- Frames

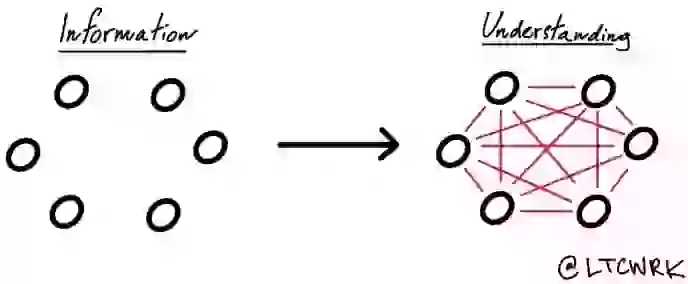

- Frames are mental structures that shape the way we see the world. As a result, they shape the goals we seek, the plans we make, the way we act, and what counts as a good or bad outcome of our actions.

- You can’t see or hear frames. They are part of what we cognitive scientists call the “cognitive unconscious”—structures in our brains that we cannot consciously access, but know by their consequences. What we call “common sense” is made up of unconscious, automatic, effortless inferences that follow from our unconscious frames.

- Not only does negating a frame activate that frame, but the more it is activated, the stronger it gets. The moral for political discourse is clear: When you argue against someone on the other side using their language and their frames, you are activating their frames, strengthening their frames in those who hear you, and undermining your own views. For progressives, this means avoiding the use of conservative language and the frames that the language activates.

- Because language activates frames, new language is required for new frames. Thinking differently requires speaking differently. Reframing is not easy or simple. It is not a matter of finding some magic words. Frames are ideas, not slogans. Reframing is more a matter of accessing what we and like-minded others already believe unconsciously, making it conscious, and repeating it till it enters normal public discourse. It doesn’t happen overnight. It is an ongoing process. It requires repetition and focus and dedication.

- Reframing without a system of communication accomplishes nothing. Reframing, as we discuss it in this book, is about honesty and integrity. It is the opposite of spin and manipulation. It is about bringing to consciousness the deepest of our beliefs and our modes of understanding. It is about learning to express what we really believe in a way that will allow those who share our beliefs to understand what they most deeply believe and to act on those beliefs.

- Framing is also about understanding those we disagree with most.

- Facts matter enormously, but to be meaningful they must be framed in terms of their moral importance. Remember, you can only understand what the frames in your brain allow you to understand. If the facts don’t fit the frames in your brain, the frames in your brain stay and the facts are ignored or challenged or belittled.

- This gives us a basic principle of framing: When you are arguing against the other side, do not use their language. Their language picks out a frame—and it won’t be the frame you want.

- When you think you just lack words, what you really lack are ideas. Ideas come in the form of frames. When the frames are there, the words come readily. There’s a way you can tell when you lack the right frames. There’s a phenomenon you have probably noticed. A conservative on TV uses two words, like tax relief. And the progressive has to go into a paragraph-long discussion of his own view. The conservative can appeal to an established frame, that taxation is an affliction or burden, which allows for the two-word phrase tax relief. But there is no established frame on the other side. You can talk about it, but it takes some doing because there is no established frame, no fixed idea already out there.

- The first mistake is believing that framing is a matter of coming up with clever slogans, like “death tax” or “partial-birth abortion,” that resonate with a significant segment of the population. Those slogans only work when there has been a long—often decades-long—campaign of framing issues like taxation and abortion conceptually, so that the brains of many people are prepared to accept those phrases.

- The second mistake is believing that, if only we could present the facts about a certain reality in some effective way, then people would “wake up“ to that reality, change their personal opinion, and start acting politically to change society. “Why can’t people wake up?” is the complaint—as if people are “asleep” and just have to be aroused to see and comprehend the world around them. But the reality is that certain ideas have to be ingrained in us—developed over time consistently and precisely enough to create an accurate frame for our understanding.

- Spin is the manipulative use of a frame. Spin is used when something embarrassing has happened or has been said, and it’s an attempt to put an innocent frame on it—that is, to make the embarrassing occurrence sound normal or good.

- Propaganda is another manipulative use of framing. Propaganda is an attempt to get the public to adopt a frame that is not true and is known not to be true, for the purpose of gaining or maintaining political control.

- If you remember nothing else about framing, remember this: Once your frame is accepted into the discourse, everything you say is just common sense. Why? Because that’s what common sense is: reasoning within a commonplace, accepted frame.

- A useful thing to do is to use rhetorical questions: Wouldn’t it be better if . . . ? Such a question should be chosen to presuppose your frame. Examples: Wouldn’t it be better if we could fix the potholes in the roads and the bridges that are crumbling? Or, wouldn’t we all be better off if everybody with diseases and illnesses could be treated so that diseases and illnesses wouldn’t spread? Or, wouldn’t it be better if all kids were ready for school when they went to kindergarten?

- Always start with values, preferably values all Americans share such as security, prosperity, opportunity, freedom, and so on. Pick the values most relevant to the frame you want to shift to. Try to win the argument at the values level.

- Those are a lot of guidelines. But there are only four really important ones: Show respect, Respond by reframing, Think and talk at the level of values, Say what you believe

- Other

- In fact, about 98 percent of what our brains are doing is below the level of consciousness. As a result, we may not know all, or even most, of what in our brains determines our deepest moral, social, and political beliefs. And yet we act on the basis of those largely unconscious beliefs.

- People do not necessarily vote in their self-interest. They vote their identity. They vote their values. They vote for who they identify with. This is very important to understand. The goal is to activate your model in the people in the “middle.” The people who are in the middle have both models, used regularly in different parts of their lives. What you want to do is to get them to use your model for politics—to activate your worldview and moral system in their political decisions. You do that by talking to people using frames based on your worldview.

- Orwellian language points to weakness—Orwellian weakness. When you hear Orwellian language, note where it is, because it is a guide to where they are vulnerable. They do not use it everywhere. It is very important to notice this and use their weakness to your advantage.

- Levy addressed the question of why there were so many suicides in Tahiti, and discovered that Tahitians did not have a concept of grief. They felt grief. They experienced it. But they did not have a concept for it or a name for it. They did not see it as a normal emotion. There were no rituals around grief. No grief counseling, nothing like it. They lacked a concept they needed—and wound up committing suicide all too often.

- The truth alone will not set you free. Just speaking truth to power doesn’t work. You need to frame the truths effectively from your perspective.

- Accordingly, the frame-inherent world, structured by our framed actions, reinforces those frames and recreates those frames in others as they are born, grow, and mature in such a world. This phenomenon is called reflexivity. The world reflects our understandings through our actions, and our understandings reflect the world shaped by the frame-informed actions of ourselves and others. To function effectively in the world it helps to be aware of reflexivity. It helps to be aware of what frames have shaped and are still shaping reality if you are going to intervene to make the world a better place.

- Studying cognitive linguistics has its uses. Every language in the world has in its grammar a way to express direct causation. No language in the world has in its grammar a way to express systemic causation.

- Systemic causation has a structure—four possible elements that can exist alone or in combination.

- A network of direct causes.

- Feedback loops.

- Multiple causes.

- Probabilistic causation.

- Empathy and sympathy both involve the capacity to know what others are feeling. But unlike empathy, sympathy involves distancing, overriding personal emotional feeling. Someone who is sympathetic may well act to relieve the pain of others but not feel the pain themselves. The word “compassion” can be used for either empathy or sympathy, depending on who is using the word.

- Colin Powell had always argued that no troops should be committed without specific objectives, a clear and achievable definition of victory, and a clear exit strategy, and that open-ended commitments should not be used.

- Tell a story. Find stories where your frame is built into the story. Build up a stock of effective stories.

What I got out of it

- Didn't realize it was a political book, but some of the core ideas about how and why to effectively frame things was helpful