- Good times breed laxity, laxity breeds unreliable numbers, and ultimately, unreliable numbers bring about bad times. This simple rhythm of markets is as predictable as human avarice.

- Investors are very good at recognizing the moods of the past—for example, the Roaring Twenties, the Great Depression, the Swinging Sixties—but we tend to be oblivious to the mood of the present. When do we notice that the world has changed? Sometimes change arrives with a bang. The dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima instantly and permanently changed the stakes of great-power conflicts. But more often, change creeps upon us incrementally, punctuated by upheavals that, often as not, are rationalized as part of business as usual.

- Those most adept at profiting from a particular market are often least likely to notice when the game is over, and probably the least psychologically prepared to profit from the successor market.

- But the market has even crueler twists. It’s not sufficient that a player figure out when the game has changed. When a market shifts, it usually requires the investor to adopt a psychological stance anathema to the precepts upon which he built his earlier success.

- The message is that mood or investor psychology is as important to markets as is information. It requires tremendous discipline to apply this understanding to one’s behavior.

- A good idea, a long-term perspective, and the creativity to implement a strategy to profit from your insight are necessary to prosper in finance, but they are not sufficient. None of these qualities will bear fruit unless you have the discipline to stay with your strategy when the market tests your confidence, as it inevitably will.

- This saga was more colorful than today’s studies of pricing anomalies in the derivatives market. Unencumbered by the received wisdom of a business education, I had to figure things out for myself. If you think things through for yourself, you may waste some time, but you also may stumble onto something that has been ignored or disregarded. Doing so has enabled me to look at the financial world with fresh eyes.

- I think that one of the greatest mistakes of economics was to separate itself from other disciplines. You can’t understand economics without understanding philosophy and history.

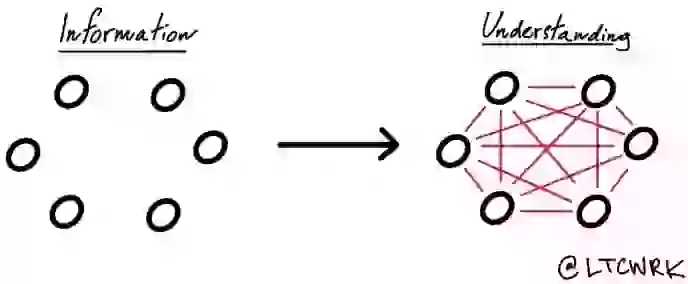

- If intelligence is the ability to integrate, creativity is the ability to integrate information from seemingly unconnected sources, and a measure of both abilities is necessary for long-term success in the markets.

- My passion for ancient history and archaeology also gives me perspective.

- All we can ever do is look at the past to predict the future, but life is dynamic and constantly changing, so the assumptions governing predictions are bound to be wrong.

- All specialists have a time frame that they believe is important—the astrophysicist who thinks in terms of billions of years can’t put himself in the mind of the meteorologist who thinks about the future in terms of hours and days. Both will be befuddled by the archaeologist whose time scale spans less that that of the astrophysicist but more than the meteorologist.

- Although Danny was clearly a master of the game, making money was not an end in itself for him. I think that is true of many successful people in finance. Apart from giving money away, they have passionate outside interests.

- mistake in launching the Oppenheimer Fund was in not sufficiently appreciating how skepticism about the unfamiliar can obscure the merits of even the best ideas.

- We hired Milton Pollack, a brilliant lawyer who later became a distinguished federal judge. The suit unfolded slowly, and I fell into a ritual of having dinner with Pollack once a month during which he would update me on our progress and his methods. At that time he had a daughter in elementary school; he told me that before he asked any question of a witness, he would test it on his daughter.

- Some of the best opportunities involve badly managed companies, if only because the situation can improve rapidly with the imposition of good management. No matter how bad a company, there is almost always a point where it is a bargain.

- the proper perspective on an investment is not what you have made so far, but rather the risk and reward ratio at any given point. The price you paid for a stock is irrelevant.

- I have thought about the myriad ways in which money flows toward tax incentives and away from high taxes and have concluded that taxes play a profound role in shaping history. Give officials control of the tax code and they can change society, either deliberately through the wise use of incentives or, more commonly, inadvertently through a misunderstanding of how people react to taxes. Until

- It is interesting to note that any profitable market strategy, no matter how obviously it is driven by greed, always is deemed good for society by those who reap the profits.

- Napoleon’s delusion was to believe in military strategy and underestimate the role of morale; his generals failed to appreciate that Russian citizens battling for their lives on their home soil had far greater incentive to fight than did a poilu from Paris yearning for the Champs Elysées. The LTCM strategists’ delusion was to watch a market go mad and fail to appreciate the degree to which their own actions contributed to the insanity.

- In August alone, the fund lost roughly 45 percent of its capital, an event that the fund’s risk analysis predicted should happen no more than once in the history of Western civilization. It shouldn’t be unduly difficult to draw a conclusion about whether LTCM was extremely unlucky, or whether its managers misunderstood the nature of the risk.

- Risks don’t disappear from markets or businesses; they are merely transferred or sold.

What I got out of it

- Good book about risk, reward, psychology of a successful investor