Disciples of the investing firm Berkshire Hathaway and its legendary leader, Warren Buffett, know that his mentors in investing were Benjamin Graham and Charlie Munger. But when Lawrence Cunningham, author of the recently-published Berkshire Beyond Buffett, asked the Berkshire CEO who should write the foreword, Buffett immediately suggested his friend of more than 40 years—Tom Murphy.

“Most of what I learned about management, I learned from Murph,” Buffett told Cunningham. “I kick myself, because I should have applied it much earlier.”

Along with Buffett himself, Murphy is one of eight CEOs praised in The Outsiders, a cult business classic beloved of investors like Bill Ackman, which attempts to define what differentiates a small number of leaders who massively outperform the market. Buffett is quoted in that book as saying that “Tom Murphy and [his long-time business partner] Dan Burke were probably the greatest two-person combination in management that the world has ever seen or maybe ever will see.”

Over about 40 years at the helm of their media conglomerate, Murphy and Burke developed a simple set of principles—decentralization, hiring the best possible people and giving them autonomy, and imposing rigorous cost controls—and took them to extremes. It’s not hard to see those principles at work at Berkshire, Cunningham says, where CEOs at the firm’s subsidiaries are given a lot of trust to execute and embody the company’s culture.

Buffett himself put a substantial amount of money and reputation behind the pair. He provided $550 million of the $3.2 billion with which Capital Cities, the firm Murphy and Burke ran, took over the much-larger ABC in 1985. It was his largest investment to date, and was the only thing that made the deal—at the time, the largest non-oil deal in history—possible.

This is the story of how Murphy developed his management credo and passed it on to the man typically lauded as the world’s greatest investor.

The making of a management philosophy

From Murphy’s foreword to Berkshire Beyond Buffett:

We are both proponents of a decentralized management philosophy: of hiring key people carefully; of pushing decisions down the organization; and of setting overall principles and resisting temptation to be involved with details. In other words, don’t hire a dog and try to do the barking.

It’s the kind of homespun wisdom you can easily imagine coming out of Buffett’s own mouth. The two men met in 1969 through a business-school classmate of Murphy’s, nearly 20 years before they had a formal business relationship. Capital Cities at the time was a growing but still modest-sized media company.

When Murphy had joined it in 1954 at the age of 29, it was just a local TV station that a friend of his father’s had bought out of bankruptcy. Both Murphy and Burke, whom Murphy hired in 1961, were relatively untested.Murphy had graduated from Harvard Business School’s legendary class of 1949; his classmates would later become CEOs of Xerox, Bloomingdale’s, General Dynamics, and Johnson and Johnson (the latter being Jim Burke, who introduced Murphy to his brother Dan). He had worked for a few years in advertising and product management. But neither he nor Burke had a broadcast background.

From the beginning, though, Murphy was cost-conscious. Asked to repaint the old convent building the station was housed in to appeal to advertisers, he painted just the two road-facing walls. He kept a picture of the station throughout his career.

The two men tried to hire the best possible people, and not too many of them, prioritizing “brains over experience;” TV wasn’t a high-tech business at the time. They gave young managers huge autonomy and gave them whole divisions to run once they showed promise. Burke and managers that followed him learned to stop sending weekly updates to headquarters because they wouldn’t get read. As long as stations were hitting their numbers and performed well over the long run, contact was limited.

Keeping control of costs, though, was essential, because revenue from TV stations is cyclical and lumpy, so low costs were the only way to consistently make money. In this effort, the budgeting process was ground zero. Burke and his CFO would go through operating budgets line by line with intense scrutiny on any capital expenditures, headcounts, and margins. Headquarters was run on a shoestring, with just 36 people when Capital Cities took over ABC. There was no PR department or mergers-and-acquisitions staff; Murphy’s personal secretary handled press calls rather than paying someone else to do it. All this meant that Murphy’s stations had the highest margins in the business, north of 50% compared to an average of 30%.

Murphy tried to get Buffett to be a director at Capital Cities shortly after they met; he went to Berkshire’s headquarters in Omaha, Nebraska, to try to convince him. Buffett declined because of the company’s high price-to-earnings multiple, but told Murphy to call any time he needed advice.

“From that day on, Warren was the best director I had even though, technically, he wasn’t directing,” Murphy said (pdf). He describes his many talks with Buffett over the years as “Acquisitions 101.”

A lesson in acquisitions

Even before Buffett and Murphy met, Capital Cities was highly acquisitive, going from a single TV station to owning several regional broadcasters and a couple of publishing firms by the time of their first encounter. But the biggest deals came afterwards.

Many acquisitions fail due to bad fit or underestimating the costs of integration. Murphy’s almost never did, which is all the remarkable considering he had no M&A specialists and didn’t use the high-priced Wall Street investment bankers and consultants that companies typically hire.

Instead, as Thorndike describes in detail in The Outsiders, Murphy never delegated the process to anyone, and used Buffett as a sounding board. He was willing to wait out an attractive deal, but also make big bets when he had conviction. He was often ready to move quickly when others might not because of his extreme confidence in Burke’s ability to quickly boost margins.

Murphy’s method of deal sourcing, meanwhile, involved staying out of the public eye, and spending years developing relationships with potential prospects. He never financed with equity, either generating cash internally, or using debt which was nearly always paid off within three years. All his major deals were through direct contact with sellers; they were never hostile, and never through an auction. He had strict return requirements: a double-digit after-tax return over 10 years, without leverage.

It’s not hard to see Buffett’s influence on Murphy’s dealmaking style. Buffett also famously avoids hostile deals and auctions, forms close relationships with the owners of family companies, and uses internally generated capital to finance deals.

He follows the same negotiating strategy, too, preferring to let a potential seller give his best price, making a quick counter-offer, and moving on if they don’t match. Murphy told Thorndike that when Buffett eventually decided to invest into the Capital Cities acquisition of ABC, it took the two men just 15 minutes to talk it through.

The master becomes the student

Yet though Murphy downplays it, Buffett also learned a lot from watching him build a diffuse conglomerate at a time when Berkshire was still taking partial stakes in companies rather than buying them outright. Buffett had sold off a few failing businesses in the mid-1980s, but swore never to do so again, focusing on providing permanent homes.

Cunningham interviewed a wide variety of Berkshire’s operating leaders for Berkshire Beyond Buffett, and found a number of common principles at the core of Berkshire’s management philosophy, notably budget-consciousness, hiring entrepreneurial self-starters, decentralization and autonomy, skilled acquisition, a sense of permanence, and a resolve to forgive mistakes but never tolerate moral failure. Though Buffett started his career with many of these ideas, and some were the result of his simple lack of experience, you can see him converge over time to the style outlined in Cunningham’s book.

“Tom was primarily a manager early in his career, an investor later,” Cunningham said. “Warren was primarily an investor for most of his career and a manager later.” He adds, ”I think they both shared that knowledge at the beginning of their careers and then learned from each other how valuable it is as they moved forward. Warren, early in his career, really did try to manage the companies in his conglomerate very closely. He’d try to recommend when to buy sugar and how much. He eventually realized that’s not a good idea. He’s not going to know the facts that his CEOs will know.”

Today, Buffett takes decentralization further still than Murphy did. He has an even tinier headquarters staff, and declines to hold annual budget meetings.

The big deal

The relationship hit perhaps its most critical juncture with the takeover of ABC. The size of Buffett’s investment alone made it an act of faith in Murphy. And after the purchase, ABC became the ultimate application of the Murphy and Burke formula of cost-cutting. According to The Outsiders, they got rid of 1,500 staff, the executive elevator, and the private dining room, and sold the company’s midtown Manhattan headquarters for $175 million.

The margin gap between former ABC and Capital Cities stations closed within two years. The network surpassed rivals CBS and NBC in profitability. It also went from last place to first in the ratings: Even though the company was obsessively lean elsewhere, it tended to invest heavily in news budgets and technology. This wasn’t out of an altruistic fondness for good journalism, but simply because, in media, the leaders in any local market got a disproportionate share of the ad revenue.

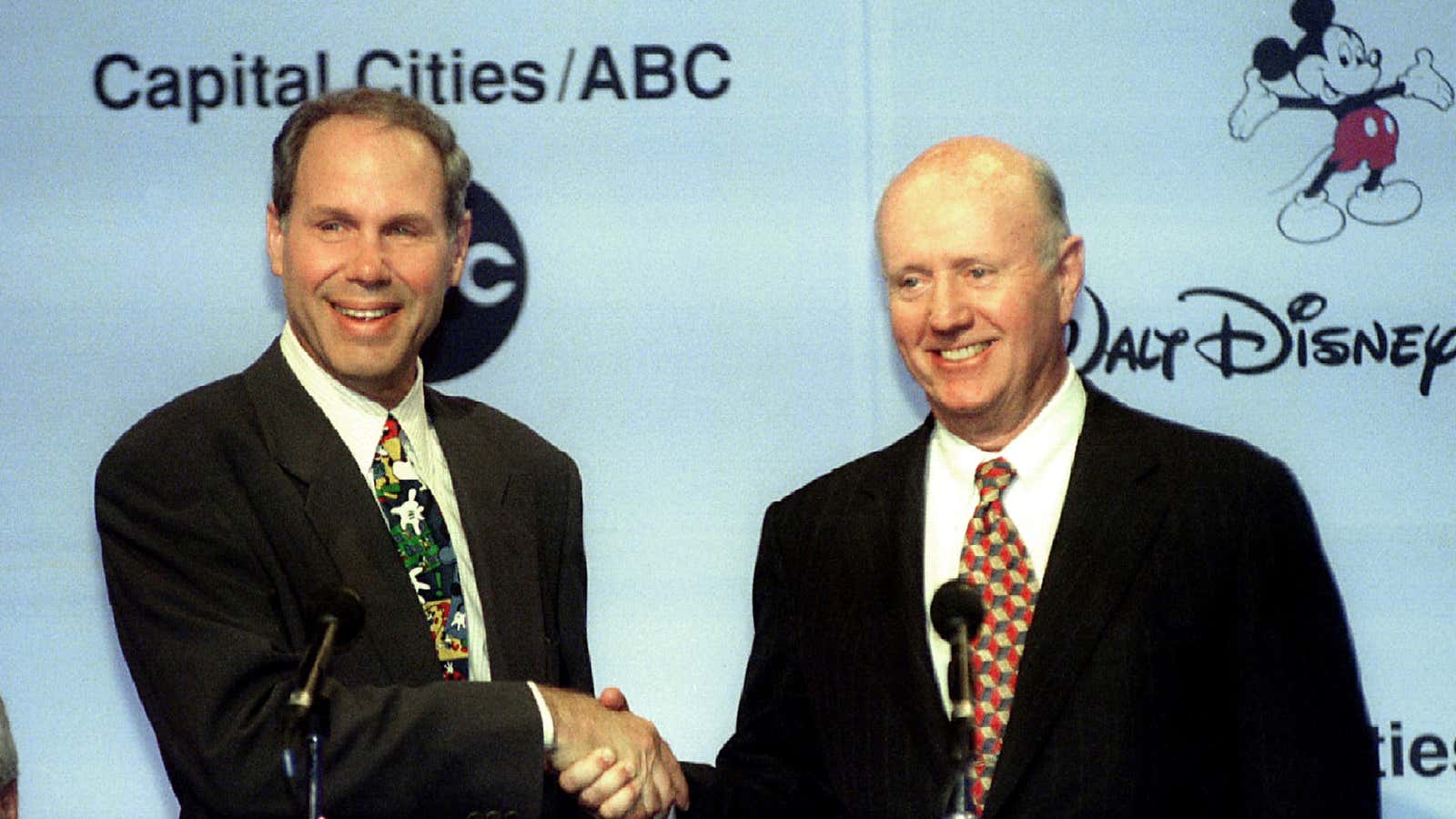

The successful merger with ABC, Murphy’s last major purchase, made the company all the more profitable and attractive. With Burke retired and Murphy hitting 70, the idea of a final deal made sense. In 1995, he negotiated Capital Cities/ABC’s acquisition by the Walt Disney company.

Buffett didn’t fund the deal, but he did kick it off by suggesting that Murphy sit down with Disney’s then-CEO, Michael Eisner, at the legendary Sun Valley Conference. Eventually, they negotiated a $19 billion purchase—at the time, the second-largest deal in history.

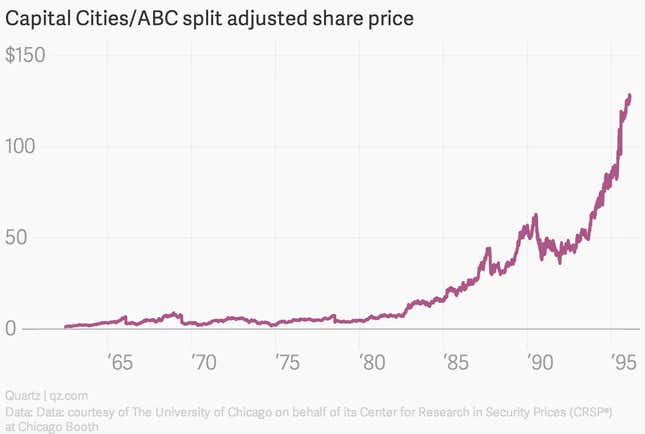

It was the cap to a remarkable career for Murphy. He estimates that a shareholder who bought in when Capital Cities went public in the late 1950s would have made a 2000-to-1 return at its exit. The acquisition turned out great for Disney too: It included an 80% stake in ESPN, then losing $40 million a year, and now valued at around $80 billion.

Murphy remained a Disney board member for years after selling Capital Cities/ABC. He still serves on Berkshire’s board, and showed some internet bona fides as a director of Doubleclick, an internet advertising firm that sold to Google for $3.1 billion.

At the end of the day, his advice to young people in an interview with Harvard Business School is something you might hear from any Silicon Valley entrepreneur: Don’t fear failure. If you try, and it doesn’t work, at least you “weren’t working for General Electric or some big company where all the finances were taken care of and all of the things were being done for you,” he said. ”The rewards of being your own boss are wonderful.”