Key Takeaways.

- Finally, these two pieces coalesced—and evolved—into the present book, which explores the relationship between the technologies of the gambling industry and the experience of gambling addiction.

- The thing people never understand is that I’m not playing to win.” Why, then, does she play? “To keep playing—to stay in that machine zone where nothing else matters.”

- The French sociologist Roger Caillois, author of Man, Play, and Games, believed that games carried clues to the basic character of a culture. “It is not absurd to try diagnosing a civilization in terms of the games that are especially popular there,” he wrote in 1958. Caillois argued that one could make a cultural diagnosis by examining games’ combination of the following four elements of play: agon, or competition; alea, or chance; mimesis, or simulation; and ilinx, or vertigo. Modern cultures, he claimed, were distinguished by games involving a tension between agon and alea—the former demanding an assertion of will, the latter demanding surrender to chance.

- Goffman regarded gambling as the occasion for “character contests” in which players could demonstrate their courage, integrity, and composure in the face of contingency. By offering individuals the opportunity for heroic engagements with fate, gambling fulfilled an existential need for “action” or consequential activity in an increasingly bureaucratic society that deprived its citizens of the opportunity to express their character in public settings of risk. For Goffman, gambling was not so much an escape from everyday life as it was a bounded arena that mimicked “the structure of real-life,” thereby “immersing [players] in a demonstration of its possibilities.”

- The less predictable the outcome of a match, he observed, the more financially and personally invested participants became and the “deeper” their play, in the sense that its stakes went far beyond material gain or loss.

- machine gambling is not a symbolically profound, richly dimensional space whose “depth” can be plumbed to reveal an enactment of larger social and existential dramas. Instead, the solitary, absorptive activity can suspend time, space, monetary value, social roles, and sometimes even one’s very sense of existence. “You can erase it all at the machines—you can even erase yourself,” an electronics technician named Randall told me. Contradicting the popular understanding of gambling as an expression of the desire to get “something for nothing,” he claimed to be after nothingness itself. As Mollie put it earlier, the point is to stay in a zone “where nothing else matters.”

- As machine gamblers tell it, neither control, nor chance, nor the tension between the two drives their play; their aim is not to win but simply to continue.

- Although interactive consumer devices are typically associated with new choices, connections, and forms of self-expression, they can also function to narrow choices, disconnect, and gain exit from the self.

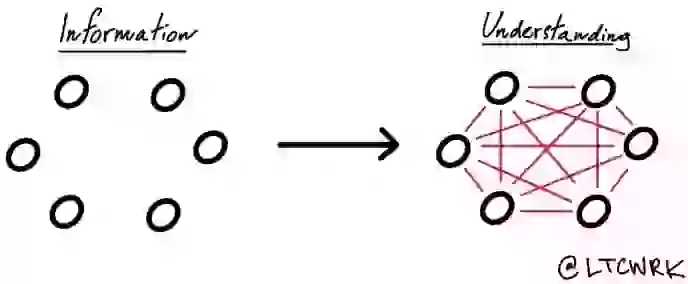

- When addiction is regarded as a relationship that develops through “repeated interaction” between a subject and an object, rather than a property that belongs solely to one or the other, it becomes clear that objects matter as much as subjects.

- While all forms of gambling involve random patterning of payouts, machine gambling is distinguished by its solitary, continuous, and rapid mode of wagering. Without waiting for “horses to run, a dealer to shuffle or deal, or a roulette wheel to stop spinning,” it is possible to complete a game every three to four seconds. To use the terminology of behavioral psychology, the activity involves the most intensive “event frequency” of any existing gambling activity. “It is the addiction delivery device,”

- Drawing on his intimate familiarity with the zone of machine gambling, Friedman goes on to describe the play that gamblers seek as an “inward focus into their own private domain [that] makes them oblivious to everything around them.” He insists that “the designer, marketer, and operator who best caters to this personal, introspective experience will attract and hold the most business.”

- From ceiling height to carpet pattern, lighting intensity to aisle width, acoustics to temperature regulation—all such elements, Freidman argues, should be engineered to facilitate the interior state of the machine zone.

- The chief task of casino design, according to Friedman, is to arrange “the spatial relationships of surrounding areas, the shape and feel of the structural box that encloses the setting” in such a way as to encourage machine gamblers’ entry into “secluded, private playing worlds.”

- Play itself Friedman describes as “open,” “undifferentiated,” “boundless,” “extensive,” and “never-ending”—precisely the phenomenological characteristics he strives to minimize within the gambling environment.

- The key is to cultivate “structured chaos” rather than “inhospitable commotion.” “The maze,” Friedman promises, “is the antidote.”

- Corridors draw people in not only by way of cues but also by way of curves. Casino patrons “resist perpendicular turning,” Friedman notes, for “commitment is required to slow down and turn 90 degrees into a slot aisle.”44 As a fellow industry member recalls, the reduction of “sharp lines” and the introduction of “very frequent curvature lines” became a strategic part of the casino’s design repertoire in the mid-1980s.45 “The role of the uninterrupted, curvilinear pathway couldn’t be more important,” commented an architect during a panel at the 2009 Global Gaming Expo.

- The job of casino layout is to suspend walking patrons in a suggestible, affectively permeable state that renders them susceptible to environmental triggers, which are then supplied.

- Calling to mind a Deleuzian conception of affect as dynamic states of sensing, energy, and attention outside of conscious awareness yet critical to action, atmospherics are understood to be most effective when they operate at a level that is not consciously detectible.

- Another acoustic element that must be carefully regulated to encourage play is music. A company called Digigram provides background music that can be scheduled by time of day, depending on the shifting demographics of a property’s clientele.

- The task of expediting “continuous gaming productivity,” as Cummings breaks it down, involves three interlinked operations, each of which this chapter will examine in turn: accelerating play, extending its duration, and increasing the total amount spent.

- Speed is a critical element of the zone experience. “I play really fast,” a middle-aged tax accountant named Shelly told me. “I don’t like to wait, I want to know what’s gonna come out. If a machine is slow, I move to a faster one.”

- “It was more about keeping the pace than making the right decisions.” “Keeping the pace” is critical to the zone experience, as gamblers articulate. “The speed is relaxing,” said Lola, a buffet waitress and mother of four. “It’s not exactly excitement; it’s calm, like a tranquilizer. It gets me into the zone.”

- “The play should take no longer than three and a half seconds per game.”

- Dematerializing money into an immediately available credit form not only disguised its actual cash value and thus encouraged wagering, it also mitigated the revenue-compromising limitations of human motor capacities by removing unwieldy coins from the gambling exchange.

- much as repeat machine gamblers want speed, they want to play for as long as possible. Their desire for “time-on-device,” as the gambling industry terms it, moves in tandem with the industry’s desire for continuous productivity. “The key is duration of play,” a consultant told me. “I want to keep you there as long as humanly possible—that’s the whole trick, that’s what makes you lose.” “It’s basically a matter of getting them into the seat and keeping them there,” echoed a machine designer. “I’m trying to make the customer feel comfortable. Feel in that cocoon.”

- Sound, when properly configured, “can actually energize the player, keep him there longer,”

- Incredible Technologies’ ContinuPlay—“sound technology that rewards steady play.”

- The Capacitive Touchscreen System (as Immersion’s system has been renamed) affirms play gestures as a way to “capacitate” continued gambling.

- When it comes to the state of suspended animation that gamblers call the zone and the industry calls continuous gaming productivity, an uninterrupted flow of play funds is as important as the speed and duration of the play activity itself.

- Purposive obfuscation, his comment suggests, is key to the seductive appeal of gambling machines.

- “Henry Ford of slots,” increased the number of symbols or “stops” on each reel from ten to twenty, thereby decreasing players’ odds of winning a jackpot and allowing machines to offer larger prizes and still remain profitable.19 He also expanded the viewing window on the reels so that players could see rows of symbols above and below the payline, increasing the likelihood that they would experience a “near miss”—the sensation of nearly having won produced by the sight of winning symbols adjacent to the payline.

- The degree of fascination that a given machine holds for its users, she argues, is directly related to the degree of unpredictability and aliveness that it conveys.

- Behavioral-psychological explanations for why near misses are so compelling include the “frustration theory of persistence,” in which near misses “have an invigorating or potentiating effect on any behavior that immediately follows it,” and the related theory of “cognitive regret,” in which players circumvent regret at having almost won by immediately playing again. “Almost hitting the jackpot,” noted the behaviorist psychologist B.

- As it happens, in 1953 Skinner had pointed in the other direction, using the slot machine to exemplify the most potent of reinforcement schedules—in which subjects never know when they will be rewarded, or how much.

- “People were playing that bank of machines around the clock, standing in line,” a designer recalled. What drew players was precisely what most in the industry believed would keep them away: the introduction of skill to machine play—“an entirely new performance attribute,” as an industry historian has written.

- Although the elements of choice making and skill might seem at odds with the dissociative flow of the zone, in fact they heighten players’ absorption by turning the passive expectancy of the traditional slot experience into a compelling, interactive involvement.

- players valued time-on-device and saw a way to glean their own sort of value from it. “If you were to take $100 and play slots, you’d get about an hour of play, but video-poker was designed to give you two hours of play for that same $100,”

- much money as three-reel slots per unit of time, they brought in twice as much revenue because gamblers played at them four times as long.

- Increasing games’ hit frequency increased the rate at which play was reinforced, and players’ changed expectations were then accounted for in subsequent design innovations, further ratcheting up the rate of reinforcement.

- With the introduction and development of a game whose mode of reinforcement—and thus profit—relied on minor but continuous rewards rather than on significant but sporadic rewards, a new gambler profile was taking center stage in the experience of gambling addiction. This profile embodied, in extreme form, the broader market’s gravitation from action to escape play, volatility to time-on-device—a trend that would grow in the next decade.

- Multiline video slots’ subtle yet radical innovation is precisely their capacity to make losses appear to gamblers as wins, such that players experience the reinforcement of winning even as they steadily lose. “Positive reinforcement hides loss,” a designer at Silicon Gaming explained to me. Compounding this reinforcement are the ambient and sensory cues that accompany “winning,” such as lights, music, and visual graphics.

- To illustrate the process, Katrina relates how one common feature of video slots, called “bonus rounds” or “free spins,” has affected her play. This type of feature randomly presents gamblers with an animated bonus game offering them a prize, a chance at a prize, or free spins on the machine—all of which grant more time-on-device.91 The “game-within-a-game” works in dynamic concert with the payout schedule of the base game, serving as a second layer of reinforcement.

- The casino floor is like our own extended focus group. We sit and play, participate, ask players what they think about our machines, and about other machines. The whole team does this—it’s as important for the sound engineers to know the customer as anyone else; even the math guy spends some hours observing, asking questions. You have to experience it to understand what people really want.

- Evoking the scene that Lola recounted at the start of this chapter, Adams told me of his own style in the field. “I go out there and sit down at a machine. I turn to the person next to me and say I design these things, that’s why I’ve been sitting here playing this machine next to you for twenty minutes, because this is what I do. Let me show you the storyboard for a new game—I want to know what you think. They’ll tell you everything.” In 1999, a veteran game designer spoke of such tactics with a mixture of pride and defensiveness. “The guys in the trenches—out there in casinos, on the floor—can run circles around the MBA guys who are starting to come in. The MBAs have been cubby-holed by their business training. I kick the hell out of ’em, and I don’t do it with metrics or pie charts.” Adams echoed this cowboy bravado: Other sorts of corporations come in and look at us guys with straws in our teeth and think they can take over, but the truth is, they can’t run this business using the typical MBA-type philosophy of business administration. A compartmentalized design process with focus groups and committees for each game feature, endless meetings over every color and sound, take a very, very long time to get the product to the field—it’s just too bureaucratic.

- patron worth, recommending that casinos give each customer a “recency score” (how recently he has visited), a “frequency score” (how often he visits), and a “monetary score” (how much he spends), and then create a personalized marketing algorithm out of these variables.40 “We want to maximize every relationship,” Harrah’s Richard Mirman told a journalist.41 Harrah’s statistical models for determining player value, similar to those used for predicting stocks’ future worth, are the most advanced in the industry.

- Inviting the player to voluntarily configure his own game and thereby giving him “complete control” would neutralize his fear of being controlled, Elsasser suggested. Instead of risking that the “rat people” become aware of the box, this logic goes, let the rats design their own Skinner box. Sylvie Linard, chief operating officer of Cyberview, reiterated the strategy: “Players are very intelligent, so why not be open and transparent and let them play with the [casino] operators, and add to the game with us? Some like free spins, some like interactive bonus rounds—so why not put players into the equation and ask them to build their own games, on demand?

- asked directly, developers invariably claim that players want “entertainment” or “fun,” defining this as stimulating engagement that derives from risk, choice, and a sense of participation. “Entertainment is the common denominator,” Randy Adams told me. “People want entertainment.” Gardner Grout confidently stated the same at the start of his interview: “Entertainment is what people want.” Yet toward the end of our exchange he said precisely the opposite. “What we didn’t get at the beginning is that people don’t really want to be entertained. Our best customers are not interested in entertainment—they want to be totally absorbed, they want to get into a rhythm.”

- People like to get into that particular zone.” “Gambling is not a movie,” echoed a casino operator in the course of a G2E panel, “it’s about continuing to play.”

- Gamblers most readily enter the zone at the point where their own actions become indistinguishable from the functioning of the machine. They explain this point as a kind of coincidence between their intentions and the machine’s responses.

- Noting a trend toward the design of games with “interactional and auditory special effects [that] serve to give the experience of being able to control and manipulate the production of the effect,” she observes that although such effects would seem to invite active rather than passive participation, in fact they tend to bring about states of absorptive automaticity rather than reflective decision making, blurring boundaries between players and the game. They do this, Ito argues, by way of their “unique responsiveness,” which “amplifies and embellishes the actions of the user in so compelling a way that it disconnects him from others and obliterates a sense of difference from the machine.” As Sherry Turkle writes in her landmark study of early video games, “the experience of a game that makes an instantaneous and exact response to your touch, or of a computer that is itself always consistent in its response, can take over.”

- Immediacy, exactness, consistency of response: the near perfect matching of player stimulus and game response in machine gambling might be understood as an instance of “perfect contingency,” a concept developed in the literature on child development to describe a situation of complete alignment between a given action and the external response to that action, in which distinctions between the two collapse.

- The tuning out of worldly choices, contingencies, and consequences in the zone of machine gambling depends on the exclusion of other people. “I don’t want to have a human interface” says Julie, a psychology student at the University of Nevada. “I can’t stand to have anybody within my zone.” Machine gamblers go to great lengths to ensure their isolation.

- At the same time that machine gambling alters the nature of exchange to a point where it becomes disconnected from relationships, it alters the nature of money’s role in the social world. Money typically serves to facilitate exchanges with others and establish a social identity, yet in the asocial, insulated encounter with the gambling machine money becomes a currency of disconnection from others and even oneself. Contrary to Clifford Geertz’s interpretation of gambling as a publicly staged conversion of money value into social status and worldly meaning, the solitary transaction of machine gambling converts money into a means for suspending collective forms of value.21 Although money’s conventional value is important initially as a means of entry into play, “once in a game, it becomes instantly devalued,” observes the gambling scholar Gerda Reith.22 “You put a twenty dollar bill in the machine and it’s no longer a twenty dollar bill, it has no value in that sense,” Julie tells me of bill acceptors in the mid-1990s.

- “It’s strange,” says Lola, “but winning can disappoint me, especially if I win right away.”23 As we have already seen, winning too much, too soon, or too often can interrupt the tempo of play and disturb the harmonious regularity of the zone.

- It’s not about winning, it’s about continuing to play.”

- The value of money reasserts itself precisely because money in its conventional, real-world state remains the underlying means of access to the zone.

- Modifications to reduce speed of play would slow the rate at which video reels “spin,” pause reels between spins, and increase the time interval between a bet and its outcome. Modifications to reduce duration of play would mandate time-outs at certain intervals, display a permanent onscreen digital clock, and present periodic pop-up reminders alerting players to the time and money they have spent (stricter time-based measures would require a mandatory cash-out at 145 minutes of continuous play, following a five- or ten-minute warning). To reduce magnitude of wagering, modifications would decrease maximum bet size per spin, remove bill acceptors (or restrict them to small bills), show bet amounts in actual cash value rather than as play credits, and dispense all wins in the form of cash, check, or electronic bank transfer rather than tokens or tickets that might be easily regambled; multiline, multicoin games would be required to decrease the number of betting lines and to remove the “bet maximum coins” feature.55 Another set of modifications would address machines’ mathematical sleights of hand by eliminating near-miss effects, restricting losses disguised as wins, phasing out virtual reel mapping on nonvideo reel slots, and requiring video slots to “balance their reels” so that all contain the same symbols, in accordance with player intuition.

What I got out of it.

- Schüll’s deep dive on the gambling industry and how it gets people to keep playing (low stakes games, removing friction, near wins, etc.) was fascinating to learn about. The negative side of infinite games (playing for the sake of playing) didn’t occur to me before this book and is a helpful nuance to consider.