- Environment and Structure

- What does make a significant difference along the whole intelligence spectrum is something else: how much self-discipline or self-control one uses to approach the tasks at hand. Luckily, this is not the whole story. We know today that self-control and self-discipline have much more to do with our environment than with ourselves (cf. Thaler, 2015, ch. 2) – and the environment can be changed. Nobody needs willpower not to eat a chocolate bar when there isn’t one around. And nobody needs willpower to do something they wanted to do anyway. Every task that is interesting, meaningful and well-defined will be done, because there is no conflict between long- and short-term interests. Having a meaningful and well-defined task beats willpower every time. Not having willpower, but not having to use willpower indicates that you set yourself up for success. This is where the organisation of writing and note-taking comes into play.

- Good structure allows you to do that, to move seamlessly from one task to another – without threatening the whole arrangement or losing sight of the bigger picture. Having a clear structure to work in is completely different from making plans about something. If you make a plan, you impose a structure on yourself; it makes you inflexible. To keep going according to plan, you have to push yourself and employ willpower. This is not only demotivating, but also unsuitable for an open-ended process like research, thinking or studying in general, where we have to adjust our next steps with every new insight, understanding or achievement – which we ideally have on a regular basis and not just as an exception. Even though planning is often at odds with the very idea of research and learning, it is the mantra of most study guides and self-help books on academic writing. How do you plan for insight, which, by definition, cannot be anticipated? It is a huge misunderstanding that the only alternative to planning is aimless messing around. The challenge is to structure one’s workflow in a way that insight and new ideas can become the driving forces that push us forward.

- The best way to deal with complexity is to keep things as simple as possible and to follow a few basic principles. The simplicity of the structure allows complexity to build up where we want it: on the content level. There is quite extensive empirical and logical research on this phenomenon (for an overview: cf. Sull and Eisenhardt, 2015). Taking smart notes is as simple as it gets.

- Luhmann was able to focus on the important things right in front of him, pick up quickly where he left off and stay in control of the process because the structure of his work allowed him to do this. If we work in an environment that is flexible enough to accommodate our work rhythm, we don’t need to struggle with resistance. Studies on highly successful people have proven again and again that success is not the result of strong willpower and the ability to overcome resistance, but rather the result of smart working environments that avoid resistance in the first place (cf. Neal et al. 2012; Painter et al. 2002; Hearn et al. 1998). Instead of struggling with adverse dynamics, highly productive people deflect resistance, very much like judo champions. This is not just about having the right mindset, it is also about having the right workflow. It is the way Luhmann and his slip-box worked together that allowed him to move freely and flexibly between different tasks and levels of thinking. It is about having the right tools and knowing how to use them – and very few understand that you need both.

- Assemble notes and bring them into order, turn these notes into a draft, review it and you are done.

- The Process

- Writing notes accompanies the main work and, done right, it helps with it. Writing is, without dispute, the best facilitator for thinking, reading, learning, understanding and generating ideas we have. Notes build up while you think, read, understand and generate ideas, because you have to have a pen in your hand if you want to think, read, understand and generate ideas properly anyway. If you want to learn something for the long run, you have to write it down. If you want to really understand something, you have to translate it into your own words. Thinking takes place as much on paper as in your own head. “Notes on paper, or on a computer screen [...] do not make contemporary physics or other kinds of intellectual endeavour easier, they make it possible,” neuroscientist Neil Levy concludes in the introduction to the Oxford Handbook of Neuroethics, summarizing decades of research. Neuroscientists, psychologists and other experts on thinking have very different ideas about how our brains work, but, as Levy writes: “no matter how internal processes are implemented, (you) need to understand the extent to which the mind is reliant upon external scaffolding.” (2011, 270)

- Make permanent notes. Now turn to your slip-box. Go through the notes you made in step one or two (ideally once a day and before you forget what you meant) and think about how they relate to what is relevant for your own research, thinking or interests. This can soon be done by looking into the slip-box – it only contains what interests you anyway. The idea is not to collect, but to develop ideas, arguments and discussions. Does the new information contradict, correct, support or add to what you already have (in the slip-box or on your mind)? Can you combine ideas to generate something new? What questions are triggered by them? Write exactly one note for each idea and write as if you were writing for someone else: Use full sentences, disclose your sources, make references and try to be as precise, clear and brief as possible. Throw away the fleeting notes from step one and put the literature notes from step two into your reference system. You can forget about them now. All that matters is going into the slip-box.

- We constantly encounter interesting ideas along the way and only a fraction of them are useful for the particular paper we started reading it for. Why let them go to waste? Make a note and add it to your slip-box. It improves it. Every idea adds to what can become a critical mass that turns a mere collection of ideas into an idea-generator. A typical work day will contain many, if not all, of these steps: You read and take notes. You build connections within the slip-box, which in itself will spark new ideas. You write them down and add them to the discussion. You write on your paper, notice a hole in the argument and have another look in the file system for the missing link. You follow up on a footnote, go back to research and might add a fitting quote to one of your papers in the making.

- The whole workflow becomes complicated: There is the technique of underlining important sentences (sometimes in different colours or shapes), commenting in the margins of a text, writing excerpts, employing reading methods with acronyms like SQ3R[8] or SQ4R,[9] writing a journal, brainstorming a topic or following multi-step question sheets – and then there are, of course, the one thousand and twelve apps and programs that are supposed to help with learning and writing. Few of these techniques are particularly complicated in themselves, but they are usually used without any regard to the actual workflow, which then quickly becomes a mess. As nothing really fits together, working within this arrangement becomes extremely complicated indeed and difficult to get anything done. And if you stumble upon one idea and think that it might connect to another idea, what do you do when you employ all these different techniques? Go through all your books to find the right underlined sentence? Reread all your journals and excerpts? And what do you do then? Write an excerpt about it? Where do you save it and how does this help to make new connections? Every little step suddenly turns into its own project without bringing the whole much further forward. Adding another promising technique to it, then, would make things only worse.

- That is why the slip-box is not introduced as another technique, but as a crucial element in an overarching workflow that is stripped of everything that could distract from what is important. Good tools do not add features and more options to what we already have, but help to reduce distractions from the main work, which here is thinking. The slip-box provides an external scaffold to think in and helps with those tasks our brains are not very good at, most of all objective storage of information. That is pretty much it. To have an undistracted brain to think with and a reliable collection of notes to think in is pretty much all we need. Everything else is just clutter.

- We need four tools:

- Something to write with and something to write on (pen and paper will do)

- A reference management system (the best programs are free)

- The slip-box (the best program is free)

- An editor (whatever works best for you: very good ones are free)

- More is unnecessary, less is impossible.

- Some suggestions: Zotero, takesmartnotes.com, Zettelkasten, zettelkasten.danielluedecke.de

- This book is based on another assumption: Studying does not prepare students for independent research. It is independent research.

- We tend to think that big transformations have to start with an equally big idea. But more often than not, it is the simplicity of an idea that makes it so powerful (and often overlooked in the beginning).

- The slip-box is the shipping container of the academic world. Instead of having different storage for different ideas, everything goes into the same slip-box and is standardised into the same format. Instead of focusing on the in-between steps and trying to make a science out of underlining systems, reading techniques or excerpt writing, everything is streamlined towards one thing only: insight that can be published. The biggest advantage compared to a top-down storage system organised by topics is that the slip-box becomes more and more valuable the more it grows, instead of getting messy and confusing. If you sort by topic, you are faced with the dilemma of either adding more and more notes to one topic, which makes them increasingly hard to find, or adding more and more topics and subtopics to it, which only shifts the mess to another level. The first system is designed to find things you deliberately search for, putting all the responsibility on your brain. The slip-box is designed to present you with ideas you have already forgotten, allowing your brain to focus on thinking instead of remembering.

- Even though the slip-box, being organised bottom-up, does not face the trade-off problem between too many or too few topics, it too can lose its value when notes are added to it indiscriminately. It can only play out its strengths when we aim for a critical mass, which depends not only on the number of notes, but also their quality and the way they are handled. To achieve a critical mass, it is crucial to distinguish clearly between three types of notes:

- Fleeting notes, which are only reminders of information, can be written in any kind of way and will end up in the trash within a day or two.

- Permanent notes, which will never be thrown away and contain the necessary information in themselves in a permanently understandable way. They are always stored in the same way in the same place, either in the reference system or, written as if for print, in the slip-box.

- Project notes, which are only relevant to one particular project. They are kept within a project-specific folder and can be discarded or archived after the project is finished. Only if the notes of these three categories are kept separated it will be possible to build a critical mass of ideas within the slip-box. One of the major reasons for not getting much writing or publishing done lies in the confusion of these categories.

- Every question that emerges out of our slip-box will naturally and handily come with material to work with. If we look into our slip-box to see where clusters have built up, we not only see possible topics, but topics we have already worked on – even if we were not able to see it up front. The idea that nobody ever starts from scratch suddenly becomes very concrete. If we take it seriously and work accordingly, we literally never have to start from scratch again.

- You may remember from school the difference between an exergonic and an endergonic reaction. In the first case, you constantly need to add energy to keep the process going. In the second case, the reaction, once triggered, continues by itself and even releases energy. The dynamics of work are not so different. Sometimes we feel like our work is draining our energy and we can only move forward if we put more and more energy into it. But sometimes it is the opposite. Once we get into the workflow, it is as if the work itself gains momentum, pulling us along and sometimes even energizing us. This is the kind of dynamic we are looking for. A good workflow can easily turn into a virtuous circle, where the positive experience motivates us to take on the next task with ease, which helps us to get better at what we are doing, which in return makes it more likely for us to enjoy the work, and so on. But if we feel constantly stuck in our work, we will become demotivated and much more likely to procrastinate, leaving us with fewer positive or even bad experiences like missed deadlines.

- Feedback loops are not only crucial for the dynamics of motivation, but also the key element to any learning process. Nothing motivates us more than the experience of becoming better at what we do. And the only chance to improve in something is getting timely and concrete feedback. Seeking feedback, not avoiding it, is the first virtue of anyone who wants to learn, or in the more general terms of psychologist Carol Dweck, to grow.

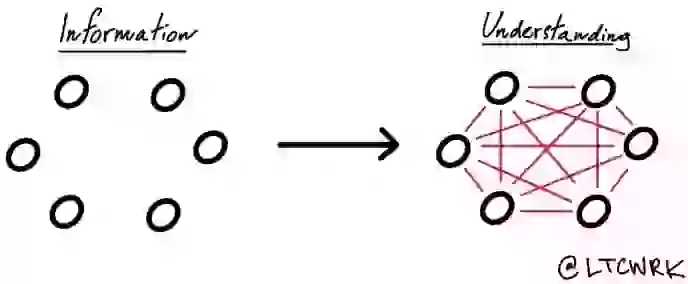

- Our brains work not that differently in terms of interconnectedness. Psychologists used to think of the brain as a limited storage space that slowly fills up and makes it more difficult to learn late in life. But we know today that the more connected information we already have, the easier it is to learn, because new information can dock to that information. Yes, our ability to learn isolated facts is indeed limited and probably decreases with age. But if facts are not kept isolated nor learned in an isolated fashion, but hang together in a network of ideas, or “latticework of mental models” (Munger, 1994), it becomes easier to make sense of new information.

- Oshin Vartanian compared and analysed the daily workflows of Nobel Prize winners and other eminent scientists and concluded that it is not a relentless focus, but flexible focus that distinguishes them. “Specifically, the problem-solving behavior of eminent scientists can alternate between extraordinary levels of focus on specific concepts and playful exploration of ideas.

- The moment we stop making plans is the moment we start to learn. It is a matter of practice to become good at generating insight and write good texts by choosing and moving flexibly between the most important and promising tasks, judged by nothing else than the circumstances of the given situation.

- Things we understand are connected, either through rules, theories, narratives, pure logic, mental models or explanations. And deliberately building these kinds of meaningful connections is what the slip-box is all about.

- Every step is accompanied by questions like: How does this fact fit into my idea of …? How can this phenomenon be explained by that theory? Are these two ideas contradictory or do they complement each other? Isn’t this argument similar to that one? Haven’t I heard this before? And above all: What does x mean for y? These questions not only increase our understanding, but facilitate learning as well. Once we make a meaningful connection to an idea or fact, it is difficult not to remember it when we think about what it is connected with.

- It is safe to argue that a reliable and standardised working environment is less taxing on our attention, concentration and willpower, or, if you like, ego.

- Breaks are much more than just opportunities to recover. They are crucial for learning. They allow the brain to process information, move it into long-term memory and prepare it for new information. If we don’t give ourselves a break in between work sessions, be it out of eagerness or fear of forgetting what we were doing, it can have a detrimental effect on our efforts. To have a walk even a nap supports learning and thinking.

- If you understand what you read and translate it into the different context of your own thinking, materialised in the slip-box, you cannot help but transform the findings and thoughts of others into something that is new and your own. It works both ways: The series of notes in the slip-box develops into arguments, which are shaped by the theories, ideas and mental models you have in your head. And the theories, ideas and mental models in your head are also shaped by the things you read.

- “I always have a slip of paper at hand, on which I note down the ideas of certain pages. On the backside I write down the bibliographic details. After finishing the book I go through my notes and think how these notes might be relevant for already written notes in the slip-box. It means that I always read with an eye towards possible connections in the slip-box.”

- Without a clear purpose for the notes, taking them will feel more like a chore than an important step within a bigger project.

- Here, everything is about building up a critical mass of useful notes in the slip-box, which gives us a clear idea of how to read and how to take literature notes.

- While selectivity is the key to smart note-taking, it is equally important to be selective in a smart way. Unfortunately, our brains are not very smart in selecting information by default. While we should seek out dis-confirming arguments and facts that challenge our way of thinking, we are naturally drawn to everything that makes us feel good, which is everything that confirms what we already believe we know. The very moment we decide on a hypothesis, our brains automatically go into search mode, scanning our surroundings for supporting data, which is neither a good way to learn nor research. Worse, we are usually not even aware of this confirmation bias (or myside bias). The classic role model would be Charles Darwin. He forced himself to write down (and therefore elaborate on) the arguments that were the most critical of his theories. “I had [...] during many years followed a golden rule, namely, that whenever a published fact, a new observation or thought came across me, which was opposed to my general results, to make a memorandum of it without fail and at once; for I had found by experience that such facts and thoughts were far more apt to escape from the memory than favorable ones. Owing to this habit, very few objections were raised against my views, which I had not at least noticed and attempted to answer.”

- Writing brief accounts on the main ideas of a text instead of collecting quotes.

- Putting notes into the slip-box, however, is like investing and reaping the rewards of compounded interest (which would in this example almost pay for the whole flat). And likewise, the sum of the slip-box content is worth much more than the sum of the notes. More notes mean more possible connections, more ideas, more synergy between different projects and therefore a much higher degree of productivity.

- Add a note to the slip-box either behind the note you directly refer to or, if you do not follow up on a specific note, just behind the last note in the slip-box. Number it consecutively. The Zettelkasten numbers the notes automatically. “New note” will just add a note with a new number. If you click “New note sequence,” the new note will be registered at the same time as the note that follows the note currently active on the screen. But you can always add notes “behind” other notes anytime later. Each note can follow multiple other notes and therefore be part of different note sequences. 2. Add links to other notes or links on other notes to your new note. 3. Make sure it can be found from the index; add an entry in the index if necessary or refer to it from a note that is connected to the index. 4. Build a Latticework of Mental Models

- Because the slip-box is not intended to be an encyclopaedia, but a tool to think with, we don’t need to worry about completeness.

- Keywords should always be assigned with an eye towards the topics you are working on or interested in, never by looking at the note in isolation.

- The beauty of this approach is that we co-evolve with our slip-boxes: we build the same connections in our heads while we deliberately develop them in our slip-box – and make it easier to remember the facts as they now have a latticework we can attach them to. If we practice learning not as a pure accumulation of knowledge, but as an attempt to build up a latticework of theories and mental models to which information can stick, we enter a virtuous circle where learning facilitates learning.

- Learning, Thinking, & Retrieval

- Without these tools and reference points, no professional reading or understanding would be possible. We would read every text in the same way: like a novel. But with the learned ability of spotting patterns, we can enter the circle of virtuosity: Reading becomes easier, we grasp the gist quicker, can read more in less time, and can more easily spot patterns and improve our understanding of them.

- The ability to spot patterns, to question the frames used and detect the distinctions made by others, is the precondition to thinking critically and looking behind the assertions of a text or a talk. Being able to re-frame questions, assertions and information is even more important than having an extensive knowledge, because without this ability, we wouldn’t be able to put our knowledge to use.

- Developing arguments and ideas bottom-up instead of top-down is the first and most important step to opening ourselves up for insight. We should be able to focus on the most insightful ideas we encounter and welcome the most surprising turns of events without jeopardizing our progress or, even better, because it brings our project forward.

- It becomes easier to seek out dis-confirming data with practice and can become quite addictive. The experience of how one piece of information can change the whole perspective on a certain problem is exciting.

- ‘Have the courage to use your own understanding,’ is therefore the motto of the Enlightenment.” (Kant 1784)

- Only the actual attempt to retrieve information will clearly show us if we have learned something or not.

- When we try to answer a question before we know how to, we will later remember the answer better, even if our attempt failed (Arnold and McDermott 2013). If we put effort into the attempt of retrieving information, we are much more likely to remember it in the long run, even if we fail to retrieve it without help in the end (Roediger and Karpicke 2006). Even without any feedback, we will be better off if we try to remember something ourselves (Jang et al. 2012). The empirical data is pretty unambiguous, but these learning strategies do not necessarily feel right.

- It is not surprising, therefore, that the best-researched and most successful learning method is elaboration. It is very similar to what we do when we take smart notes and combine them with others, which is the opposite of mere re-viewing (Stein et al. 1984) Elaboration means nothing other than really thinking about the meaning of what we read, how it could inform different questions and topics and how it could be combined with other knowledge.

- One difference stood out as critical: The ability to think beyond the given frames of a text (Lonka 2003, 155f). Experienced academic readers usually read a text with questions in mind and try to relate it to other possible approaches, while inexperienced readers tend to adopt the question of a text and the frames of the argument and take it as a given. What good readers can do is spot the limitations of a particular approach and see what is not mentioned in the text.

- Richard Feynman once had a visitor in his office, a historian who wanted to interview him. When he spotted Feynman’s notebooks, he said how delighted he was to see such “wonderful records of Feynman’s thinking.” “No, no!” Feynman protested. “They aren’t a record of my thinking process. They are my thinking process. I actually did the work on the paper.” “Well,” the historian said, “the work was done in your head, but the record of it is still here.” “No, it’s not a record, not really. It’s working. You have to work on paper, and this is the paper.”

- If we instead focus on “retrieval strength,” we instantly start to think strategically about what kind of cues should trigger the retrieval of a memory.

- What does help for true, useful learning is to connect a piece of information to as many meaningful contexts as possible, which is what we do when we connect our notes in the slip-box with other notes. Making these connections deliberately means building up a self-supporting network of interconnected ideas and facts that work reciprocally as cues for each other. Learned right, which means understanding, which means connecting in a meaningful way to previous knowledge, information almost cannot be forgotten anymore and will be reliably retrieved if triggered by the right cues. Moreover, this new learned knowledge can provide more possible connections for new information. If you focus your time and energy on understanding, you cannot help but learn.

- Being experienced with a problem and intimately familiar with the tools and devices we work with, ideally to the point of virtuosity, is the precondition for discovering their inherent possibilities, writes Ludwik Fleck, a historian of science

- Steven Johnson, who wrote an insightful book about how people in science and in general come up with genuine new ideas, calls it the “slow hunch.” As a precondition to make use of this intuition, he emphasises the importance of experimental spaces where ideas can freely mingle

- Studies on creativity with engineers show that the ability to find not only creative, but functional and working solutions for technical problems is equal to the ability to make abstractions. The better an engineer is at abstracting from a specific problem, the better and more pragmatic his solutions will be – even for the very problem he abstracted from (Gassmann and Zeschky, 2008, 103). Abstraction is also the key to analyse and compare concepts, to make analogies and to combine ideas; this is especially true when it comes to interdisciplinary work (Goldstone and Wilensky 2008).

- One of the most famous figures to illustrate this skill is the mathematician Abraham Wald (Mangel and Samaniego 1984). During World War II, he was asked to help the Royal Air Force find the areas on their planes that were most often hit by bullets so they could cover them with more armour. But instead of counting the bullet holes on the returned planes, he recommended armouring the spots where none of the planes had taken any hits. The RAF forgot to take into account what was not there to see: All the planes that didn’t make it back. The RAF fell for a common error in thinking called survivorship bias (Taleb 2005). The other planes didn’t make it back because they were hit where they should have had extra protection, like the fuel tank. The returning planes could only show what was less relevant.

- IAnother key point: Try working on different manuscripts at the same time. While the slip-box is already helpful to get one project done, its real strength comes into play when we start working on multiple projects at the same time. The slip-box is in some way what the chemical industry calls “verbund.” This is a setup in which the inevitable by-product of one production line becomes the resource for another, which again produces by-products that can be used in other processes and so on, until a network of production lines becomes so efficiently intertwined that there is no chance of an isolated factory competing with it anymore. This is advantageous not only because we make progress on the next papers or books while we are still working on the current one, but also because it allows us to switch to other projects whenever we get stuck or bored. Remember: Luhmann’s answer to the question of how one person could be so productive was that he never forced himself to do anything and only did what came easily to him. “When I am stuck for one moment, I leave it and do something else.” When he was asked what else he did when he was stuck, his answer was: “Well, writing other books. I always work on different manuscripts at the same time.

- There is one exception, though: we most certainly act according to our intention if we happen to intend to do exactly what we used to do before. It is really easy to predict the behaviour of people in the long run. In all likelihood, we will do in a month, a year or two years from now exactly what we have done before: eat as many chocolates as before, go to the gym as often as before, and get ourselves into the same kinds of arguments with our partners as before. To put it differently, good intentions don’t last very long, usually. We have the best chance to change our behaviour over the long term if we start with a realistic idea about the difficulties of behavioural change

- Change is possible when the solution appears to be simple.

What I got out of it

- Feel like somebody was explaining my system to me! This is a bit more rigorous, but much of how I take notes, recall info, fit them into my latticework, helps with ideation, recall, and creativity - exactly like this structure outlines!