- Progression

- That is no way to start a writing project, let me tell you. You begin with a subject, gather material, and work your way to structure from there. You pile up volumes of notes and then figure out what you are going to do with them, not the other way around

- Structure

- His role in life was huge. Quarter horses are much faster than Thoroughbreds, and a third of a minute after he opened the gate their quarter-mile races were over. A quarter horse had been clocked at fifty-five miles an hour, the world record for racehorses of any kind.

- In some twenty months, I had submitted a half dozen pieces, short and long, and the editor, William Shawn, had bought them all. You would think that by then I would have developed some confidence in writing a new story, but I hadn’t, and never would. To lack of confidence at the outset seems rational to me. It doesn’t matter that something you’ve done before worked out well. Your last piece is never going tow rite your next one for you. Square 1 does not become Square 2, just Square 1 squared and cubed.

- Structure has preoccupied me in every project I have undertaken since, and, like Mrs. McKee, I have hammered it at Princeton writing students across decades of teaching: “You can build a strong, sound, and artful structure. You can build a structure in such a way that it causes people to want to keep turning pages. A compelling structure in nonfiction can have an attracting effect analogous to a storyline in fiction.”

- Developing a structure is seldom that simple. Almost always there is considerable tension between chronology and theme, and chronology traditionally wins

- Readers are not supposed to notice the structure. It is meant to be about as visible as someone’s bones. And I hope this structure illustrates what it takes to be a basic criterion for all structures: they should not be imposed upon the material. They should arise from within it. That perfect circle was a help to me, but it could be a liability for anyone trying to impose such a thing on just any set of facts. A structure is not a cookie-cutter

- Often, after you have reviewed your notes many times and thought through your material, it is difficult to frame much of a structure until you write a lead. You wade around in your notes, getting nowhere. You don’t see a pattern. You don’t know what to do. So, stop everything. Stop looking at the notes. Hunt through your mind for a good beginning. Then write it. Write a lead. If the whole piece is not to e a long one, you may plunge right on and out the other side and have a finished draft before you know it; but if the piece is to have some combination of substance, complexity, and structural juxtaposition that pays dividends, you might begin with that acceptable and workable lead and then be able to sit back with the lead in hand and think about where you are going and how you plan to get there. Writing a successful lead, in other words, can illuminate the structure problem for you and cause you to see the piece whole – to see it conceptually, in various parts, to which you then assign your materials. You find your lead, you build your structure, you're now free to write. Some of these thoughts on leads, taken from my seminar notes, were printed several years ago in the World Craft column of The Wall Street Journal. In slightly altered form, I’m including them here. I would go so far as to suggest that you should always write your lead (redoing it and polishing it until you are satisfied that it will serve) before you go at the big pile of raw material and sort it into a structure.

- All leads – of every variety – should be sound. They should never promise what does not follow. You read an exciting action lead about a car chase up a narrow street. Then the article turns out to be a financial analysis of debt structures in private universities. You’ve been had. The lead – like the title – should be a flashlight that shines down into the story. A lead is a promise

- Another way to prime the pump is to write by hand. Keep a legal pad, or something like one, and when you are stuck dead at any time – blocked to paralysis by an inability to set one word upon another – get away from the computer, lie down somewhere with pencil and pad, and think it over. This can do wonders at any point in a piece and is especially helpful when you have written nothing at all. Sooner or later something comes to you. Without getting up, you roll over and scribble on the pad. Go on scribbling as long as the words develop. Then get up and copy what you have written into your computer file.

- Another mantra, which I still write in chalk on the blackboard, is “A Thousand Details Add Up to One Impression.” It’s actually a quote from Cary Grant. Its implication is that few (if any) details are individually essential, while the details collectively are absolutely essential. What to include, what to leave out. Those thoughts are with you from the start. While scribbling your notes in the field, you obviously leave out a great deal of what you’re looking at. Writing is selection, and the selection starts right there at Square 1.

- I’ve come to the end, but in all the drafts and revisions and substitutions of one word for another how do I know there is no more to do? When am I done? I just know. I’m lucky that way. What I know is that I can’t do any better; someone else might do better, but that’s all I can do; so, I call it done

- Editors and Publishers

- Shawn also recognized that no two writers are the same, like snowflakes and fingerprints. No one will ever write in just the way that you do, or in just the way that anyone else does. Because of this fact, there is no real competition between writers. What appears to be a competition is actually nothing more than jealousy and gossip. Writing is a matter strictly of developing oneself. You compete only with yourself. You are developing yourself by writing. An editor’s goal is to help writers make the most of the patterns that are unique about them.

- Elicitation

- Use a voice recorder, but maybe not as a first choice – more like a relief pitcher. Whatever you do, don’t rely on memory. Don’t even imagine that you will be able to remember verbatim in the evening what people said during the day. And don’t squirrel notes in a bathroom – that is, run off to the john and write surreptitiously what someone said back there with the cocktails. From the start, make clear what you are doing and who will publish what you write.

- If doing nothing can produce a useful reaction, so can the appearance of being dumb. You can develop a distinct advantage by waxing slow of wit. Evidently, you need help. Who is there to help you but the person who is answering your questions? The result is the opposite of the total shutdown that might have occurred had you appeared glib and omniscient.

- Students have always asked what I do to prepare for interviews. Candidly, not much. At minimum, though, I think you should do enough preparation to be polite

- Frame of Reference

- To sense the composite nature of frames of reference, think of their incidental aftermath, think of some old ones as they have moved through time, eventually forming distinct strata in history. At the University of Cambridge, academic supervisors in English literature would hand you a photocopy of an unidentified swatch of prose or poetry and ask you to say in what decade of what century it was written

- Nobody should ever be trying that. We should just be hoping that our pieces aren’t obsolete before the editor sees them. If you look for allusions and images that have some durability, your choices will stabilize your piece of writing. Don’t assume that everyone on earth has seen every movie you have seen.

- Draft No. 4

- She had a point. It isn’t all like that – only the first draft. First drafts are slow and develop clumsily because every sentence affects not only those before it but also those that follow. The first draft of my book on California geology took two gloomy years; the second, third, and fourth drafts took about six months altogether. That four-to-one ratio in writing time – first draft versus the other drafts combined – has for me been consistent in projects of any length, even if the first draft takes only a few days or weeks. There are psychological differences from phase to phase, and the first is the phase of the pit and the pendulum. After that, it seems as if a different person is taking over. Dread largely disappears. Problems become less threatening, more interesting. Experience is more helpful, as if an amateur is being replaced by a professional. Days go by quickly and not a few could be called pleasant, I’ll admit…What I have left out is the interstitial time. You finish that first awful thing, and then you put the thing aside. You get in your car and drive home. On the way, your mind is still knitting at the words. You think of a better way to say something, a good phrase to correct a certain problem. Without the drafted version – if it did not exist – you obviously would not be thinking of things that would improve it. In short, you may be actually writing only two or three hours a day, but your mind, in one way or another, is working on it twenty-four hours a day – yes, while you sleep – but only if some sort of draft or earlier version already exists. Until it exists, writing has not really begun.

- It is toward the end of the second draft, if I’m lucky, when the feeling comes over me that I have something I want to show to other people, something that seems to be working and is not going to go away. The feeling is more than welcome, but it is hardly euphoria. It’s just a new lease on life, a sense that I’m going to survive until the middle of next month. After reading the second draft aloud, and going through the piece for the third time (removing the tin horns and radio static that I heard while reading), I enclose words and phrases in penciled boxes for Draft No. 4. If I enjoy anything in this process it is Draft No. 4. I go searching for replacements for the words in the boxes. The final adjustments may be small-scale, but they are large to me, and I love addressing them…You draw a box not only around any word that does not seem quite right but also around words that fulfill their assignment but seem to present an opportunity. While the word inside the box may be perfectly ok, there is likely to be an even better word for this situation, a word right smack on the button, and why don’t you try to find such a word?

- Omission

- Writing is selection. Just to start a piece of writing you have to choose one word and only one from more than a million in the language. Now keep going. What is your next word? Your next sentence, paragraphs section, chapter? Your next ball of fact. You select what goes in and you decide what stays out. At base you have only one criterion: if something interests you, it goes in – if not, it stays out. That’s a crude way to assess things, but it’s all you’ve got. Forget market research. Never market-research your writing. Write on subjects in which you have enough interest on your own to see through all the stops, starts, hesitations, and other impediments along the way. Ideally, a piece of writing should grow to whatever length is sustained by its selected material – that much and no more.

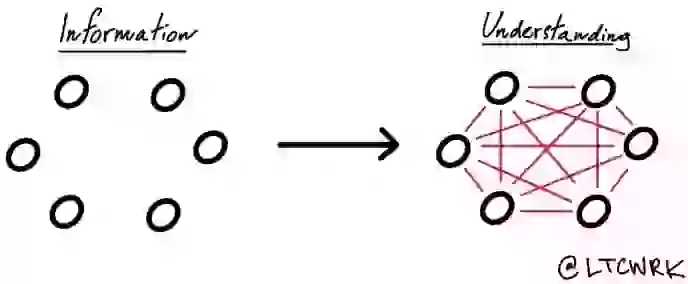

- Hemingway sometimes called the concept the Theory of Omission. In 1958, in an “Art of Fiction” interview for The Paris Review, he said to George Plimpton, “Anything you know you can eliminate, and it only strengthens your iceberg.” To illustrate, he said, “I’ve seen the marlin mate and know about that. So, I leave it out. I’ve seen a school (or pod) of more than fifty sperm whales in that same stretch of water and once harpooned one nearly sixty feet in length and lost him. So, I left that out. All the stories I know from the fishing village I leave out. But the knowledge is what makes the underwater part of the iceberg.” In other words, there are known knowns – there are things we know. We also know there are known unknowns. That is to say, we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know. Yes, the influence of Ernest Hemingway evidently extended to the Pentagon. Be that as it might not be, Ernest Hemingway’s Theory of Omission seems to me to be saying to writers, “Back off. Let the reader to the creating.” To cause a reader to see in her mind’s eye an entire autumnal landscape, for example, a writer need only deliver a few words and images – such as corn shocks, pheasants, and an early frost. the creative writer leaves white space between chapters or segments of chapters. The creative reader silently articulates the unwritten thought that is present in the white space. Let the reader have the experience. Leave the judgment in the eye of the beholder. When you are deciding what to leave out, begin with the author. If you see yourself prancing around between subject and reader, get lost. Give elbow room to the creative reader. In other words, to the extent that this is all about you, leave that out.

- Creative nonfiction is not making something up, but making the most of what you have

What I got out of it

- Some great tips from a legend in the field - it takes as long as it takes; writing is re-writing, writing is selection