- The Mediocrity Principle

- The mediocrity principle simply states that you aren’t special. The universe does not revolve around you; this planet isn’t privileged in any unique way; your country is not the product of divine destiny; your existence isn’t the product of directed, intentional fate. Most of what happens is just a consequence of natural, universal laws – laws that apply everywhere and to everything, with no special exemptions or amplifications for your benefit…We look for general principles that apply to the universe as a whole first, and those explain much of the story; and then we look for the quirks and exceptions that led to the details. It’s a strategy that succeeds and is useful in gaining a deeper knowledge.

- Double-Blind Control Experiment (Richard Dawkins)

- We would learn not to generalize from anecdotes

- We would learn how to assess the likelihood that apparently important effects might have happened by chance alone

- We would learn how extremely difficult it is to eliminate subjective bias, and that subjective bias does not imply dishonesty or venality of any kind. This lesson goes deeper. It has the salutary effect of undermining respect for authority and respect for personal opinion

- We would learn not to be seduced by homeopaths and other quacks and charlatans, who would consequently be put out of business

- We would learn critical and skeptical habits of thought more generally, which not only would improve our cognitive toolkit but might save the world

- Scientific Method

- The core of a scientific lifestyle is to change your mind when faced with information that disagrees with your views, avoiding intellectual inertia, reflecting the past rather than shaping the future.

- Thought Experiment

- It involves setting up an imagined piece of apparatus and running a simple experiment with it in your mind, for the purpose of proving or disproving a hypothesis. In many cases, a thought experiment is the only approach. An actual experiment to examine retrieval of information falling into a black hole cannot be carried out.

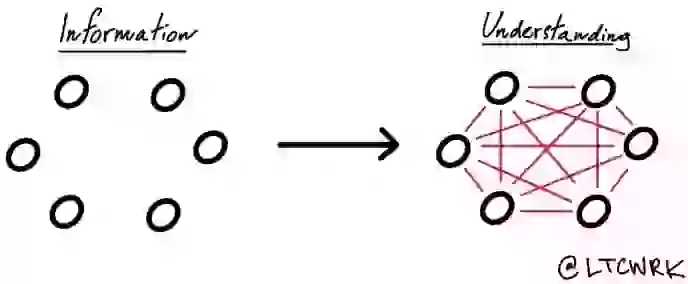

- Nexus Causality

- For many things, it is more accurate to represent outcomes as caused by an understanding, or nexus, of factors

- Self-Serving Bias

- Most of us have a good reputation with ourselves. Accepting more responsibility for success than for failure, for good deeds than for bad

- Bias is the nose for the story

- Bias, in the form of expectation, inclination, and anticipatory hunches, helped load the dice in our favor and for that reason is hardwired into our thinking. Bias is an intuition – a sensitivity, a receptiveness – that acts as a lens on all our perceptions

- Control your spotlight

- Willpower is inherently weak and children who tried to postpone their treat – gritting their teeth in the face of temptation – soon lost the battle, often within thirty seconds. Instead, Mischel discovered something interesting when he studied the tiny percentage of kids who could successfully wait for the second treat. Without exception, these “high delayers” all relied on the same mental strategy: they found a way to keep themselves from thinking about the treat, directing their gaze away from the yummy marshmallows. This is the skill of “strategic allocation of attention,” and Mischel argues that it’s the skill underlying self-control. Too often, we assume that willpower is about having strong moral fiber. But that’s wrong. Willpower is really about properly directing the spotlight of attention, learning how to control that short list of thoughts in working memory. It’s about realizing that if we’re thinking about the marshmallow, we’re going to eat it, which is why we need to look away.

- The focusing illusion

- Income is an important determinant in people’s satisfaction with their lives, but it is less important than most people think. If everyone had the same income, the differences among people in life satisfaction could be less than 5%

- Uncertainty

- Uncertainty is a central component of what makes science successful. Being able to quantify uncertainty and incorporate it into models is what makes science quantitative rather than qualitative. Indeed, no number, no measurement, no observable in science is exact. Quoting numbers without attaching an uncertainty to them implies that they have, in essence, no meaning

- Because

- When you’re facing in the wrong direction, progress means walking backward. History suggests that our worldview undergoes disruptive change not so much when science adds new concepts to our cognitive toolkit as when it takes away old ones.

- The name game

- Too often in science we operate under the principle that “to name it is to tame it,” or so we think. One of the easiest mistakes, even among working scientists is to believe that labeling something has somehow or other added to an explanation or an understanding of it. The normal fallacy is the error of believing that the label carries explanatory information. Stuart Firestein

- Living is fatal

- Probabilities are numbers whose values reflect how likely different events are to take place. People are bad at assessing probabilities. They are bad at it not just because they are bad at addition and multiplication. Rather, people are bad at probability on a deep, intuitive level: they overestimate the probability of rare but shocking events – a burglary breaking into your bedroom while you’re asleep, say, Conversely, they underestimate the probability of common but quiet and insidious events – the slow accretion of globules of fat on the walls of an artery, or another ton of carbon dioxide pumped into the atmosphere.

- This blind spot in our collective consciousness – the inability to deal with probability – may seem insignificant, but it has dire practical consequences. We are afraid of the wrong things, and we are making bad decisions.

- Truth is a model

- Bugs are features – violations of expectations are opportunities to refine them. And decisions are made by evaluating what works better, not by invoking received wisdom.

- abies who keep babbling turn into scientists who formulate and test theories for a living. But it doesn’t require professional training to make mental models – we’re born with those skills. What’s needed is not displacing them with certainty of absolute truths that inhibit the exploration of ideas. Making sense of anything means making models that can predict outcomes and accommodate observations. Truth is a model

- Failure liberates success

- Often the only way to improve a complex system is to probe its limits by forcing it to fail in various ways

- Holism

- The whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Perhaps the most impressive is that carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur, phosphorous, iron, and a few other elements, mixed in just the right way, yield life. And life has emergent properties not presenting or predictable from these constituent parts. There is a kind of awesome synergy between the parts. Nicholas Christakis

- TANSTAAFL

- There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch

- The universality of the fact ta you can’t get something for nothing has found application in sciences as diverse s physics (laws of thermodynamics) and economics.

- Shifting baseline syndrome

- Each generation of fisheries scientists accepts as a baseline the stock and size and species composition that occurred at the beginning of their careers and uses this to evaluate changes. When the next generation starts its career, the stocks have further declined, but it is the stocks at the time that serve as a new baseline. The result is obviously a shift in the baseline, a gradual accommodation of the creeping disappearance of resources species

- A shift, for the better or worse

- Positive-Sum Games

- A zero-sum game is an interaction in which one party’s gain equals the other party’s loss – the sum of their gains and losses is zero. Sports matches are quintessential examples of zero-sum games: winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing, and nice guys finish last. A nonzero-sum game is an interaction in which some combinations of actions provide a net gain (positive sum) or loss (negative sum) to the two participants. The trading of surpluses, as when herders and farmers exchange wool and milk for grain and fruit, is a quintessential example, as is the trading of favors, as when people take turns baby-sitting each other’s children. In a zero-sum game, a rational actor seeking the greatest gain for himself or herself will necessarily be seeking the maximum loss for the other actor. In a positive-sum game, a rational self-interested actor may benefit the other actor with the same choice that benefits himself or herself. More colloquially, positive-sum games are called win-win situations and are captured in the cliché “everybody wins.”

- Structured Serendipity

- Two techniques seem very promising: varying what you learn and varying where you learn it. I try each week to read a scientific paper in a field new to me – and to read it in a different place. New associations often leap out of the air at me this way…In my view, we should each invest a few hours a week in reading research that ostensibly has nothing to do with our day jobs, in a setting that has nothing in common with our regular workspaces

- Randomness

- Randomness is so difficult to grasp because it works against our pattern-finding instincts. It tells us that sometimes there is no pattern to be found. As a result, randomness is a fundamental limit to our intuition; it says that there are processes we can’t predict fully

- The First Law of Randomness: There is such a thing as randomness. Random events can mimic nonrandom ones

- The Second Law of Randomness: Some events are impossible to predict

- The Third Law of Randomness: Random events behave predictably in aggregate even if they’re not predictable individually. The larger the number of events, the more predictable they become. The law of larger numbers is a mathematical theorem that dictates that repeated, independent random events converge with pinpoint accuracy upon a predictable average behavior

- Cognitive Load

- The amount of information entering our consciousness at any instant is referred to as our cognitive load. When our cognitive load exceeds the capacity of our working memory, our intellectual abilities take a hit. Information zips into and out of our mind so quickly that we never gain a good mental grip on it. The information vanishes before we’ve had an opportunity to transfer it into our long-term memory and weave it into our knowledge.

- To curate

- “To curate” is finding ever wider application because of a feature of modern life impossible to ignore: the incredible proliferation of ideas, information, images, disciplinary knowledge, and material products we all witness today. Such proliferation makes the activities of filtering, enabling, synthesizing, framing, and remembering more and more important as basic navigational tools for 21st century life. These are the tasks of the curator, who is no longer understood simply as the person who fills a space with objects but also as the person who brings different cultural spheres into contact, invents new display features, and makes junctions that allow unexpected encounters and results. – Hans Ulrich Obrist, This Will Make You Smarter

- The senses and the multisensory

- What we call “Taste” is one of the most fascinating case studies for how inaccurate our view of our senses is: it is not produced by the tongue alone but is always an amalgam of taste, touch, and smell, touch contributes to sauces tasting creamy and other foods tasting chewy, crisp, or stale. Flavor perception is the result of multisensory integration of gustatory, olfactory, and oral somatosensory information into a single experience whose components we are unable to distinguish. In sensory perception, multisensory integration is the rule, not the exception

- Other surprising collaborations among the sense are due to cross-model effects, whereby stimulation of one sense boosts activity in another. Looking at someone lips across a crowded room can improve our ability to hear what they are saying, and the smell of vanilla can make a liquid we sip “taste”

- Think bottom up, not top down

- One of the most general shorthand abstractions that, if adopted, would improve the cognitive toolkit of humanity is to think bottom up, not top down. Almost everything important that happens in both nature and society happens from the bottom-up, not top down. Water is a bottom-up, self-organized emergent property of hydrogen and oxygen. Life is a bottom-up, self-organized emergent property of organic molecules that coalesced into protein chains through nothing more than the input of energy into the system of Earth’s early environment. The complex eukaryotic cells of which we are made are themselves the product of much simpler prokaryotic cells that merged together from the bottom up, in a process of symbiosis that happens naturally when genomes are merged between two organisms. Evolution itself is a bottom-up process or organisms just trying to make a living and get their genes into the next generation; out of that simple process emerges the diverse array of complex life we see today. Most people, however, see the world from the top down instead of the bottom up. The reason is that our brains evolved to find design in the world, and our experience with designed objects is that they have a designer (us), whom we consider to be intelligent. So, most people intuitively sense that anything in nature that looks designed must be so from the top down, not the bottom up. Bottom-up reasoning is counterintuitive. This is why so many people believe that life was designed and that countries should be ruled from the top down

- For the past 500 years, humanity has gradually but ineluctably transitioned from top-down to bottom-up systems, for the simple reason that both information and people want to be free

- Scaling Laws

- Scaling Laws are found throughout nature. Galileo in 1638 pointed out that large animals have disproportionately thicker leg bones than small animals to support the weight of the animal. The heavier animal, the stouter their legs need to be. This leads to a prediction that the thickness of the leg bone should scale with 3/2 power of the length of the bone

- Constraint satisfaction

- A constraint is a condition that must be taken into account when solving a problem or making a decision, and “constraint satisfaction” is the process of meeting the relevant constraints. The key idea is that often there are only a few ways to satisfy a full set of constraints simultaneously

- In general, the more constraints, the fewer the possible ways of satisfying them simultaneously. And this is especially the case when there are many “strong” constraints’ strong constraint is like the positioning of the end tables: there are very few ways to satisfy it. In constant, a “weak” constraint such as the location of the headboard, can be satisfied in many ways. Constraint satisfaction is pervasive in part because it does not “require” perfect solutions. It’s up to you to decide what the most important constraints are and just how many of the constraints in general must be satisfied (and how well). Moreover, constraint satisfaction need not be linear: you can appreciate the entire set of constraints at the same time, throwing them into your mental stewpot and letting them simmer. And this process need not be conscious. “Mulling it over” seems to consist of engaging in all-but-unconscious constraints satisfaction. Finally, much creativity emerges from constraint satisfaction. Many new recipes have been created when chefs discovered that only certain ingredients were available – and they thus were either forced to substitute those missing or come up with anew dish. Creativity can also emerge when you decide to change, exclude, or add a constraint. Einstein had one of his major breakthroughs when he realized that time need not pass at a constant rate. Perhaps paradoxically, adding constraints can actually enhance creativity – if a task is too open or unstructured, it may be so unconstrained that it’s difficult to devise any solution.

- Keystone consumers

- The term “keystone species,” inspired by the purple sea star, refers to a species that has a disproportionate effect relative to its abundance. Similarly, it is possible for a small minority of humans to precipitate the disappearance of an entire species

- Cumulative error

- Humor seems to be the brain’s way of motivating itself – through pleasure – to notice disparities and cleavages in its sense of the world. In the telephone game, we find glee in the violation of expectation; what we think should be fixed turns out to be fluid

- Scale analysis

- Nonlinearity is a hallmark of the real world. It occurs any time that outputs of a system cannot be expressed in terms of a sum of inputs, each multiplied by a simple constant – a rare occurrence in the grand scheme of things. Unpredictable variability, tipping points, sudden changes in behavior, hysteresis – all are frequent symptoms of a nonlinear world. One of the most robust bridges between the linear and the non-linear, the simple and the complex, is scale analysis, the dimensional analysis of physical systems. It is throughs scale analysis that we can often make sense of complex nonlinear phenomena in terms of simpler models. At its core reside two questions. The first asks what quantities matter most to the problem at hand (which tends to be less obvious than one would like). The second asks what the expected magnitude and – importantly – dimensions of such quantities are. This second question is particularly important, as it captures the simple yet fundamental point that physical behavior should be invariant to the units we use to measure quantities.

- Of course, anytime a complicated system is translated to a simpler one, information is lost. Scale analysis is a tool only as insightful as the person using it. By itself, it does not provide answers and is no substitute for deeper analysis. But it offers a powerful lens through which to view reality and to understand “the order of things”

- Science

- The idea that we can systematically understand certain aspects of the world and make predictions based on what we’ve learned, while appreciating and categorizing the extent and limitations of what we know, plays a big role in how we think

- The expanding in-group

- The phenomenon of hybrid vigor in offspring, which is also called heterozygote advantage, derives from a cross between dissimilar parents. It is well established experimentally, and the benefits of mingling disparate gene pools are seen not only in improved physical but also improved mental development. Intermarriage therefore promises cognitive benefits

- Life is a self-replicating hierarchy of levels

- The Pareto Principle

- Also known as the 80/20 rule, Zipf’s law, the power-law distribution, winner-take-all, but the basic shape of the underlying distribution is always the same: the richest or busiest or most connected participants in a system will account for much, much more wealth or activity than average. Furthermore, the pattern is recursive. Within the top 20 of a system that exhibits a Pareto distribution, the top 20% of that slice will also account for disproportionately more of whatever is being measured, and so on.

- The top 1% of the population controls 35% of the wealth

- The recursive 80/20 weighting means that the averages far from the middle. This in turn means that in such systems most people are below average, a pattern encapsulated in the old economics joke, “Bill Gates walks into a bar and makes everybody a millionaire, on average.”

- We are lost in thought

- We must recognize thoughts as thoughts, as transient appearances in consciousness – is a primary source of human suffering and confusion

- Information flow

- The concept of cause-and-effect is better understood as the flow of information between two connected events, from the earlier event to the later one. If you can master the technique of visualizing all information flow and keeping track of your priors, then the full power of the scientific method – and more – is yours to wild from your personal cognitive toolkit.

- Negative capability

- Being able to exist with lucidity and calm amid uncertainty, mystery, and doubt, without “irritable reaching after fact and reason”

- Systemic equilibrium

- The second law of thermodynamics states that, over time, a closed system will become more homogenous, eventually reaching systemic equilibrium. It is not a question of whether a system will reach equilibrium; it is only a question of when a system will reach equilibrium. Living on a single planet, we are all participants in a single physical system that has only one direction – toward systemic equilibrium. This goes for food, water, intellectual resources, and more

- Recursive structure

- Recursive structure is a simple idea with surprising applications beyond science. A structure is recursive if the shape of the whole recurs in the shape of the parts: for example, a circle formed f welded links that are circles themselves. Each circular link might itself be made of smaller circles, and in principle you could have an unbounded nest of circles made of circles made of circles. Some parts of nature show recursive structure of a sort: a typical coastline shows the same shape or pattern whether you look from six inches away or sixty feet or six miles

- The recurrence of this phenomenon in art and nature underlines an important aspect of the human sense of beauty.

- Collective intelligence

- Human achievement is entirely a networking phenomenon. It is by putting brains together through the division of labor – through trade and specialization – that human society stumbled upon a way to raise the living standards, carrying capacity, technological virtuosity, and knowledge base of the species. By sharing and combining the results through exchange, people become capable of doing things they do not even understand

- The base rate

- Whenever a statistician wants to predict the likelihood of some event based on the available evidence, there are two main sources of information that have to be taken into account: the evidence itself, for which a reliability figure has to be calculated; and the likelihood of the event calculated purely in terms of relative incidence. The second figure is the base rate

- Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence

- Path dependence

- The fact that often something that seems normal or inevitable today began with a choice that made sense at a particular time in the past but survived despite the eclipse of its justification, because, once it had been established, external factors discouraged going into reverse to try other alternatives. The paradigm example is the seemingly illogical arrangement of letters on typewriter keyboard. Why not just have the letters in alphabetical order, or arrange them so that the most frequently occurring ones are under the strongest fingers? In fact, the first typewriter tended to jam when typed on too quickly, so its inventor deliberately concocted an arrangement that put “A” under the ungainly little finger.

- Ecology

- We now increasingly view life as a profoundly complex web like system with information running in all directions, and instead of a single hierarchy we see an infinity of nested and codependent hierarchies – and the complexity of all this is, in and of itself, creative. We no longer need the idea of superior intelligence outside the system; the dense field of intersecting intelligences is fertile enough to account for all the incredible beauty of “creation.”

- The paradox

- Paradoxes arise when one or more convincing truths contradict each other, clash with other convincing truths, or violate unshakeable intuitions. They are frustrating, yet beguiling. Many see virtue in avoiding, glossing over, or dismissing them. Instead we should seek them out. If we find one, sharpen it, push it into the extreme, and hope that the resolution will reveal itself, for with that resolution will invariably come a dose of Truth.

- Nature appears to contradict itself with the utmost rarity, and so a paradox can be an opportunity for us to lay bare our cherished assumptions and discover which of them we must let go. But a good paradox can take us further, to reveal that not just the assumptions but the very modes of thinking we used in creating the paradox must be replaced. Particles and waves? Not truth, just convenient models. The same number of integers as perfect squares of integers? Not crazy, though you might be, if you invent cardinality. The list goes on.

- Swiss Cheese model

- Losses occur only if all controls fail and the holes in the Swiss cheese align

- Black swan technologies

- With a black swan technology shot, you need not be constrained by the limits of the current infrastructure, projections, or market. You simply change the assumptions

- Entanglement

- Entanglement is spooky action at a distance. In quantum physics, two particles are entangled when a change in one particle is immediately associated with a change in the other particle. Here comes the spooky part; we can separate our “entangled buddies” as far as we can, and they will remain entangled. A change in one is instantly reflected in the other, even though they are physical far apart!

- Time span of discretion

- Half a century ago, while advising a UK Metals company, Elliott Jaques had a deep and controversial insight. He noticed that workers at different levels of the company had very different time horizons. Line workers focused on tasks that could be completed in a single shift, whereas managers devoted their energies to tasks requiring six months or more to complete. Meanwhile, their CEO was pursuing goals realizable only over the span of several years

- He who thinks longest wins

- The Einstellung Effect

- We constantly experience it when trying to solve a problem by pursuing solutions that have worked for us in the past, instead of evaluating and addressing the new problem on its own terms. Thus, whereas we may eventually solve the problem, we may be wasting an opportunity to do so in a more rapid, effective, and resourceful manner.

- Phase and Scale Transitions

- Phase transition is a change of state in a physical system, such as liquid to gas. The concept has since been applied in a variety of academic circles to describe other types of transformation, from social (think hunter-gatherer to farmer) or statistical (think abrupt changes inn algorithm performance as parameters change) but has not yet emerged as part of the common lexicon. One interesting aspect of the phase transition is that it describes a shift to a state seemingly unrelated to the previous one and hence provides a model for phenomena that challenge our intuition. With knowledge of water only as a liquid, who would have imagined a conversion to gas with the application of heat?

- Scale transitions are unexpected outcomes resulting from increases in scale. For example, increases in the number of people interacting gin a system can produce unforeseen outcomes: the operation of markets at large scales is often counterintuitive. Think of the restrictive effect that rent-control laws can have on the supply of affordable rental housing, or how minimum-wage jobs can reduce the availability of low-wage jobs

- Statistically significant

- This means that the results are unlikely to be due by chance, the results themselves may or may not be important

What I got out of it

- An amazing compilation of important ideas which would make us all better thinkers if we studied and implemented them