- We began construction of a conceptual system in Chapter 2 by assuming the meanings of a few logical, temporal, and spatial concepts, and we used them to define concepts of mechanics and physics. Thus, starting with concepts taken from the formal sciences, we developed a few central concepts of the physical sciences and, using them, then proceeded to the behavioral sciences. The order of this development reflects the commonly held belief that the concepts of science, and hence the sciences themselves, are hierarchical in nature. The concepts of the formal and physical sciences are believed to be fundamental in some sense, and the concepts of the behavioral sciences are believed to be derived from them…We believe that all the concepts of science are interdependent, and therefore illumination of the meaning of any member of the system of scientific concepts can illuminate to varying degrees, each of the other concepts in the system. As we have noted earlier, historical ordering is often confused with logical or epistemological ordering. We do not take the concepts we begin with to be basic in any way, but rather we maintain that they are definable in terms of the concepts derived from them. To show that this is the case is not to close a vicious cycle, but to complete a cycle in which the initial concepts are enriched. It opens the way for another such cycle in which the meanings of all the concepts can be further enhanced.

- Logic - the art of thinking and reasoning in strict accordance with the limitation and incapacities of the human misunderstanding. - The Devil's Dictionary

- While acknowledging that disciplinary segmentation evolved as a way of coping with the complexity of the universe and the study of it, systems theorists challenge the presumption that the world is best understood by segmenting our investigation of it into discrete disciplinary areas, each of which specializes in a particular perspective, level of analysis, or phenomena. Systems theorists argue that such an approach may not be the most appropriate one for meaningfully addressing the complexity of life, and also point to the limitations this structure imposes on the advancement of general and integrative knowledge. Perhaps, one of the most tangible manifestations of this problem can be seen in the curriculum of the average undergraduate student, which offers up a biological view of life in the first hour, a psychological view second hour, a communication view third hour, sociological fourth, political science fifth, and so on, as if human behavior could be best comprehended when compartmentalized in such a manner.

- Philosophy's principal function in the nineteenth century was to synthesize the findings of the various scientific disciplines into one cohesive body of knowledge about natural phenomena. The biggest barrier to such synthesis is the difference between living and nonliving systems, not just the diversity of disciplines

- Nature does not come to us in disciplinary form. Phenomena are not physical, chemical, biological, and so on. The disciplines are the ways we study phenomena; they emerge from points of view, not from what is viewed. Hence the disciplinary nature of science is a filing system of knowledge. Its organization is not to be confused with the organization of nature itself...In brief, the need to assemble knowledge of our world into one cohesive view derives from the necessity to take it apart in order to penetrate it in depth.

- System: a set of interrelated elements, each of which is related directly or indirectly to every other element, and no subset of which is unrelated to any other subset. Hence, a system is composed of at least 2 elements and a relation that holds each of its elements and at least one other element in the set. The elements form a completely connected set that is not decomposable into unrelated subsets. Therefore, although a system may itself be part of a larger system it cannot be decomposed into independent subsystems

- Abstract system - a system all of whose elements are concepts

- Concrete system - a system at least two of whose elements are objects

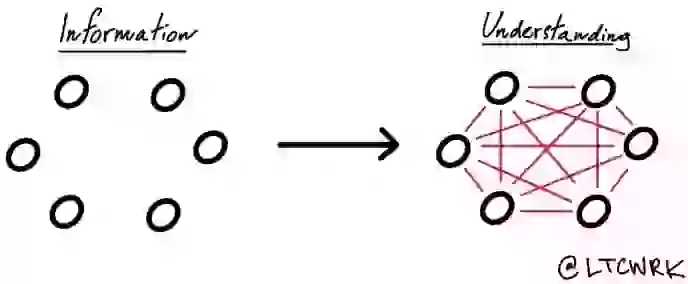

- Another major aspect of the individuality of a system is its response capabilities or aptitudes. In considering psychological systems we use the terms in this connection - knowledge, understanding, and intelligence. The first two terms have received more attention from philosophers than from psychologists, but intelligence has been a major preoccupation of psychologists. The meaning of these concepts and the difference among them is far from clear in either ordinary or technical usage. Knowledge - awareness or possession of a fact or state of affairs and/or the possession of a practical skill. Understanding implies something deeper than knowledge - apprehending the meaning or significance of what is known, responsiveness to whatever affects efficiency. Intelligence has to do with the rate at which a subject can learn (learning is the increase in degree of knowledge or understanding over time)

- Ideal - an outcome that can never be obtained but can be approached without limit

- Purposeful choices come from perception, consciousness (the perception of the mental state of another or oneself), and memory

- Models are used because they are easier to manipulate than reality itself. This usually arises from the fact that the images and concepts that make up the models are usually easier to manipulate than is reality, and from their being usually simpler than reality

- An individual believes in the existence of things only when he believes they make a difference in his pursuit of his goals. Hence, any attempt to define what is meant by an individual's belief in the existence of a thing should make reference to the outcome that he seeks (to his purposeful state)

- Hypothesis - a belief (which has some doubt associated with it) in the past, present, or future existence of something that has never been perceived

- A purposeful individual has 3 different ways of disposing of a problem: dissolution, resolution, and solution

- An individual who has a problem can change his intentions so that his dissatisfaction dissolves. It is the removal (production of the subsequent absence) of a problem situation by a purposeful individual who is in it, by a change in that individual's intentions

- Resolution of a problem - the removal of a problem situation by a purposeful individual who is in it, by an arbitrary choice

- Solving a problem requires answering two questions - what alternatives are available and which one is best or good enough

- Thought is conscious inference. Intuition is unconscious inference

- The relation of instrumentality is inherent in the relation between a purposeful system and its purposeful elements. A system must be either variety increasing or variety decreasing

- Organisms and organizations are fundamentally different. Both organisms and organizations are purposeful systems, but organisms do not contain purposeful elements. The elements of an organism may be functional, goal-seeking, or multi-goal-seeking, but not purposeful. In an organism only the whole can display will; none of its parts can. Because an organism is a system that has a functional division of labor it can also be said to be organized. Its functionally distinct parts are called organs. Their functioning is necessary but not sufficient for accomplishment of the organism's purpose(s)

- Many wise men have observed that there is more satisfaction in pursuing an end than in attaining it; to play a game well yields more satisfaction than does winning it. Also, some have observed that the researcher's and manager's objective is not so much to solve problems as it is to create more challenging and important problems to work on by solving the one at hand. This is to say that the continuous pursuit of more desirable ends is an end in itself, and hence that the attainment of a specific end can be conceptualized as a means to such pursuit. Such observations suggest that a pervasive objective of man and the social systems of which he is a part is the successful pursuit of increasingly desirable objectives. If this is so, then it is reasonable for man and the social systems of which he is part to formulate objectives that can be pursued without end but can be continually approached. Man seeks objectives that enable him to convert the attainment of every goal into a means for the attainment of a new and more desirable goal. The ultimate objective in such a sequence cannot be obtainable; otherwise its attainment would put an end to the process. And end that satisfies these conditions is an ideal. Ideal pursuit can provide cohesiveness and continuity to extended and unpredictable processes, to life and history. Thus the formulation and pursuit of ideals is a means by which man puts meaning and significance into his life and into the history of which he is a part. It also provides the possibility of deriving satisfaction from a life that must end but that can contribute to a history that may not.

- The distinction between knowledge and wisdom is important. Knowledge is a means-oriented concept. Wisdom is end- as well as means-oriented. Knowledge is more common than wisdom.

What I got out of it

- Thought provoking book and exciting to go deeper on systems thinking and how you can apply it to your day to day life. The idea of dissolving a problem (rather than solving it) is enticing and vibes with the path of least resistance. The idea that organisms' various parts don't themselves have purpose but only the whole is important to remember, whereas the constituents of an organization each have their own purpose