- There is no panacea for peace that can be written out in a formula like a doctor's prescription. But one can set down a series of practical points—elementary principles drawn from the sum of human experience in all times. Study war and learn from its history. Keep strong, if possible. In any case, keep cool. Have unlimited patience. Never corner an opponent and always assist him to save his face. Put yourself in his shoes—so as to see things through his eyes. Avoid self-righteousness like the devil—nothing is so self-blinding. Cure yourself of two commonly fatal delusions—the idea of victory and the idea that war cannot be limited

- I would emphasize a basic value of history to the individual. As Burckhardt said, our deeper hope from experience is that it should “make us, not shrewder (for next time), but wiser (for ever).” History teaches us personal philosophy.

- Over two thousand years ago, Polybius, the soundest of ancient historians, began his History with the remark that “the most instructive, indeed the only method of learning to bear with dignity the vicissitude of fortune, is to recall the catastrophes of others.” History is the best help, being a record of how things usually go wrong. A long historical view not only helps us to keep calm in a “time of trouble” but reminds us that there is an end to the longest tunnel. Even if we can see no good hope ahead, an historical interest as to what will happen is a help in carrying on. For a thinking man, it can be the strongest check on a suicidal feeling.

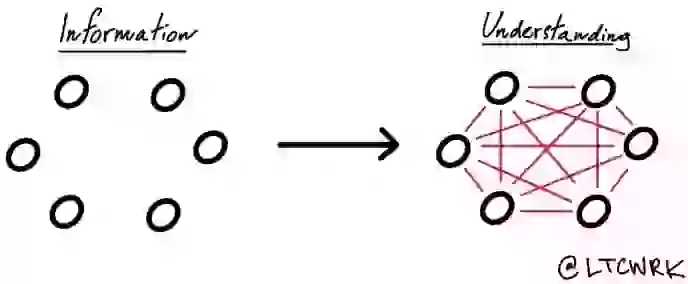

- What is the object of history? I would answer, quite simply – “truth." The object might be more cautiously expressed thus: to find out what happened while trying to find out why it happened. In other words, to seek the causal relations between events. History has limitations as guiding signpost, however, for although it can show us the right direction, it does not give detailed information about the road conditions

- NOTE: map is not the terrain

- History can show us what to avoid, even if it does not teach us what to do—by showing the most common mistakes that mankind is apt to make and to repeat. A second object lies in the practical value of history. “Fools,” said Bismarck, “say they learn by experience. I prefer to profit by other people's experience.” The study of history offers that opportunity in the widest possible measure. It is universal experience – infinitely longer, wider, and more varied than any individual’s experience.

- The point was well expressed by Polybius. “There are two roads to the reformation for mankind—one through misfortunes of their own, the other through the misfortunes of others; the former is the most unmistakable, the latter the less painful…the knowledge gained from the study of true history is the best of all educations for practical life

- Why were they not deduced? Partly because the General Staffs' study was too narrow, partly because they were blinded by their own professional interests and sentiments. But the “surprising” developments were correctly deduced from those earlier wars by certain non-official students of war who were able to think with detachment

- History is the record of man's steps and slips. It shows us that the steps have been slow and slight; the slips, quick and abounding. It provides us with the opportunity to profit by the stumbles and tumbles of our forerunners. Awareness of our limitations should make us chary of condemning those who made mistakes, but we condemn ourselves if we fail to recognize mistakes

- Viewed aright, it is the broadest of studies, embracing every aspect of life. It lays the foundation of education by showing how mankind repeats its errors and what those errors are

- In reality, reason has had a greater influence than fortune on the issue of wars that have most influenced history. Creative thought has often counted for more than courage; for more, even, than gifted leadership. It is a romantic habit to ascribe to a flash of inspiration in battle what more truly has been due to seeds long sown—to the previous development of some new military practice by the victors, or to avoidable decay in the military practice of the losers.

- Direct experience is inherently too limited to form an adequate foundation either for theory or for application. At the best it produces an atmosphere that is of value in drying and hardening the structure of thought. The greater value of indirect experience lies in its greater variety and extent. “History is universal experience”—the experience not of another but of many others under manifold conditions.

- The increasing specialization of history has tended to decrease the intelligibility of history and thus forfeit the benefit to the community

- Observing the working of committees of many kinds, I have long come to realize the crucial importance of lunchtime. Two hours or more may have been spent in deliberate discussion and careful weighing of a problem, but the last quarter of an hour often counts for more than all the rest. At 12:45pm there may be no prospect of an agreed solution, yet around about 1pm important decisions may be reached with little argument—because the attention of the members has turned to watching the hands of their watches. Those moving hands can have a remarkable effect in accelerating the movements of minds—to the point of a snap decision. The more influential members of any committee are the most likely to have important lunch engagements, and the more important the committee the more likely is this contingency. A shrewd committeeman often develops a technique based on this time calculation. He will defer his own intervention in the discussion until lunchtime is near, when the majority of the others are more inclined to accept any proposal that sounds good enough to enable them to keep their lunch engagement.

- Another danger, among “hermit” historians, is that they often attach too much value to documents. Men in high office are apt to have a keen sense of their own reputation in history. Many documents are written to deceive or conceal. Moreover, the struggles that go on behind the scenes, and largely determine the issue, are rarely recorded in documents.

- Lloyd George frequently emphasized to me in conversation that one feature that distinguished a first-rate political leader from a second-rate politician is that the former was always careful to avoid making any definite statement that could be subsequently refuted, as he was likely to be caught out in the long run.

- “Hard writing makes easy reading.” Such hard writing makes for hard thinking.

- Discernment may be primarily a gift—and a sense of proportion, too. But their development can be assisted by freedom from prejudice, which largely rests with the individual to achieve—and within his power to achieve it. Or at least to approach it. The way of approach is simple, if not easy—requiring, above all, constant self-criticism and care for precise statement.

- To view any question subjectively is self-blinding.

- Doubt is unnerving save to philosophic minds, and armies are not composed of philosophers, either at the top or at the bottom. In no activity is optimism so necessary to success, for it deals so largely with the unknown—even unto death. The margin that separates optimism from blind folly is narrow. Thus there is no cause for surprise that soldiers have so often overstepped it and become the victims of their faith.

- The point had been still more clearly expressed in the eleventh-century teaching of Chang-Tsai: “If you can doubt at points where other people feel no impulse to doubt, then you are making progress.”

- We learn too that nothing has aided the persistence of falsehood, and the evils resulting from it, more than the unwillingness of good people to admit the truth when it was disturbing to their comfortable assurance. Always the tendency continues to be shocked by natural comment and to hold certain things too “sacred” to think about.

- How rarely does one meet anyone whose first reaction to anything is to ask “Is it true?” Yet unless that is a man's natural reaction it shows that truth is not uppermost in his mind, and, unless it is, true progress is unlikely.

- Yet the longer I watch current events, the more I have come to see how many of our troubles arise from the habit, on all sides, of suppressing or distorting what we know quite well is the truth, out of devotion to a cause, an ambition, or an institution—at bottom, this devotion being inspired by our own interest.

- It was saddening to discover how many apparently honorable men would stoop to almost to anything to help their own advancement.

- A different habit, with worse effect, was the way that ambitious officers when they came in sight of promotion to the generals' list, would decide that they would bottle up their thoughts and ideas, as a safety precaution, until they reached the top and could put these ideas into practice. Unfortunately the usual result, after years of such self-repression for the sake of their ambition, was that when the bottle was eventually uncorked the contents had evaporated.

- In my experience the troubles of the world largely come from excessive regard to other interests.

- We learn from history that those who are disloyal to their own superiors are most prone to preach loyalty to their subordinates.

- Loyalty is a noble quality, so long as it is not blind and does not exclude the higher loyalty to truth and decency.

- Truth may not be absolute, but it is certain that we are likely to come nearest to it if we search for it in a purely scientific spirit and analyze the facts with a complete detachment from all loyalties save that to truth itself. It implies that one must be ready to discard one's own pet ideas and theories as the search progresses.

- Faith matters so much in times of crisis. One must have gone deep into history before reaching the conviction that truth matters more.

- All of us do foolish things—but the wiser realize what they do. The most dangerous error is failure to recognize our own tendency to error. That failure is a common affliction of authority.

- The pretense to infallibility is instinctive in a hierarchy. But to understand the cause is not to underrate the harm that the pretense has produced—in every sphere.

- Hence the duty of the good citizen who is free from the responsibility of Government is to be a watchdog upon it, lest Government impair the fundamental objects which it exists to serve. It is a necessary evil, thus requiring constant watchfulness and check.

- What is of value in “England” and “America” and worth defending is its tradition of freedom—the guarantee of its vitality. Our civilization, like the Greek, has, for all its blundering way, taught the value of freedom, of criticism of authority—and of harmonizing this with order. Anyone who urges a different system, for efficiency's sake, is betraying the vital tradition.

- We learn from history that self-made despotic rulers follow a standard pattern. In gaining power: They exploit, consciously or unconsciously, a state of popular dissatisfaction with the existing regime or of hostility between different sections of the people. On gaining power: They soon begin to rid themselves of their chief helpers, “discovering” that those who brought about the new order have suddenly become traitors to it. This political confidence trick, itself a familiar string of tricks, has been repeated all down the ages. Yet it rarely fails to take in a fresh generation.

- We learn from history that time does little to alter the psychology of dictatorship. The effect of power on the mind of the man who possesses it, especially when he has gained it by successful aggression, tends to be remarkably similar in every age and in every country.

- Bad means lead to no good end.

- But “anti-Fascism” or “anti-Communism” is not enough. Nor is even the defense of freedom. What has been gained may not be maintained, against invasion without and erosion within, if we are content to stand still. The peoples who are partially free as a result of what their forebears achieved in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries must continue to spread the gospel of freedom and work for the extension of the conditions, social and economic as well as political, which are essential to make men free.

- We learn from history that the compulsory principle always breaks down in practice. It is practicable to prevent men doing something; moreover that principle of restraint, or regulation, is essentially justifiable in so far as its application is needed to check interference with others' freedom. But it is not, in reality, possible to make men do something without risking more than is gained from the compelled effort. The method may appear practicable, because it often works when applied to those who are merely hesitant. When applied to those who are definitely unwilling it fails, however, because it generates friction and fosters subtle forms of evasion that spoil the effect which is sought. The test of whether a principle works is to be found in the product. Efficiency springs from enthusiasm—because this alone can develop a dynamic impulse. Enthusiasm is incompatible with compulsion—because it is essentially spontaneous. Compulsion is thus bound to deaden enthusiasm—because it dries up the source. The more an individual, or a nation, has been accustomed to freedom, the more deadening will be the effect of a change to compulsion.

- Conscription does not fit the conditions of modern warfare—its specialized technical equipment, mobile operations, and fluid situations. Success increasingly depends on individual initiative, which in turn springs from a sense of personal responsibility—these senses are atrophied by compulsion. Moreover, every unwilling man is a germ carrier, spreading infection to an extent altogether disproportionate to the value of the service he is forced to contribute.

- Unless the great majority of a people are willing to give their services there is something radically at fault in the state itself. In that case the state is not likely or worthy to survive under test—and compulsion will make no serious difference.

- But the deeper I have gone into the study of war and the history of the past century the further I have come toward the conclusion that the development of conscription has damaged the growth of the idea of freedom in the Continental countries and thereby damaged their efficiency also—by undermining the sense of personal responsibility.

- NOTE: great parallels to business. Giving away ownership and responsibility gets people all-in, to self-police, to be your best salesman and advocates. Forcing them to try to act this way never works

- I believe that freedom is the foundation of efficiency, both national and military. Thus it is a practical folly as well as a spiritual surrender to “go totalitarian” as a result of fighting for existence against the totalitarian states. Cut off the incentive to freely given service and you dry up the life source of a free community.

- Reforms that last are those that come naturally, and with less friction, when men's minds have become ripe for them. A life spent in sowing a few grains of fruitful thought is a life spent more effectively than in hasty action that produces a crop of weeds. That leads us to see the difference, truly a vital difference, between influence and power.

- History shows that a main hindrance to real progress is the ever-popular myth of the “great man.” While “greatness” may perhaps be used in a comparative sense, if even then referring more to particular qualities than to the embodied sum, the “great man” is a clay idol whose pedestal has been built up by the natural human desire to look up to someone, but whose form has been carved by men who have not yet outgrown the desire to be regarded, or to picture themselves, as great men.

- We learn from history that expediency has rarely proved expedient.

- NOTE: John Wooden – be quick but don’t hurry

- Civilization is built on the practice of keeping promises. It may not sound a high attainment, but if trust in its observance be shaken the whole structure cracks and sinks. Any constructive effort and all human relations—personal, political, and commercial—depend on being able to depend on promises.

- NOTE: like any high performing culture, trust is at the center of it all. Not being able to depend on promises erodes trust

- It is immoral to make promises that one cannot in practice fulfill—in the sense that the recipient expects.

- I have come to think that accuracy, in the deepest sense, is the basic virtue—the foundation of understanding, supporting the promise of progress. The cause of most troubles can be traced to excess; the failure to check them to deficiency; their prevention lies in moderation. So in the case of troubles that develop from spoken or written communication, their cause can be traced to overstatement, their maintenance to understatement, while their prevention lies in exact statement. It applies to private as well as to public life.

- Studying their effect, one is led to see that the germs of war lie within ourselves—not in economics, politics, or religion as such. How can we hope to rid the world of war until we have cured ourselves of the originating causes?

- Any history of war which treats only of its strategic and political course is merely a picture of the surface. The personal currents run deeper and may have a deeper influence on the outcome.

- We learn from history that complete victory has never been completed by the result that the victors always anticipate—a good and lasting peace. For victory has always sown the seeds of a fresh war, because victory breeds among the vanquished a desire for vindication and vengeance and because victory raises fresh rivals.

- NOTE: dialectical materialism

- A too complete victory inevitably complicates the problem of making a just and wise peace settlement. Where there is no longer the counterbalance of an opposing force to control the appetites of the victors, there is no check on the conflict of views and interests between the parties to the alliance. The divergence is then apt to become so acute as to turn the comradeship of common danger into the hospitality of mutual dissatisfaction—so that the ally of one war becomes the enemy in the next.

- Where the two sides are too evenly matched to offer a reasonable chance of early success to either, the statesman is wise who can learn something from the psychology of strategy. It is an elementary principle of strategy that, if you find your opponent in a strong position costly to force, you should leave him a line of retreat—as the quickest way of loosening his resistance. It should, equally, be a principle of policy, especially in war, to provide your opponent with a ladder by which he can climb down.

- War is profitable only if victory is quickly gained. Only an aggressor can hope to gain a quick victory. If he is frustrated, the war is bound to be long, and mutually ruinous, unless it is brought to an end by mutual agreement.

- The history of ancient Greece showed that, in a democracy, emotion dominates reason to a greater extent than in any other political system, thus giving freer rein to the passions which sweep a state into war and prevent it getting out—at any point short of the exhaustion and destruction of one or other of the opposing sides.

- It was because Wellington really understood war that he became so good at securing peace. He was the least militaristic of soldiers and free from the lust of glory. It was because he saw the value of peace that he became so unbeatable in war. For he kept the end in view, instead of falling in love with the means. Unlike Napoleon, he was not infected by the romance of war, which generates illusions and self-deceptions. That was how Napoleon had failed and Wellington prevailed.

- One of the clear lessons that history teaches is that no agreement between Governments has had any stability beyond their recognition that it is in their own interests to continue to adhere to it. I cannot conceive that any serious student of history would be impressed by such a hollow phrase as “the sanctity of treaties.”

- We must face the fact that international relations are governed by interests and not by moral principles. Then it can be seen that the validity of treaties depends on mutual convenience. This can provide an effective guarantee.

- Any plan for peace is apt to be not only futile but dangerous. Like most planning, unless of a mainly material kind, it breaks down through disregard of human nature. Worse still, the higher the hopes that are built on such a plan, the more likely that their collapse may precipitate war.

- For whoever habitually suppresses the truth in the interests of tact will produce a deformity from the womb of his thought.

- Opposition to the truth is inevitable, especially if it takes the form of a new idea, but the degree of resistance can be diminished—by giving thought not only to the aim but to the method of approach. Avoid a frontal attack on a long-established position; instead, seek to turn it by a flank movement, so that a more penetrable side is exposed to the thrust of truth. But in any such indirect approach, take care not to diverge from the truth—for nothing is more fatal to its real advancement than to lapse into untruth.

- Even among great scholars there is no more unhistorical fallacy than that, in order to command, you must learn to obey.

- A model boy rarely goes far, and even when he does he is apt to falter when severely tested. A boy who conforms immaculately to school rules is not likely to grow into a man who will conquer by breaking the stereotyped professional rules of his time—as conquest has most often been achieved. Still less does it imply the development of the wide views necessary in a man who is not merely a troop commander but the strategic adviser of his Government. The wonderful thing about Lee's generalship is not his legendary genius but the way he rose above his handicaps—handicaps that were internal even more than external.

- the deeper the study of modern war is carried the stronger grows the conviction of its futility.

- The more that warfare is “formalized” the less damaging it proves. Past efforts in this direction have had more success than is commonly appreciated.

- The habit of violence takes much deeper root in irregular warfare than it does in regular warfare. In the latter it is counteracted by the habit of obedience to constituted authority, whereas the former makes a virtue of defying authority and violating rules. It becomes very difficult to rebuild a country, and a stable state, on such an undermined foundation.

- Vitality springs from diversity—which makes for real progress so long as there is mutual toleration, based on the recognition that worse may come from an attempt to suppress differences than from acceptance of them.

- To put it another way, it seems to me that the spiritual development of humanity as a whole is like a pyramid, or a mountain peak, where all angles of ascent tend to converge the higher they climb. On the one hand this convergent tendency, and the remarkable degree of agreement that is to be found on the higher levels, appears to me the strongest argument from experience that morality is absolute and not merely relative and that religious faith is not a delusion.

- Manners are apt to be regarded as a surface polish. That is a superficial view. They arise from an inward control. A fresh realization of their importance is needed in the world today, and their revival might prove the salvation of civilization. For only manners in the deeper sense—of mutual restraint for mutual security—can control the risk that outbursts of temper over political and social issues may lead to mutual destruction in the atomic age.

- Truth is a spiral staircase. What looks true on one level may not be true on the next higher level. A complete vision must extend vertically as well as horizontally—not only seeing the parts in relation to one another but embracing the different planes. Ascending the spiral, it can be seen that individual security increases with the growth of society, that local security increases when linked to a wider organization, that national security increases when nationalism decreases and would become much greater if each nation's claim to sovereignty were merged in a super-national body.

What I got out of it

- Not quite Durant's Lessons of History but one of the best "meta" books on history I've come across. The lessons to be gained from in-depth study of history and why it is worth it, and why we don't