-

Background & Fundamentals of Crossing the Chasm

-

It is only natural to cling to the past when the past represents so much of what we have strived to achieve. This is the key to Crossing the Chasm. The chasm represents the gulf between two distinct marketplaces for technology products—the first, an early market dominated by early adopters and insiders who are quick to appreciate the nature and benefits of the new development, and the second a mainstream market representing “the rest of us,” people who want the benefits of new technology but who do not want to “experience” it in all its gory details. The transition between these two markets is anything but smooth. Indeed, what Geoff Moore has brought into focus is that, at the time when one has just achieved great initial success in launching a new technology product, creating what he calls early market wins, one must undertake an immense effort and radical transformation to make the transition into serving the mainstream market. This transition involves sloughing off familiar entrepreneurial marketing habits and taking up new ones that at first feel strangely counterintuitive.

-

The basic forces don’t change, but the tactics have become more complicated. Moreover, we are seeing a new effect which was just barely visible in the prior decade, the piggybacking of one company’s offer on another to skip the chasm entirely and jump straight into hypergrowth. In the 1980s Lotus piggybacked on VisiCalc to accomplish this feat in the spreadsheet category. In the 1990s Microsoft has done the same thing to Netscape in browsers. The key insight here is that we should always be tracking the evolution of a technology rather than a given company’s product line—it’s the Technology Adoption Life Cycle, after all. Thus it is spreadsheets, not VisiCalc, Lotus, or Excel, that is the adoption category, just as it is browsers, not Navigator or Explorer. In the early days products and categories were synonymous because technologies were on their first cycles. But today we have multiple decades of invention to build on, and a new offer is no longer quite as new or unprecedented as it used to be.

-

If we step back from this chasm problem, we can see it as an instance of the larger problem of how the marketplace can cope with change in general. For both the customer and the vendor, continually changing products and services challenge their institution’s ability to absorb and make use of the new elements. What can marketing do to buffer these shocks? Fundamentally, marketing must refocus away from selling product and toward creating relationships. Relationship buffers the shock of change. Marketing’s first deliverable is that partnership. This is what we mean when we talk about “owning a market.” Customers do not like to be “owned,” if that implies lack of choice or freedom. The open systems movement in high tech is a clear example of that. But they do like to be “owned” if what that means is a vendor taking ongoing responsibility for the success of their joint ventures. Ownership in this sense means abiding commitment and a strong sense of mutuality in the development of the marketplace. When customers encounter this kind of ownership, they tend to become fanatically loyal to their supplier, which in turn builds a stable economic base for profitability and growth.

-

The fundamental requirement for the ongoing, interoperability needed to sustain high tech is accurate and honest exchange of information. Your partners need it, your distribution channel needs it and must support it, and your customers demand it.

-

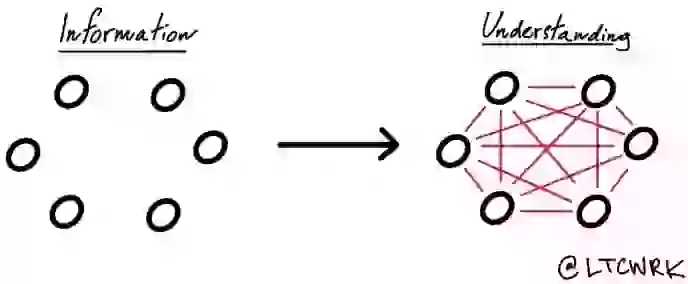

The fundamental basis of market relations is to build and manage relationships with all the members that make up a high-tech marketplace, not just the most visible ones. In particular, it means setting up formal and informal communications not only with customers, press, and analysts but also with hardware and software partners, distributors, dealers, VARs, systems and integrators, user groups, vertically oriented industry organizations, universities, standards bodies, and international partners. It means improving not only your external communications but also your internal exchange of information among the sales force, the product managers, strategic planners, customer service and support, engineering, manufacturing, and finance.

-

Must see through every stakeholder's eyes and create win-win relationships. This becomes even more complicated with public, high-tech companies given the number of constituents

-

-

The problem, since these techniques are antithetical to each other, is that you need to decide which one - fad or trend - you are dealing with before you start. It would be much better if you could start with a fad, exploit it for all it was worth, and then turn it into a trend. That may seem like a miracle, but that is in essence what high-tech marketing is all about. Every truly innovative high-tech product starts out as a fad—something with no known market value or purpose but with “great properties” that generate a lot of enthusiasm within an “in crowd.” That’s the early market. Then comes a period during which the rest of the world watches to see if anything can be made of this; that is the chasm. If in fact something does come out of it—if a value proposition is discovered that can predictably be delivered to a targetable set of customers at a reasonable price-then a new mainstream market forms, typically with a rapidity that allows its initial leaders to become very, very successful. The key in all this is crossing the chasm—making that mainstream market emerge. This is a do-or-die proposition for high-tech enterprises; hence, it is logical that they be the crucible in which “chasm theory” is formed.

-

The rule of thumb in crossing the chasm is simple: Pick on somebody your own size.

-

These are the two “natural” marketing rhythms in high tech— developing the early market and developing the mainstream market. You develop an early market by demonstrating a strong technology advantage and converting it to product credibility, and you develop a mainstream market by demonstrating a market leadership advantage and converting it to company credibility. By contrast, the “chasm transition” represents an unnatural rhythm. Crossing the chasm requires moving from an environment of support among the visionaries back into one of skepticism among the pragmatists. It means moving from the familiar ground of product-oriented issues to the unfamiliar ground of market-oriented ones, and from the familiar audience of like-minded specialists to the unfamiliar audience of essentially uninterested generalists.

-

Market Development Strategy Checklist. This list consists of a set of issues around which go-to-market plans are built, each of which incorporates a chasm-crossing factor, as follows:

-

Target customer

-

Compelling reason to buy

-

Whole product

-

Partners and allies

-

Distribution

-

Pricing

-

Competition

-

Positioning

-

Next target customer

-

-

-

Technology Adoption Life Cycle - The Cause for the Chasm

-

To recap the logic of the Technology Adoption Life Cycle, its underlying thesis is that technology is absorbed into any given community in stages corresponding to the psychological and social profiles of various segments within that community. This profile, is in turn, the very foundation of the High-Tech Marketing Model. That model says that the way to develop a high-tech market is to work the curve left to right, focusing first on the innovators, growing that market, then moving on to the early adopters, growing that market, and so on, to the early majority, late majority, and even to the laggards. In this effort, companies must use each “captured” group as a reference base for going on to market to the next group. Thus, the endorsement of innovators becomes an important tool for developing a credible pitch to the early adopters, that of the early adopters to the early majority, and so on. The idea is to keep this process moving smoothly, proceeding something like passing the baton in a relay race or imitating Tarzan swinging from vine to well-placed vine. It is important to maintain momentum in order to create a bandwagon effect that makes it natural for the next group to want to buy in. Too much of a delay and the effect would be something like hanging from a motionless vine—nowhere to go but down. As you can see, the components of the life cycle are unchanged, but between any two psychographic groups has been introduced a gap. This symbolizes the dissociation between the two groups—that is, the difficulty any group will have in accepting a new product if it is presented in the same way as it was to the group to its immediate left. Each of these gaps represents an opportunity for marketing to lose momentum, to miss the transition to the next segment, thereby never to gain the promised land of profit-margin leadership in the middle of the bell curve. The key to winning over this segment is to show that the new technology enables some strategic leap forward, something never before possible, which has an intrinsic value and appeal to the nontechnologist. This benefit is typically symbolized by a single, compelling application, the one thing that best captures the power and value of the new product. If the marketing effort is unable to find that compelling application, then market development stalls with the innovators, and the future of the product falls through the crack.

-

It turns out our attitude toward technology adoption becomes significant—at least in a marketing sense—any time we are introduced to products that require us to change our current mode of behavior or to modify other products and services we rely on. In academic terms, such change-sensitive products are called discontinuous innovations. The contrasting term, continuous innovations, refers to the normal upgrading of products that does not require us to change behavior.

-

Of course, talking this way about marketing merely throws the burden of definition onto market, which we will define, for the purposes of high tech, as:

-

A set of actual or potential customers

-

For a given set of products or services

-

Who have a common set of needs or wants

-

Who reference each other when making a buying decision.

-

-

The goal should be to package each of the phases such that each phase

-

Is accomplishable by mere mortals working in earth time

-

Provides the vendor with a marketable product

-

Provides the customer with a concrete return on investment that can be celebrated as a major step forward.

-

-

-

-

Innovators

-

Visionaries are not looking for an improvement; they are looking for a fundamental breakthrough.

-

In sum, visionaries represent an opportunity early in a product’s life cycle to generate a burst of revenue and gain exceptional visibility.

-

-

Early Adopters

-

What the early adopter is buying is some kind of change agent. By being the first to implement this change in their industry, the early adopters expect to get a jump on the competition, whether from lower product costs, faster time to market, more complete customer service, or some other comparable business advantage. They expect a radical discontinuity between the old ways and the new, and they are prepared to champion this cause against entrenched resistance. Being the first, they also are prepared to bear with the inevitable bugs and glitches that accompany any innovation just coming to market.

-

-

Early Majority (Pragmatists)

-

The real news, however, is not the two cracks in the bell curve, the one between the innovators and the early adopters, the other between the early and late majority. No, the real news is the deep and dividing chasm that separates the early adopters from the early majority. This is by far the most formidable and unforgiving transition in the Technology Adoption Life Cycle, and it is all the more dangerous because it typically goes unrecognized. The reason the transition can go unnoticed is that with both groups the customer list and the size of the order can look the same.

-

The early majority want to buy a productivity improvement for existing operations. They are looking to minimize the discontinuity with the old ways. They want evolution, not revolution. They want technology to enhance, not overthrow, the established ways of doing business. And above all, they do not want to debug somebody else’s product. By the time they adopt it, they want it to work properly and to integrate appropriately with their existing technology base. This contrast just scratches the surface relative to the differences and incompatibilities among early adopters and the early majority. Let me just make two key points for now: Because of these incompatibilities, early adopters do not make good references for the early majority. And because of the early majority’s concern not to disrupt their organizations, good references are critical to their buying decisions. So what we have here is a catch-22. The only suitable reference for an early majority customer, it turns out, is another member of the early majority, but no upstanding member of the early majority will buy without first having consulted with several suitable references.

-

Of course, to market successfully to pragmatists, one does not have to be one—just understand their values and work to serve them. To look more closely into these values, if the goal of visionaries is to take a quantum leap forward, the goal of pragmatists is to make a percentage improvement—incremental, measurable, predictable progress. If they are installing a new product, they want to know how other people have fared with it. The word risk is a negative word in their vocabulary—it does not connote opportunity or excitement but rather the chance to waste money and time.

-

If pragmatists are hard to win over, they are loyal once won, often enforcing a company standard that requires the purchase of your product, and only your product, for a given requirement. This focus on standardization is, well, pragmatic, in that it simplifies internal service demands. But the secondary effects of this standardization—increasing sales volumes and lowering the cost of sales—is dramatic. Hence the importance of pragmatists as a market segment.

-

When pragmatists buy, they care about the company they are buying from, the quality of the product they are buying, the infrastructure of supporting products and system interfaces, and the reliability of the service they are going to get. In other words, they are planning on living with this decision personally for a long time to come.

-

Pragmatists won’t buy from you until you are established, yet you can’t get established until they buy from you. Obviously, this works to the disadvantage of start-ups and, conversely, to the great advantage of companies with established track records. On the other hand, once a start-up has earned its spurs with the pragmatist buyers within a given vertical market, they tend to be very loyal to it, and even go out of their way to help it succeed. When this happens, the cost of sales goes way down, and the leverage on incremental R&D to support any given customer goes way up. That’s one of the reasons pragmatists make such a great market.

-

Overall, to market to pragmatists, you must be patient. You need to be conversant with the issues that dominate their particular business. You need to show up at the industry-specific conferences and trade shows they attend. You need to be mentioned in articles that run in the magazines they read. You need to be installed in other companies in their industry. You need to have developed applications for your product that are specific to the industry. You need to have partnerships and alliances with the other vendors who serve their industry. You need to have earned a reputation for quality and service. In short, you need to make yourself over into the obvious supplier of choice. This is a long-term agenda, requiring careful pacing, recurrent investment, and a mature management team

-

Conservatives like to buy preassembled packages, with everything bundled, at a heavily discounted price. The last thing they want to hear is that the software they just bought doesn’t support the printer they have installed. They want high-tech products to be like refrigerators—you open the door, the light comes on automatically, your food stays cold, and you don’t have to think about it. The products they understand best are those dedicated to a single function—word processors, calculators, copiers, and fax machines. The notion that a single computer could do all four of these functions does not excite them—instead, it is something they find vaguely nauseating. The conservative marketplace provides a great opportunity, in this regard, to take low-cost, trailing-edge technology components and repackage them into single-function systems for specific business needs. The quality of the package should be quite high because there is nothing in it that has not already been thoroughly debugged. The price should be quite low because all the R&D has long since been amortized, and every bit of the manufacturing learning curve has been taken advantage of. It is, in short, not just a pure marketing ploy but a true solution for a new class of customer. There are two keys to success here. The first is to have thoroughly thought through the “whole solution” to a particular target end user market’s needs, and to have provided for every element of that solution within the package. This is critical because there is no profit margin to support an afterpurchase support system. The other key is to have lined up a low-overhead distribution channel that can get this package to the target market effectively.

-

Just as the visionaries drive the development of the early market, so do the pragmatists drive the development of the mainstream market. Winning their support is not only the point of entry but the key to long-term dominance. But having done so, you cannot take the market for granted. To maintain leadership in a mainstream market, you must at least keep pace with the competition. It is no longer necessary to be the technology leader, nor is it necessary to have the very best product. But the product must be good enough, and should a competitor make a major breakthrough, you have to make at least a catch-up response.

-

The key to making a smooth transition from the pragmatist to the conservative market segments is to maintain a strong relationship with the former, always giving them an open door to go to the new paradigm, while still keeping the latter happy by adding value to the old infrastructure. It is a balancing act to say the least, but properly managed the earnings potential in loyal mature market segments is very high indeed.

-

So the corollary lesson is, we must use our experience with the pragmatist customer segment to identify all the issues that require service and then design solutions to these problems directly into the product.

-

In sum, the pragmatists are loath to buy until they can compare. Competition, therefore, becomes a fundamental condition for purchase. So, coming from the early market, where there are typically no perceived competing products, with the goal of penetrating the mainstream, you often have to go out and create your competition. Creating the competition is the single most important marketing decision made in the battle to enter the mainstream. It begins with locating your product within a buying category that already has some established credibility with the pragmatist buyers. That category should be populated with other reasonable buying choices, ideally ones with which the pragmatists are already familiar. Within this universe, your goal is to position your product as the indisputably correct buying choice.

-

In sum, to the pragmatist buyer, the most powerful evidence of leadership and likelihood of competitive victory is market share. In the absence of definitive numbers here, pragmatists will look to the quality and number of partners and allies you have assembled in your camp, and their degree of demonstrable commitment to your cause.

-

-

Late Majority

-

Simply put, the early majority is willing and able to become technologically competent, where necessary; the late majority, much less so. When a product reaches this point in the market development, it must be made increasingly easier to adopt in order to continue being successful. If this does not occur, the transition to the late majority may well stall or never happen.

-

-

Laggards

-

Skeptics—the group that makes up the last one-sixth of the Technology Adoption Life Cycle—do not participate in the high-tech marketplace, except to block purchases. Thus, the primary function of high-tech marketing in relation to skeptics is to neutralize their influence. In a sense, this is a pity because skeptics can teach us a lot about what we are doing wrong

-

-

-

The D-Day Strategy - Choose a Target Niche

-

Entering the mainstream market is an act of aggression. The companies who have already established relationships with your target customer will resent your intrusion and do everything they can to shut you out. The customers themselves will be suspicious of you as a new and untried player in their marketplace. No one wants your presence. You are an invader. This is not a time to focus on being nice. As we have already said, the perils of the chasm make this a life-or-death situation for you. You must win entry to the mainstream, despite whatever resistance is posed. That’s it. That’s the strategy. Replicate D Day, and win entry to the mainstream. Cross the chasm by targeting a very specific niche market where you can dominate from the outset, force your competitors out of that market niche, and then use it as a base for broader operations. Concentrate an overwhelmingly superior force on a highly focused target. It worked in 1944 for the Allies, and it has worked since for any number of high-tech companies.

-

The D-Day strategy prevents this mistake. It has the ability to galvanize an entire enterprise by focusing it on a highly specific goal that is (1) readily achievable and (2) capable of being directly leveraged into long-term success. Most companies fail to cross the chasm because, confronted with the immensity of opportunity represented by a mainstream market, they lose their focus, chasing every opportunity that presents itself, but finding themselves unable to deliver a salable proposition to any true pragmatist buyer. The D-Day strategy keeps everyone on point—if we don’t take Normandy, we don’t have to worry about how we’re going to take Paris. And by focusing our entire might on such a small territory, we greatly increase our odds of immediate success.

-

This isn’t rocket science, but it does represent a kind of discipline. And it is here that high-tech management shows itself most lacking. Most high-tech leaders, when it comes down to making marketing choices, will continue to shy away from making niche commitments, regardless. Like marriage-averse bachelors, they may nod in all the right places and say all the right things, but they will not show up when the wedding bells chime.

-

“Never attack a fortified hill.” Same with beachheads. If some other company got there before you, all the market dynamics that you are seeking to make work in your favor are already working in its favor. Don’t go there.

-

-

One of the most important lessons about crossing the chasm is that the task ultimately requires achieving an unusual degree of company unity during the crossing period. This is a time when one should forgo the quest for eccentric marketing genius, in favor of achieving an informed consensus among mere mortals. It is a time not for dashing and expensive gestures but rather for careful plans and cautiously rationed resources—a time not to gamble all on some brilliant coup but rather to focus everyone on making as few mistakes as possible. One of the functions of this book, therefore-and perhaps its most important one-is to open up the logic of marketing decision making during this period so that everyone on the management team can participate in the marketing process. If prudence rather than brilliance is to be our guiding principle, then many heads are better than one. If marketing is going to be the driving force-and most organizations insist this is their goal—then its principles must be accessible to all the players, and not, as is sometimes the case, be reserved to an elect few who have managed to penetrate its mysteries.

-

The consequences of being sales-driven during the chasm period are, to put it simply, fatal.

-

Segment. Segment. Segment. One of the other benefits of this approach is that it leads directly to you “owning” a market. That is, you get installed by the pragmatists as the leader, and from then on, they conspire to help keep you there. This means that there are significant barriers to entry for any competitors, regardless of their size or the added features they have in their product. Mainstream customers will, to be sure, complain about your lack of features and insist you upgrade to meet the competition. But, in truth, mainstream customers like to be “owned”—it simplifies their buying decisions, improves the quality and lowers the cost of whole product ownership, and provides security that the vendor is here to stay. They demand attention, but they are on your side. As a result, an owned market can take on some of the characteristics of an annuity—a building block in good times, and a place of refuge in bad—with far more predictable revenues and far lower cost of sales than can otherwise be achieved.

-

For all these reasons—for whole product leverage, for word-of-mouth effectiveness, and for perceived market leadership—it is critical that, when crossing the chasm, you focus exclusively on achieving a dominant position in one or two narrowly bounded market segments. If you do not commit fully to this goal, the odds are overwhelmingly against your ever arriving in the mainstream market.

-

The key to moving beyond one’s initial target niche is to select strategic target market segments to begin with. That is, target a segment that, by virtue of its other connections, creates an entry point into a larger segment. For example, when the Macintosh crossed the chasm, the target niche was the graphics arts department in Fortune 500 companies. This was not a particularly large target market, but it was one that was responsible for a broken, mission-critical process—providing presentations for executives and marketing professionals.

-

The niche wins—presuming the beachhead strategy is conducted correctly—by getting a fix for its specialized problem. And the vendor wins because it gets certified by at least one group of pragmatists that its offering is mainstream. So, because of the dynamics of technology adoption, and not because of any niche properties in the product itself, platforms must take a vertical market approach to crossing the chasm even though it seems unnatural.

-

The answer is that when you are picking a chasm-crossing target it is not about the number of people involved, it is about the amount of pain they are causing. In the case of the pharmaeutical industry’s regulatory affairs function, the pain was excruciating.

-

This is a standard pattern in crossing the chasm. It is normally the departmental function who leads (they have the problem), the executive function who prioritizes (the problem is causing enterprise-wide grief), and the technical function that follows (they have to make the new stuff work while still maintaining all the old stuff).

-

The more serious the problem, the faster the target niche will pull you out of the chasm. Once out, your opportunities to expand into other niches are immensely increased because now, having one set of customers solidly behind you, you are much less risky to back as a new vendor.

-

-

Next Target Segment

-

The second key is to have lined up other market segments into which you can leverage your initial niche solution. This allows you to reinterpret the financial gain in crossing the chasm. It is not about the money you make from the first niche: It is the sum of that money plus the gains from all subsequent niches. It is a bowling alley estimate, not just a head pin estimate, that should drive the calculation of gain.

-

First you divide up the universe of possible customers into market segments. Then you evaluate each segment for its attractiveness. After the targets get narrowed down to a very small number, the “finalists,” then you develop estimates of such factors as the market niches’ size, their accessibility to distribution, and the degree to which they are well defended by competitors.

-

Now, the biggest mistake one can make in this state is to turn to numeric information as a source of refuge or reassurance. You need to understand that informed intuition, rather than analytical reason, is the most trustworthy decision-making tool to use. The key is to understand how intuition—specifically, informed intuition—actually works. Unlike numerical analysis, it does not rely on processing a statistically significant sample of data in order to achieve a given level of confidence. Rather, it involves conclusions based on isolating a few high-quality images—really, data fragments—that it takes to be archetypes of a broader and more complex reality. These images simply stand out from the swarm of mental material that rattles around in our heads. They are the ones that are memorable. So the first rule of working with an image is: If you can’t remember it, don’t try, because it’s not worth it. Or, to put this in the positive form: Only work with memorable images.

-

Target-customer characterization is a formal process for making up these images, getting them out of individual heads and in front of a marketing decision-making group. The idea is to create as many characterizations as possible, one for each different type of customer and application for the product. (It turns out that, as these start to accumulate, they begin to resemble one another so that, somewhere between 20 and 50, you realize you are just repeating the same formulas with minor tweaks, and that in fact you have outlined 8 to 10 distinct alternatives.)

-

It is extremely difficult to cross the chasm in consumer market. Almost all successful crossings happen in business markets, where the economic and technical resources can absorb the challenges of an immature product and service offering.

-

The elements you need to capture are five:

-

Scene or situation: Focus on the moment of frustration. What is going on? What is the user about to attempt?

-

Desired outcome: What is the user trying to accomplish? Why is this important?

-

Attempted approach: Without the new product, how does the user go about the task?

-

Interfering factors: What goes wrong? How and why does it go wrong?

-

Economic consequences: So what? What is the impact of the user failing to accomplish the task productively?

-

-

-

Whole Product Package

-

Systems integrators could just as easily be called whole product providers—that is their commitment to the customer.

-

The whole product model provides a key insight into the chasm phenomenon. The single most important difference between early markets and mainstream markets is that the former are willing to take responsibility for piecing together the whole product (in return for getting a jump on their competition), whereas the latter are not.

-

Tactical alliances have one and only one purpose: to accelerate the formation of whole product infrastructure within a specific target market segment. The basic commitment is to codevelop a whole product and market it jointly. This benefits the product manager by ensuring customer satisfaction. It benefits the partner by providing expanded distribution into a hitherto untapped source of sales opportunities.

-

To sum up, whole product definition followed by a strong program of tactical alliances to speed the development of the whole product infrastructure is the essence of assembling an invasion force for crossing the chasm. The force itself is a function of actually delivering on the customer’s compelling reason to buy in its entirety. That force is still rare in the high-tech marketplace, so rare that, despite the overall high-risk nature of the chasm period, any company that executes a whole product strategy competently has a high probability of mainstream market success.

-

Review the whole product from each participant’s point of view. Make sure each vendor wins, and that no vendor gets an unfair share of the pie. Inequities here, particularly when they favor you, will instantly defeat the whole product effort—companies are naturally suspicious of each other anyway, and given any encouragement, will interpret your entire scheme as a rip-off.

-

The fundamental rule of engagement is that any force can defeat any other force—if it can define the battle. If we get to set the turf, if we get to set the competitive criteria for winning, why would we ever lose? The answer, depressingly enough, is because we don’t do it right. Sometimes it is because we misunderstand either our own strengths and weaknesses, or those of our competitors. More often, however, it is because we misinterpret what our target customers really want, or we are afraid to step up to the responsibility of making sure they get it.

-

-

Distribution

-

The number-one corporate objective, when crossing the chasm, is to secure a channel into the mainstream market with which the pragmatist customer will be comfortable.

-

In other words, during the chasm period, the number-one concern of pricing is not to satisfy the customer or to satisfy the investors, but to motivate the channel.

-

To sum up, when crossing the chasm, we are looking to attract customer-oriented distribution, and one of our primary lures will be distribution-oriented pricing.

-

When functioning at its best, within the limits just laid out, direct sales is the optimal channel for high tech. It is also the best channel for crossing the chasm.

-

All other things being equal, however, direct sales is the preferred alternative because it gives us maximum control over our own destiny.

-

First and foremost, the retail system works optimally when its job is to fulfill demand rather than to create it.

-

-

Positioning

-

To sum up, your market alternative helps people identify your target customer (what you have in common) and your compelling reason to buy (where you differentiate). Similarly, your product alternative helps people appreciate your technology leverage (what you have in common) and your niche commitment (where you differentiate). Thus you create the two beacons that triangulate to teach the market your positioning.

-

You can keep yourself from making most positioning gaffes if you will simply remember the following principles:

-

Positioning, first and foremost, is a noun, not a verb. That is, it is best understood as an attribute associated with a company or a product, and not as the marketing contortions that people go through to set up that association.

-

Positioning is the single largest influence on the buying decision. It serves as a kind of buyers’ shorthand, shaping not only their final choice but even the way they evaluate alternatives leading up to that choice. In other words, evaluations are often simply rationalizations of preestablished positioning.

-

Positioning exists in people’s heads, not in your words. If you want to talk intelligently about positioning, you must frame a position in words that are likely to actually exist in other people’s heads, and not in words that come straight out of hot advertising copy.

-

People are highly conservative about entertaining changes in positioning. This is just another way of saying that people do not like you messing with the stuff that is inside their heads. In general, the most effective positioning strategies are the ones that demand the least amount of change.

-

-

Given all of the above, it is then possible to talk about positioning as a verb—a set of activities designed to bring about positioning as a noun. Here there is one fundamental key to success: When most people think of positioning in this way, they are thinking about how to make their products easier to sell. But the correct goal is to make them easier to buy. Think about it, most people resist selling but enjoy buying. By focusing on making a product easy to buy, you are focusing on what the customers really want. In turn, they will sense this and reward you with their purchases. Thus, easy to buy becomes easy to sell. The goal of positioning, therefore, is to create a space inside the target customer’s head called “best buy for this type of situation” and to attain sole, undisputed occupancy of that space. Only then, when the green light is on, and there is no remaining competing alternative, is a product easy to buy.

-

-

Pricing

-

Set pricing at the market leader price point, thereby reinforcing your claims to market leadership (or at least not undercutting them), and build a disproportionately high reward for the channel into the price margin, a reward that will be phased out as the product becomes truly established in the mainstream, and competition for the right to distribute it increases.

-

-

Other

-

So how can we guarantee passing the elevator pitch test? The key is to define your position based on the target segment you intend to dominate and the value proposition you intend to dominate it with. Within this context, you then set forth your competition and the unique differentiation that belongs to you and that you expect to drive the buying decision your way. Here is a proven formula for getting all this down into two short sentences. Try it out on your own company and one of its key products. Just fill in the blanks:

-

For (target customers—beachhead segment only) who are dissatisfied with (the current market alternative), our product is a (new product category) that provides (key problem-solving capability). unlike (the product alternative), we have assembled (key whole product features for your specific application).

-

-

So building relationships with business press editors, initially around a whole product story, is a key tactic in crossing the chasm.

-

The purpose of the postchasm enterprise is to make money. This is a much more radical statement than it appears. To begin with, we need to recognize that this is not the purpose of the prechasm organization. In the case of building an early market, the fundamental return on investment is the conversion of an amalgam of technology, services, and ideas into a replicable, manufacturable product and the proving out that there is some customer demand for this product. Early market revenues are the first measure of this demand, but they are typically not—nor are they expected to be-a source of profit.

-

How wide is the chasm? Or, to put this in investment terms, how long will it take before I can achieve a reasonably predictable ROI from an acceptably large mainstream market? The simple answer to this question is, as long as it takes to create and install a sustainable whole product. The chasm model asserts that no mainstream market can occur until the whole product is in place.

-

The key is to initiate the transition by introducing two new roles during the crossing-the-chasm effort. The first of these might be called the target market segment manager, and the second, the whole product manager. Both are temporary, transitional positions, with each being a stepping stone to a more traditional role. Specifically, the former leads to being an industry marketing manager, and the latter to a product marketing manager. These are their “real titles,” the ones under which they are hired, the ones that are most appropriate for their business cards. But during the chasm transition they should be assigned unique, one-time-only responsibilities, and while they are in that mode, we will use their “interim” titles. The target market segment manager has one goal in his or her short job life—to transform a visionary customer relationship into a potential beachhead for entry into the mainstream vertical market that particular customer participates

-

-

Awesome playbook for building out a high-tech company and framework for how to invest in them (see The Gorilla Game for further notes on the investing portion). The innovators gladly take on new technology but it is the pragmatists or the early majority who need proof of concept, who need evidence that you will be around for a while and that other respected players are using your product or service before they buy in, and they are where the real profits lie. The chasm is formed between these innovators and pragmatists and your strategy, focus, and mindset has to shift when attempting to tap into the mainstream.