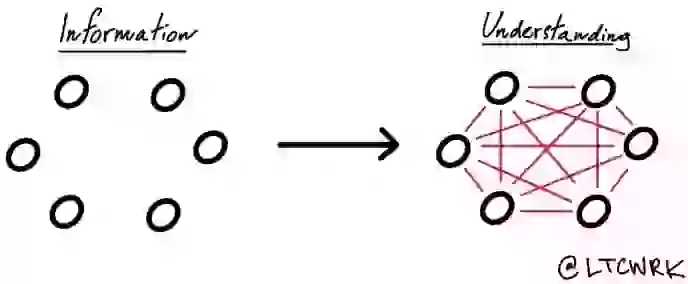

- The best learning experiences are designed with a clear destination in mind. Learn how to determine your destination with accuracy. Basically, you want your learners to have the right supplies for their journey: You also want your learners to know what to do with that information.

- Identifying and Bridging Gaps

- So when you are mapping out the route, you need to ask yourself what the journey looks like.

- Knowledge • What information does the learner need to be successful? • When along the route will they need it? • What formats would best support that?

- Skills • What will the learners need to practice to develop the needed proficiencies? • Where are their opportunities to practice?

- Motivation • What is the learner’s attitude toward the change? • Are they going to be resistant to changing course?

- Habits • Are any of the required behaviors habits? • Are there existing habits that will need to be unlearned?

- Environment • What in the environment is preventing the learner from being successful? • What is needed to support them in being successful?

- Communication • Are the goals being clearly communicated?

- So when you are mapping out the route, you need to ask yourself what the journey looks like.

- One of my all-time favorite clients was a group that did drug and alcohol prevention curriculums for middle-school kids. When they were initially explaining the curriculum to me, they talked about how a lot of earlier drug-prevention curriculums focused on information (“THIS is a crack pipe. Crack is BAD.”). Now does anyone think the main reason kids get involved with drugs is a lack of knowledge about drug paraphernalia, or because no one had ever bothered to mention that drugs are a bad idea? Instead, this group focused on practicing the heck out of handling awkward social situations involving drugs and alcohol. Kids did role-plays and skits, and brainstormed what to say in difficult situations. By ensuring that the curriculum addressed the real gaps (e.g., skills in handling challenging social situations), they were able to be much more effective. If you have a really clear sense of where the gaps are, what they are like, and how big they are, you will design much better learning solutions.

- You want to consider the question of what your learners want from a few different angles. Think about why they are there, what they want to get out of the experience, what they don’t want, and what they like (which may be different from what they want).

- Leveraging your learners as teachers. Intrinsically motivated learners are going to learn a lot on their own, and will learn even more if they share that knowledge.

- “My job as a game designer is to make the player feel smart.” I think the same is true for learning designers. Your job is to make your learners feel smart, and, even more importantly, they should feel capable.

- Don’t make every part of the learning experience required for everybody. Just don’t. Really.

- Regardless of the learning venue (classroom, elearning, informational website), it’s best to have as interactive an experience as possible. Ideally, you would construct opportunities to see how your learners are interpreting and applying what they learn, so you can correct misconceptions, extend their understanding, and identify ways to reinforce the learning.

- In determining the path for your learner, you want to do these things:

- Identify what problem you are trying to solve.

- Set a destination.

- Determine the gaps between the starting point and the destination.

- Decide how far you are going to be able to go.

- So when you are creating learning objectives, ask yourself: • Is this something the learner would actually do in the real world? • Can I tell when they’ve done it?

- The first way is to think about how sophisticated or complex you want your learner’s understanding to be. One scale for this is Bloom’s Taxonomy (this is the later version, revised by Anderson & Krathwohl in 2001): • Remember • Understand • Apply • Analyze • Evaluate • Create

- The fast parts learn, propose, and absorb shocks; the slow parts remember, integrate, and constrain. The fast parts get all the attention. The slow parts have all the power. This raises the question, What is the pace layering of learners? What can change quickly, and what changes more slowly?

- More (and better) associations will make it easier to retrieve the information. If you don’t have a good shelving system for this word, you can create a mnemonic for it. The more ways you have to find a piece of information, the easier it is to retrieve, so an item that goes on only one or two shelves is going to be harder to retrieve than an item that goes on many shelves.

- One of the most difficult types of context to create for learning situations is emotional context. So how can you create learning activities that are a better match for the real-world application? • Ensure that the practice involves recall or application.

- Ensure that the practice and assessment are high-context.

- Use job aids to change something from a recall to a recognition task. Job aids change the task from “recall the steps” to “follow these steps,” reducing the need to rely on memory. If you do use job aids, give your learners a chance to practice with the job aid as part of the learning. If you want to eventually retrieve information from your memory, you need to practice retrieving it when you study (Karpicke 2011). Retrieval practice has been well studied and is one of the most effective study methods, found in one study to be more effective than traditional studying or mind-mapping. When you are teaching, you need to make sure that your learning activities allow your learners to practice in the same way that they will need to perform.

- If learning is a journey, what’s the gap between where they are and where they need to be? Sometimes that gap is knowledge, but just as often the gap can be skills, motivation, habit, or environment.

- Memory & Feedback

- Memory relies on encoding and retrieval, so learning designers need to think about how the material gets into long-term memory, and also about what the learner can do to retrieve it later.

- People hold items in working memory only as long as they need them for some purpose. Once that purpose is satisfied, they frequently forget the items. Asking your learners to do something with the information causes them to retain it longer and increases the likelihood that that information will be encoded into long-term memory.

- So how do you attract and engage the elephant? • Tell it stories. • Surprise it. • Show it shiny things. • Tell it all the other elephants are doing it. • Leverage the elephant’s habits.

- Another way to leverage storytelling in learning design is to make people the heroes of their own story. A friend of mine who is a game designer says the purpose of game design is to make the player feel smart. Sebastian Deterding, a game researcher and academic, describes it this way: Games satisfy one of our three innate psychological needs—namely, the need to experience competence, our ability to control and affect our environment, and to get better at it.

- Somewhat counterintuitively, a longer period in between practice sessions can lead to longer overall retention. A good rule of thumb is to time the practices to how often you’ll need to use the behavior.

- The good news is that if you use the Context, Challenge, Activity, and Feedback model, or if you design a curriculum around structured goals, you have lots of built-in feedback points. You should look for opportunities to increase the frequency of feedback whenever possible.

- Increasing the frequency of feedback is great, but if you do that, you also want to have various ways to provide feedback.

- Figuring out when the check-ins need to occur can be enormously helpful. Part of designing your learning experience should be setting a schedule. • When are you going to follow up? • What will be evaluated? • What criteria will be used?

- If the structure and setup of your learning situation don’t allow for coaching follow-up, there are other ways to reach out and follow up with learners: • Create a forum online and encourage learners to report back on their experiences. • Send periodic emails with examples, tips, and opportunities for learners to self-evaluate. • Have virtual critique sessions that allow learners to post work and get feedback from the community.

- Change is a Process, Not an Event Any time you want learners to change their behavior, it’s a process and it needs to be reinforced.

- Progress & Recognition

- I think we have a similar responsibility when we design learning experiences, but I think our responsibility is to make the learner feel capable. So how can your learners feel more capable? • Show them the before and after. Your learner should be able to see how they will be different if they master the skills. What will they be able to do that they can’t do now? Will they be more capable? Will they be able to handle problems that they can’t right now? Will they have new tools to put in their professional toolbox? Show the learners what they can do and how they can get there.

- Give them real achievements. Let them do meaningful things with the material while they are learning about it.

- When researchers test people using expected and unexpected rewards, there is greater activation of anticipation and reward structures in the brain when the reward is unexpected (Berns 2001). Basically, people have a much stronger response to unexpected rewards than they do to ones they know are coming.

- Video games also do this well—we will be going along, collecting gold coins, when suddenly, after the 35th gold coin, we get the SUPER PLATINUM HAMMER OF DEATH. When something like that happens, we immediately start looking for the pattern. What was I doing that caused that to happen? What can I do to make it happen again?

- There are some specific ways to leverage social interaction to engage the elephant, including collaboration, competition, and social proof.

- Another way to have your learner be more aware of their own learning is to give learners an inventory of the content, and have them rate their level of comfort with each topic. As they go, they can adjust their ratings, either as they get more comfortable or as they realize they don’t know as much as they thought they did. While these ratings don’t mean the learners have actual proficiency, it does involve them in tracking their own understanding and focuses them on eliminating gaps.

- Passive experiences like lectures or page-turner elearning courses, where the information is just channeled to the learner, can also flow smoothly right by the learner. If the learner is actively engaging with or interested in the material, then a passive information-delivery system can still be an effective tool. But if your learner is even mildly disengaged, this same method probably won’t accomplish much. Creating opportunities to interact with the material can make a lesson even more engaging for your motivated learners.

- Cathy Moore, an outstanding elearning designer (www.cathy-moore.com), has a checklist of items that she uses to evaluate whether a learning experience is action-oriented or more of an info dump.

- Discussion topics can facilitate this (“discuss the consequences of sexual harassment complaints in the broader organization”), but you generally get better results if you give groups a more concrete purpose. They could: • Create something • Work together to teach something to the rest of the class • Argue different sides of a debate • Investigate and report back (e.g., find three good examples, or a bad example, and bring them back to the class)

- I keep TAM in mind when I design anything that requires adopting a new technology, system, or practice (which is almost everything I do). Some of the questions I ask are: • Is the new behavior genuinely useful? • If it is useful, how will the learner know that? • Is the new behavior easy to use? • If it’s not easy to use, is there anything that can be done to help that?

- So think about it—given your subject matter, who are the really influential people in your organization or in the eyes of your target audience? How can you make those opinions visible?

- Habits

- A habit is defined as “an acquired behavior pattern regularly followed until it has become almost involuntary.” (behavior = motivation + ability + trigger). So if you are trying to quit smoking, you need more than the goal (“I’m going to stop smoking”)—you need the implementation intention of how to actually do it. So you could say: If I get a craving, I will distract myself.

- If a habit seems overwhelming, make it smaller. Both Chip and Dan Heath (in their excellent book Switch) and BJ Fogg, in his Tiny Habits program, discuss the importance of identifying the smallest productive behavior and focusing on that.

- How can we make behaviors more visible and reinforce practice?

- Have learners create implementation intentions. Give learners an opportunity, or even a template, that allows them to create their own implementation intentions (“If x happens, I will do y”).

- Carve out time for specific habits. If you are trying to develop habits, it can be useful to spread them out over time and then reinforce that.

- Help tie the habit to an existing behavior. Help learners identify an existing behavior they can chain the new habit to.

- Environment & Community

- Novices need onboarding. They need to be welcomed, given some goals to achieve, and introduced to the way the community functions. • Regular participants need fresh content, activities, and people to interact with. • Masters need exclusive activities and access to content and abilities that regular participants don’t have.

- Improving the environment is about clearing out as much of the stuff that learners don’t really need to carry around in their heads, and instead letting them focus on the things that only they are able to do.

- One of the things you need to consider when putting knowledge into the world is the proximity of the knowledge to the task. By this I mean, how far from the task does the learner have to go to get the knowledge?

- Here are a few other types of job aids: • Decision trees If a process has very specific and predetermined decision points, then giving people a logical, step-by-step way to navigate those decisions can significantly improve learner performance.

- This program has also started crowdsourcing by capturing and displaying other users’ questions and answers. Leveraging your learners’ knowledge through wikis or forums can be an invaluable source of information.

- What’s everything else we could do (besides training) that will allow learners to succeed?

- To do evaluation well, you should start by defining what you are trying to evaluate. Some of the things you might want to know include: • Does my learning design function well? • Are the learners actually learning the right things? • Can the learners actually do the right things? • Are the learners actually doing the right things when they go back to the real world? The best way you answer these questions = Watch actual learners use your design.

- We can’t make anybody learn, but we can make much better learning environments for them and help each learner be the hero of their own learning journey.

What I got out of it

- Some great principle and ideas in terms of how to structure learning to really engage the people who are trying to teach - getting human nature and the environment to work for you rather than against you