-

Instead of taking a cushy job, Malone chose hardship and a pay cut to join TCI, an obscure company that had lurched from crisis to crisis for the preceding 20 years. Bob Magness, a former cottonseed salesman and cattle rancher used a wobbly foundation of brinkmanship, bald faced gambles, and abundant debt to build TCI into the fourth largest cable provider in the US. Malone had picked TCI because Magness, fatigued and running out of luck, was ready to relinquish power and let a new man run the entire show - and because, if Malone could make it work, he might become extremely wealthy. TCI, which had become a publicly owned company in 1970, might be a diamond in the rough. “I can’t pay you very much, but you’ve got a great future here if you can create it,” Magness told Malone. Malone was more of a treasurer than the president his first few years at TCI – fending off lenders, raising money, talking to analysts, and more.

-

Malone started at TCI and helped make it a powerhouse through acquisitions and financial engineering. The structures of the deals were exotic, and his financial alchemy often befuddled Wall St. and investors. The flurry of complex mergers, acquisitions, stock dividends and spin-offs clouded the picture of the company's true performance, which was phenomenal by one measure that counts in almost all business: shareholder value. A single share of TCI, purchased at the 1974 low of 75 cents was worth $4,184 by the end of 1997 - a 5578 fold increase. His shareholders got very rich alongside Malone. For Malone, it was a noble, if not moral achievement, the fruit of his enormous capacity to deduce and strategize

-

Magness was a master at reading people – he got Malone on board by playing to his desire for control over his future and freedom to lead. His wife was also an astute business partner, cotton raiser and learned to listen rather than talk – reading what a person wanted in every negotiation

-

Learned of cable antenna TV (CATV) and started it in Memphis, Texas. If pulled off, he would be able to charge his neighbors a monthly fee for the television service – which he would get free of charge, basically pirating the programming from the TV stations themselves without paying a cent. He directed the construction, climbing the poles himself to string wire, while Betsy deciphered the finances and took service calls at the kitchen table. He invested everything he had, and still he had to go into debt. He sold this operation a few years later at a handsome profit. Tax laws made it attractive to reinvest as cable operators could gradually write off the cost of their systems over a number of years, allowing them to reduce the leftover profits they reported as earnings and thereby sheltering a healthy cash flow from taxation. And once they had written off most of the value of a cable system’s assets, they could sell it to a new owner, who could begin the tax-eluding depreciation cycle all over again.

-

Don’t need to be a genius if you can see and place yourself ahead of a wave

-

Magness never wrote a memo but the headquarters in Bozeman were Spartan and this frugality never left Magness or Malone. By the mid-1960s, Bob Magness had realized the potential of community antenna to fill a vast need; he likened cable to the oil rush days in his native Oklahoma and Texas. It was genius, really, to anyone who took the time to figure it out. Cable TV systems generated bundles of cash from installation charges and monthly service fees. Most of the money was plowed back into the companies, with hardly anything going to pay dividends to shareholders. This high cash flow could service an immense amount of debt, which was used to buy more systems. The companies paid hardly any taxes because of the high depreciation on the equipment – the average cable system enjoyed a profit margin of 57%, far better than most businesses. Because of this structure, and the tax incentives, TCI had to keep expanding, no matter what, buying up new cable companies to start the write-off process anew and build cash flows. To fund TCI’s expansion, Malone courted companies with capital to invest and an abiding interest in cable – but no expertise. Malone used different classes of shares with differing voting rights. A standing joke around TCI was that if TCI ever did report a large profit, Malone would fire the accountants. Malone had to “teach” the street what was really important – there is a big difference between creating wealth and reporting income. A focus on cash flow rather than reported income was hard for most to accept and was controversial for decades but those who invested alongside Malone would come to benefit greatly. He always pushed a long-term mindset and time horizon.

-

The next step from owning cable that delivered the programming, was to own a piece of the cable channels themselves, thereby sharing in a whole extra upside. This way, TCI could own both the pipe and the water flowing through it. Vertical integrating of companies would become an awesomely powerful and controversial tool in building TCI. TCI came to own parts of BET, MTV, the Discovery Channel, and many more

-

Malone was able to be patient when things got too expensive, building up cash reserves, making smaller acquisitions, and waiting for prices to normalize after the buying frenzy dried up.

-

Malone’s father was gone a lot, had very high expectations for John and John wanted to prove himself and gain his acceptance. He did this in school (especially math), through track and field, and other entrepreneurial adventures. His father always recommended “guessing at the answers” before he saw them. Guess before you figure them out helped him develop an intuition and make split second decisions and was an important weapon of his – allowing him to “see” the answers before others did.

-

Malone worked for Bell Labs out of school and focused on economic modeling and proposed that AT&T to shift its debt-to-equity ratio, taking on more debt and buying back its own stock in the market

-

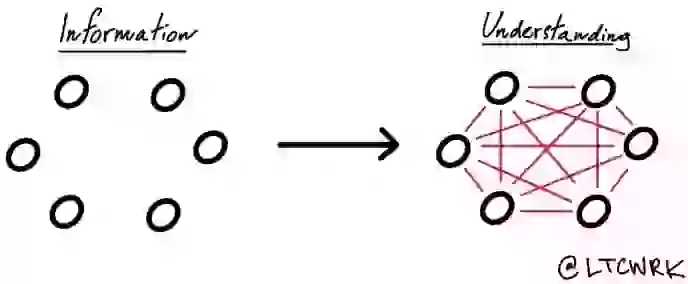

When Malone moved to McKinsey, he started by interviewing everyone from the senior ranks to the new hires. What works? What doesn’t? How would you fix it? Over time, Malone found that if he interviewed 30 people or so and listened intently, themes would emerge. The best ideas were sometimes hidden, or they were lost on senior executives. By laying the patterns bare, studying in detail the disparate parts – not unlike disassembling a radio – he learned how big corporations don’t work. It was not rocket science, Malone realized, you simply take the best ideas from anyone who has them, polish tem, and serve them up to the chairperson. His mind was like a spread of glue – it held fast any concept or pattern it encountered.

-

Main rule he learned at McKinsey: listen intently

-

Always ask the question, “if not..?”

-

Loyalty is more important than anything else

-

Malone’s strategy was simple: get bigger

-

Malone, like Magness, didn’t believe in memos. No paper passed from his desk to his underlings. No executive sought to curry favor or engage in the sort of Kremlinesque politics that caused ulcers in so many midlevel executives. Communication was direct, effective, and efficient. Every Monday morning, Malone sat with his closest executives at a broad round table, to figure out a way to squeeze more out of TCIs growing cable kingdom.

-

The TCI men were cable cowboys. Though the term was repeated in derision by the bankers and politicians who coined it, the TCI team wore the nickname like a badge

-

Malone liked to use naval metaphors, such as bulkheads, to describe the setup. Large ships are designed to withstand battle damage because they have watertight bulkheads, separate and self-contained compartments that can be sealed off to prevent an injured vessel from capsizing. You can take a torpedo in any one part and still stay afloat. With each new system he bought the debt was secured by a TCI subsidiary, not by the parent company. So, if the cable system defaulted on a loan, only one subsidiary would be threatened. Another way Malone eased risk was to spread it out among an ever-broadening array of partners, thereby protecting TCI and enhancing its influence in the industry at the same time. Aside from the cable systems that were wholly owned by TCI, the company was a minority partners in more than 35 cable companies, all of which got the same price breaks in programming that TCI got – which amounted to as much as a 30% discount.

-

Importance of courage

-

In the early days, TCI was struggling financially and Malone met with the main lenders to ask them to bring down the interest rates because of the healthy cash flows. They countered instead by proposing to raise the rates and Malone told them they could have the keys and raise the interest rates if they thought they could run the company better than he. They backed down and gave TCI some room to breathe

-

Malone avoided acquiring at sky high prices during bubbles but once it burst, scooped in with a vengeance. Malone relished the role of bargain hunter amid the spoils of bad deals made by his competitors. Was able to wait without tiring of waiting

-

Later on, Malone and Magness cut several deals that allowed executives to own cable systems privately, then eventually turn them over to TCI. For Malone, it was a way not only of compensating his top employees as the values grew but, more importantly, to teach them. “Guys will understand a cable system a hell of a lot better if they have skin in the game.” Critics may have judged the deal as enriching insiders, but Malone paid little attention. Malone’s attitude was: you don’t like the way we reward management? Don’t buy the stock

-

By 1986, TCI was beginning to run the way Malone had wanted it to run – highly decentralized. He had cut the company into 6 separate operating divisions, each nearly autonomous, with its own accounting and engineering departments. When you’ve got it running right, when you’ve got it decentralized, when you’ve got it structured properly, it’s like flying the most powerful fighter jet in the world

-

One of the hallmarks of Malone’s management style was to leave the founder in charge. If you buy a property and find a manager motivated by ownership in the company, keep him or her in power and trust him or her implicitly

-

Forget about earnings: what you really want is appreciating assets. You want to own as much of that asset as you can; then you want to finance it as efficiently as possible. And above all else, make sure that the deals you do avoid as much in taxes as legally possible. And then some.

-

Never sacrifice convictions at whims of others, no matter what the price

-

Instead of high salaries, paid in equity which helped align incentives

-

The idea, Malone liked to think, was to collaborate with your enemies – especially your enemies – to avoid the large and costly fight of real competition. It’s like mutually assured destruction: both sides could really hurt the other if they did something really stupid. We have to treat each other with civility to avoid all-out nuclear war.

-

Redstone’s motto: content is king

-

Tough times in the industry created incredibly tight bonds among the people at TCI

-

Cable franchise essentially a legal right to a local monopoly

-

The Cable Communications Act of 1984, the first national legislation establishing government authority over cable TV, ushered in a new era of growth, opening up financial markets, programming ideas, and billions of dollars in untapped revenue to cable. The law also kept the giant phone companies at bay, forbidding them from owning cable systems in their service areas. Incredible bidding wars ensued between cable operators and telcos. While cable had a fatter pipe, phone companies could offer cable firms badly needed capital and world-class expertise in switched, two-way communications. The first big move by a Bell came just two weeks after Malone made his 500-channel pledge. Both cable and telcos wanted to deploy similar technology but over separate sets of wires: cable companies over their thick coaxial cable lines and telcos over their twisted-pair copper networks. Coaxial cables offered orders of magnitude more data to be sent than the high speed lines of phone companies.

-

“Malone is the kind of guy you want to run through walls for”

-

“I’d gladly give my life to save his” – Ted Turner

-

Used scale, penetration to get discounts and ownership of channels. The more horses Malone bet on, the likelier his chances of winning – BET, MTV, QVC, CVN. By 1988, TCI generated $850m in cash. Though it had no earnings, it had more cash flow than ABC, CBS, and NBC combined.

-

Malone’s incredible commitment and focus had a massive strain on his family life. He also made enemies because he was seen as a bully, as taking a disproportionate share of the wealth he created, was unrepentant and unabashed about his and TCI’s clout

-

Set up Liberty to prevent regulation, anti-trust, but also to make him very rich as he had 20% ownership. Used tracking stocks often – an interest in the earnings of the company but don’t own the underlying assets.

-

After the 1992 regulation, Malone came up with the “500 channel” vision and interactive TV

-

Maine and his boat were Malone’s retreat. Escape is necessary. Getting away gives you a new perspective and makes you more human. When you’re running a large corporation, you’re not able to show your human side all that much. It’s just not productive.

-

Don’t chase too many rabbits simultaneously – know your main goals and focus on them intently until you reach them or find a more important goal to focus on

-

Malone believes his greatest weakness was allowing his loyalty to get ahead of performance.

-

One of the TCI insider’s favorite analogies for TCI’s problems was that TCI was a gas station company acting like a pipeline company. Pipelines deliver fuel in bulk. But gas stations sell it to retail customers, a far more service-oriented business. Customer service would win the day, and no one could argue that TCI didn’t need to pay more attention to its customers. Running a pipeline business is a pretty easy business – you just turn on a pump. Running gas stations is a really hard business. Hindrey wanted to put marketing and purchasing decisions back in the hands of local operators. You market from the bottom up, and not from the top down. What works in Bozeman doesn’t work in Birmingham. He also demanded to see copies of customer complaints for weeks at a time

-

In June 1997, Bill Gates became cable’s savior in one simple, decisive move: he had shocked Wall St. by having Microsoft invest $1b in cash in Comcast at the behest of Brian Roberts. Until then, cable had been left for dead; the reregulation effort had crimped cash flow, the industry faced huge investment to go fully interactive, and cable stocks were near all-time lows. Suddenly everyone wanted to know the answer to the question: just what does Bill Gates know that we don’t? Gates had bought on the cheap and though he would be involved in the coming years, Malone and others were careful not to let Microsoft get too ingrained by having their software become the default on cable top boxes.

-

Malone had a “3-D chess” type of mind – truly has the hologram in the head

-

If you can get scale economics, you can get the costs down. If you get the costs down, you get the scale economics. It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. If you get the scale economics you can develop applications that are really important to a lot of people. If you can get applications that are important to people, you get people to buy the boxes, and you’ll get more scale economics

-

Malone almost always reached out directly to deal. He would pick up the phone and reach out to the other side and look for the common ground where he could put together a mutually agreeable deal – win/win

-

Malone Family Foundation – to promote the secondary and liberal arts education of the most able young men and women of our society and train such individuals as future leaders of society; acquire and preserve land and open space, preserving forever Nature’s natural and pristine beauty

-

Malone was a man who was fiercely proud of what he had accomplished. A man who believed that wealth creation was a noble, moral achievement and believed the definition was not freedom from obligation, but freedom to choose which of those obligations to take on, which roles to play in business and in life.

-

TCI made wealth not by pretending to be the best cable operator but through investments and complex financial engineering.

-

Once TCI was sold to AT&T, Malone wanted to create separate stocks for the stable, dividend paying business and the more growth-oriented businesses. He wanted, as Jack Welch had done at GE, to create autonomous units with a total delegation of operational parameters within budgeting controls. If you do these things, you’ll have a great company and you will maximize shareholder value. Malone had pulled off one of the largest sales in the history of telecommunications and the IRS had to treat it as a tax-free stock merger. Basically, Malone had exchanged his personal stake of $1.7b in TCI and Liberty for $2.4b in AT&T and Liberty stock. Malone always paid as little in taxes and as late as possible. It is my job to save as much of shareholder’s money as I can

-

Later, Malone got into raising cattle. He loved the inherent efficiencies in hybrid vigor, the known improvements in growth or yield in one generation of hybrids over their parents. The idea is to have a 1,000 pound cow producing a 550 pound calf at weaning. She is more efficient. The smaller the cow, the less grass she eats. If you get a 2,000 pound cow producing a 300 pound weaning calf, you are doing it the wrong way. He also bought a ton of land and the basic idea was to own land in pretty places that haven’t been ruined yet and to not develop it. The elements of success in cable could also be applied to buying land: scale, timing, and efficiency. Almost all of the land and ranch purchases by Malone had a single element in common: conservation easements, which allow landowners to take charitable tax deductions if they opt to never develop a property.